“Unity succeeds division and division follows unity. One is bound to be replaced by the other after a long span of time. This is the way with things in the world.”

Thus begins Luo Guanzhong’s fourteenth-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which many Chinese regard as the most monumental work of literature their culture has ever produced. Certainly these opening lines describe a profoundly Chinese view of history, one thoroughly at odds with our Western obsession with progress narratives: history as a wheel rather than an arrow, an eternal recurrence of unity yielding to discord, good times yielding to bad, and then vice versa.

But for the Westerner trying to make sense of China’s past — the past of one of the oldest continuous civilizations and the single oldest centralized state in the world — the words carry a different, more ironic sort of resonance. “History is just one damned thing after another,” runs a timeless piece of American folk wisdom, inadvertently echoing Luo Guanzhong’s more rarefied philosophy. Both assertions ring dismayingly true for the Westerner trying to get a handle on Chinese history, who is confronted with an endless, bewildering succession of dynasties, emperors, wars, and battles, all arriving complete with monosyllabic, unpronounceable names that seem impossible to hold distinct from one another. Chinese history becomes a timeline of obscure data points without any overarching sense or thrust.

The central problem, of course, is a near total lack of context. For most Westerners, not only the history but the language and geography of China — these three things being intimately bound together there, as they are everywhere — are so utterly foreign that they might just as well be those of a race of aliens living on another planet. When we of the West read about the details of Western history, on the other hand, we have an overarching wide-angle narrative arc to slot them into, along with a wealth of sometimes unconscious shared cultural understanding. We lack all of those things when it comes to China. Small wonder that the Chinese have so often been called inscrutable, impenetrable, unknowable by Western observers. What with their propensity for building walls both physical and metaphorical to keep the outside world outside, the sense of alienness which clings to their culture makes any sense of understanding difficult to achieve.

How might I overcome some of these challenges? Let me begin by giving you a little primer on China and the Chinese that will make them slightly less alien from the outset, before we embark upon our journey through their long history in the chapters to come. If nothing else, I need to make one thing abundantly clear: that to talk of just one uniform China, monolithic in its contented inscrutability, is to misunderstand the real nature of the place entirely. Much of our confusion tends to stem from our desire to see China as all one thing.

The reality is that modern China is a hugely variegated behemoth that sprawls over an enormous swath of eastern Asia. It is 3.6 million square miles (9.3 million square kilometers) in extent, making it the fourth largest country in the world in terms of real estate in addition to being the most populous of them all. Its land borders touch those of fourteen other countries, for all of whom its presence is an enormously consequential fact of everyday life, while the 8700 miles (14,000 kilometers) of coastline that represent its southeastern and eastern borders touch three separate seas, with similarly immense geopolitical consequences.

Within its vast territory can be found almost every imaginable type of terrestrial climate, from subtropical in the extreme south to subarctic in the extreme north. China’s topography is equally varied. It contains Mount Everest, the highest point in the world; it also contains the sunken bed of the former Lake Ayding, the second lowest piece of dry land in the world. It encompasses broiling deserts, fetid swamps, soaring mountains, rolling hills, virgin forests, dusty steppes, grassy plains, and fertile river valleys. If a form of landscape exists somewhere on earth, it probably exists somewhere in China.

