December 26, 1519 – February 3, 1520

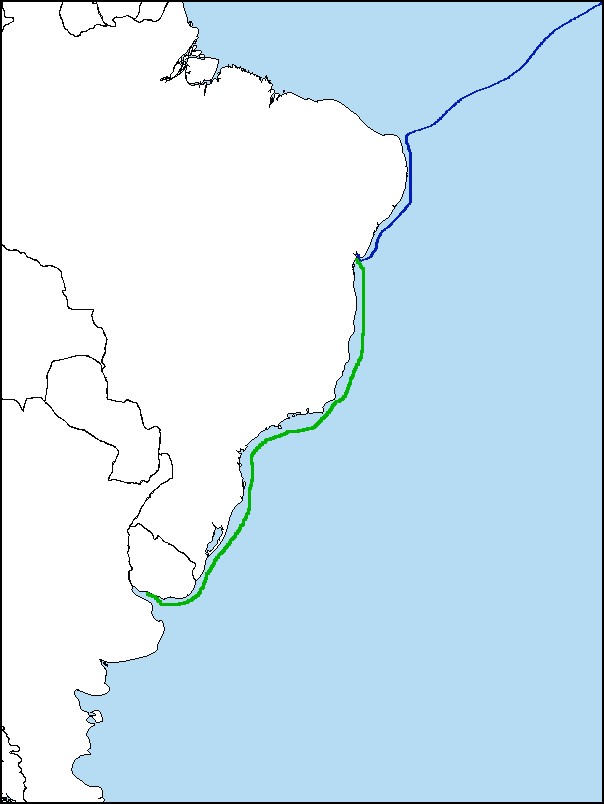

Out of Rio de Janeiro, Magellan’s fleet sailed southward, hugging the coast of South America more tightly than ever under winds that now blew far more favorably for its preferred course than they had before the sojourn in Eden. Its next intended destination was an infamous place in some ways, but one that also stood as the captain general’s fondest hope for a way to get to the other side of South America without having to sail all the way around it.

The place in question was then commonly known as the Mar Dulce, or the “Freshwater Sea.” We know it today as the Río de la Plata, or “Silver River,” home to the bustling port-city capitals of not one but two countries: Uruguay’s capital of Montevideo lies on its north shore, while Argentina’s capital of Buenos Aires lies on its southern banks. The body of water was given its modern name a decade and a half after Magellan’s voyage by the Venetian explorer Sebastian Cabot, who, like Magellan, visited it whilst sailing under the flag of Spain. The designation he chose was every bit as much of a misnomer as Rio de Janeiro to the north. It derived from Cabot’s fond imagining that this part of South America would prove a fountain of yet more New World silver, the same stuff that had already made Spain the wealthiest country in the world by that point. In the end, though, the region would show itself not to be particularly rich in that precious resource. Meanwhile, if the Río de la Plata is a river, it is the most oddly shaped example of its breed in the world, being fully 140 miles (220 kilometers) wide at its broadest point where it empties into the Atlantic Ocean, set against a total length of just 180 miles (290 kilometers). It’s probably better described as an estuary, or, better yet, as simply a bay.

All of which is to say that the appellation of Mar Dulce by which Magellan knew it was a more accurate term for this body of water on the whole than the one by which we know it. For all that calling it a full-fledged sea is perhaps being rather generous, its salt content really was, if not quite zero, at least far less than that of the bordering ocean during Magellan’s time, thanks to the freshwater that flowed into it from the Paraná River, the Uruguay River, and many other, smaller inland waterways. This freshwater tended to park itself atop the salinated liquid from the ocean, making much of the bay’s surface a perfectly serviceable source of drinking water.

The Mar Dulce was first discovered just seven years before Magellan’s expedition left Spain, by a pair of Portuguese caravels poking around in places where they really oughtn’t to have been according to the treaty signed between Spain and Portugal with regard to who owned what in the Americas. His trespasser status notwithstanding, the Portuguese captain João de Lisboa reported the beginning of a waterway that, so he claimed, stretched deep into the interior of the continent, quite possibly all the way through from east to west.

After duly scolding King Manual of Portugal for violating the terms of their two country’s agreement, King Ferdinand of Spain ordered an expedition by his own navy to the Mar Dulce shortly before his death. Juan Díaz de Solís reached its mouth in January of 1516 with three small ships and 70 men. Before he could properly investigate Lisboa’s claims as to the waterway’s inland extent, however, he suffered a grisly fate.

Spotting a tribe of natives on the shore, Solís and ten or so of his men piled into a longboat to greet them without a second thought. After all, virtually all of the natives the Spanish and Portuguese had met on the east coast of South America to date had been overawed by their foreign visitors. Why should these ones be any different?

But, sadly for Solís and his men, these ones were different. Very different. Lurid reports that would soon spread widely back in Europe told how the rest of the Spanish sailors looked on in horror from their ships while the natives picked up clubs and bashed the landing party to death without giving them the chance to say a word. Then the real horrors began, as the natives proceeded to cut the bodies to pieces, throw them onto their cooking fires, and eat them, all of this brutality likewise taking place in full view of the ships standing offshore. Deciding that prudence was the better part of valor, those men who had remained with the ships raised their sails and hightailed it out of there before night fell, having no wish to face an ambush from these people who had made it so abundantly clear that they, for one, did not wish to be friends. No European returned to the Mar Dulce in the four years that followed.

Now, though, Magellan was about to do just that, in order to find out once and for all whether João de Lisboa’s theory that it could represent a route all the way to the Pacific Ocean was correct. Although his officers and crew were understandably unnerved by the prospect of visiting this region of purportedly savage cannibals, they were also excited about what they saw as an approaching moment of truth for the expedition as a whole. If Lisboa proved trustworthy, success might shortly be theirs, and with it untold riches.

They were now leaving the relatively known parts of the New World behind, sailing into waters that only a handful of intrepid explorers had traversed before them. The days grew longer and longer as the ships glided southward at a healthy clip. The short nights were a relief in a way, given that, even for the most seasoned sailors — indeed, perhaps especially for them — the sight of the night sky in these antipodean climes was an unnerving one. The constellations they had known all their lives were gone — even Ursa Major, that Great Bear of the heavens, who, as Homer had sung, “alone is denied a plunge in the ocean’s baths.” By way of compensation, the magnificent Southern Cross, which Homer had known but which had been lost to and forgotten by more recent generations of Europeans due to the inexorable precession of the equinoxes, now shined down on the transplanted Northerners in its full splendor once again.

Two and a half weeks at sea went by, during which 1519 passed into 1520. What with the ever-mercurial wind deigning to serve as an ally rather than an enemy during this stage of the voyage, the ships made excellent progress. On January 13, they spotted the wide opening in the coastline that they sought, the most inviting of its kind they had seen since Rio de Janeiro, but at the same time dwarfing that little bay in size. The fleet nudged inside, dropping anchor at sunset amidst palpable excitement. Some of the men lowered buckets into the water. When they pulled them back up, they learned that the name of the Mar Dulce was not a misnomer; the buckets were filled with cool, clear freshwater rather than saltwater. This was a welcome luxury, giving the men something to drink that wasn’t brackish like the liquids carried in barrels in the ships’ holds, giving them something to wash with that didn’t chafe the skin, burn the eyes and nostrils, and leave hair and clothing stiff as boards. Nevertheless, all of the experienced seamen, Magellan among them, would have much preferred to discover that the stories of a freshwater bay were not true. For they understood that it boded ill for their hopes that the bay was really a strait that cut all the way through the continent from one side to the other.

Still, there was only one way to definitively prove or disprove that assertion. The next morning, the ships dispersed to commence a slow, methodical survey of the Mar Dulce, the first that had ever been conducted. Each night,they were careful to drop anchor well out toward the center of the bay, leaving an armed watch on deck throughout the hours of darkness. Nobody knew much of anything about the mysterious cannibals of the Mar Dulce, didn’t know whether they could build and pilot canoes like those of the Tupi. But, given what what had happened to Solís, no one wanted to take any chances either.

Within eight days, the survey was completed, yielding the hugely disappointing conclusion that the Mar Dulce was no strait; Magellan’s countryman Lisboa had let him down, as so many other Portuguese had done in recent years. The only remaining shred of hope lay in the two large rivers which fed into the bay. Determined to leave no possibility untested, Magellan decided to send a single ship to explore them, to find out if maybe, just maybe, one of them showed signs of being a navigable transcontinental waterway in its own right. He chose for the task the Santiago, whose small size and the shallow draft that went along with it were a virtue when it came to this mission. Additionally, Captain Juan Rodríguez Serrano of the Santiago was the only one of his captains whom Magellan was prepared to trust with such a tricky bit of sailing, being not coincidentally the only one who was a professional seaman rather than a political appointee.

So, the crew of the Santiago waved goodbye to their comrades and set off up the river we now know as the Paraná, the second longest in all of South America. Like a mountain climber on perilous terrain, the ship couldn’t afford to put a single foot wrong. The crew took soundings again and again, looking for the hidden shoals that could leave them grounded and helpless in the middle of a hostile jungle. When the sailors had a moment to look up, they peered into the thick foliage on each side of them and wondered whether it concealed a cannibal war party that was about to overwhelm them. The once-terrifying barrenness of the open ocean now seemed a vision of safety.

When the river took a turn toward the north — i.e., away from the direction it needed to travel in order to cross the continent — Serrano decided enough was enough. He turned the Santiago around — a delicate operation in itself — and let the current carry it back down to the Mar Dulce. But his work wasn’t finished. Hardly had the Santiago rejoined the fleet than Magellan sent it off again, to explore the second great river feeding into the bay, the one we know as the Uruguay River. This one looked less promising from the start, given that it flowed into the bay from the north rather than the west, and it showed no sign of changing its direction when the Santiago began to probe its length. After a few days, Serrano turned his ship around, to report back to his captain general that the expedition’s best hope had failed it; there was no highway between oceans to be found here. On the plus side, the Santiago had not encountered a single human being upriver, hostile or otherwise.

The rest of the fleet could not say the same. Not long after watching the Santiago depart on the first of its upriver journeys, a lookout with the ships that remained behind shouted that there were people milling around on the nearest shore. Sure enough, natives could be seen there, looking much the same in their dress — or rather lack thereof — as the Tupi. Be that as it may, no one wanted to repeat the mistake of the overly trusting and so now dearly departed Juan Díaz de Solís. Magellan elected to wait the situation out, to let the natives make the first move, if there was to be one.

At dusk, a lone hulking giant emerged from the treeline, dragging a small one-man canoe behind him. He climbed in, shoved off, and rowed with confident, powerful strokes right up to the ships. He flitted around and between the vessels, shouting up at the sailors the whole while in a voice like the bellowing of a bull; whether it was a form of greeting, a challenge, or a full-on war cry, no one knew. For his part, he clearly had no idea of the purpose of the dozens of muskets that were trained on him from above, their owners under strict orders from Magellan not to shoot unless the giant did something obviously threatening. At length, he seemed to tire of the game, and rowed back to shore. The sailors waited all night for the attack of which the giant might have been the herald, but it never came.

In the morning, Magellan concluded that he needed to force the issue, one way or the other. He gathered fully half of the sailors aboard longboats and launches, arming them with most of the fleet’s personal weaponry. With the cannons of the Trinidad aimed at the shore where the natives congregated, ready to provide artillery support if necessary, the landing party set off. Rather than talking or fighting, the natives simply melted away into the jungle as the boats approached them.

The sailors set up a tight defensive beachhead, inside of which they hunted for small game and gathered fruits and berries, both to eat now and to carry back aboard the ships to ward off the pangs of scurvy in future days. All the while, they could hear the natives scurrying about and muttering to one another just beyond the perimeter line. Needless to say, tensions ran high among the landing party. Yet the natives never emerged into the open again over the course of the week and more that the sailors stayed ashore.

With, that is, just one exception. One evening another giant — or perhaps the same one; it was hard to tell — materialized from another part of the jungle to paddle out to the fleet. Seeming to recognize the seat of power by instinct, he came up to the Trinidad and shouted and gestured whilst standing up in his boat, indicating that he wished to come aboard. Using gestures of his own, Magellan bid him welcome to do so. With no further ado, the giant climbed up the hull of the vessel as adroitly as the Tupi women once had done and raised himself proudly to his full height there on the deck, glowering down at the captain general, the crown of whose head barely reached to the giant’s chest. Unfazed, Magellan offered him a shirt of bright red cloth, which he appeared to like very much. Then, remembering how beguiled the Tupi had been by the simplest objects made of metal, Magellan showed him bells and scissors and other trinkets of that nature. This native, however, seemed thoroughly unimpressed by such baubles. Clutching the shirt in one immense hand, he abruptly climbed back over the gunwale and sprang easily back into his canoe. Then he rowed away into the gloaming of the encroaching subtropical night, never to be seen again. Magellan and his men waited for the same or another diplomat to arrive to resume negotiations over the days that followed, but no other canoes ever approached the ships.

Thus these natives were fated to remain an enigma from first to last. They were most likely the Querandí, an exceptionally warlike group who would give the Spaniards who arrived to colonize the shores of the Mar Dulce in the decades to come everything they could handle and then some. Magellan was lucky. While he did lose two sailors in the bay, neither of these deaths had anything to do with the people who lived there. One man from the Concepción somehow managed to fall overboard in the still waters of the bay, while one from the San Antonio received a fatal kick in a wild shipboard brawl that was perchance a byproduct of the tense situation.

Their captain general not being much in the habit of sharing his thoughts and plans, many among the crew and even the officers believed that they must be going home when the fleet left the Mar Dulce on the morning of February 3, 1520. This was not an illogical assumption to make, based on the information available to them. They had come to South America, they had tried to find a passage through the continent in what looked to be the most promising place, and they had come up empty. What else was there left to do? Already they were at approximately the same latitude as the southern tip of Africa, throwing the real utility of any westward route to Asia they might still discover by sailing yet further south into serious question.

Magellan, however, was anything but a quitter. He had told King Charles that he would sail west to Asia, and, by God, he would do so, even if the trail he blazed proved to be worth nothing in the economic reckoning of empire. Far from coming to an end with the extinguishing of its best hope to pay off as a commercial proposition, the fleet’s journey of pure discovery was just beginning.

Did you enjoy this chapter? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Leo Vellès

Another great chapter Jimmy, and by now the expedition reached the coast of my home country of Argentina. About that, I don`t think the tribe that killed Juan Díaz de Solís and his crew were the Guaraní, which are more common in what is now the north of Argentina and Paraguay. Most probably, they were the Charrúas, that lived in what today is Uruguay. And I never heard that any of those two tribes practiced cannibalism. It seems it was likely an “urban legend” from the times before this region was urbanized.

Jimmy Maher

I think it’s fairly well-accepted that the Guaraní practiced a ritual form of cannibalism. This academic article, for example, takes it as a given: https://leiaufsc.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/fausto-2007.pdf.

That said, the Querandí, who caused the Spaniards no end of trouble later on, may be the best candidates of all. I’ve changed the text to reflect this. Thanks for causing me to give it another look!

By the way, what is the water like in the Río de la Plata today? Is it still drinkable at the surface, or is salty now, or is it just too polluted? I couldn’t find a definitive answer on this in English-language sources, which is why I kind of hedged my bets above.

Leo Vellés

I dug a little deeper and yes, it is true what you say that the Guaraní practiced a ritual form of cannibalism, but it is also true that the Charruas were most probably the tribe that attacked them. About what you ask, I believe that there is not one Porteño (the citizens of Buenos Aires) that conceive to drink from that water, but maybe that is not the same for the Montevideans. You see, the Buenos Aires side of the Río de la Plata is very polluted, maybe a reason is that Buenos Aires is a very big city. Until the first decades of the 20th century it was common to take a bath in that waters, specially in an área called La Costanera, in the southern part of the city, but today it is forbidden by the authorities to take baths there, let alone drink from that waters. In Montevideo the story is very different, I once cross the city coast on a trip and I was amazed to see people going to some nice beaches to spend a nice day by the river, even taking baths. I don´t know if that side of the coast is less polluted than the argentinian because Montevideo is a way smaller and less populated city, but i will tell you that from the Porteño point of view, I am a little jelaous of the Uruguay´s side of the Río de la Plata.

Tom Chambers

Fascinating story, thanks!

“The fleet nudged inside, weighing anchor at sunset…” If I am guessing your intended meaning correctly, then this should be “dropping anchor.” Weighing anchor is the opposite.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!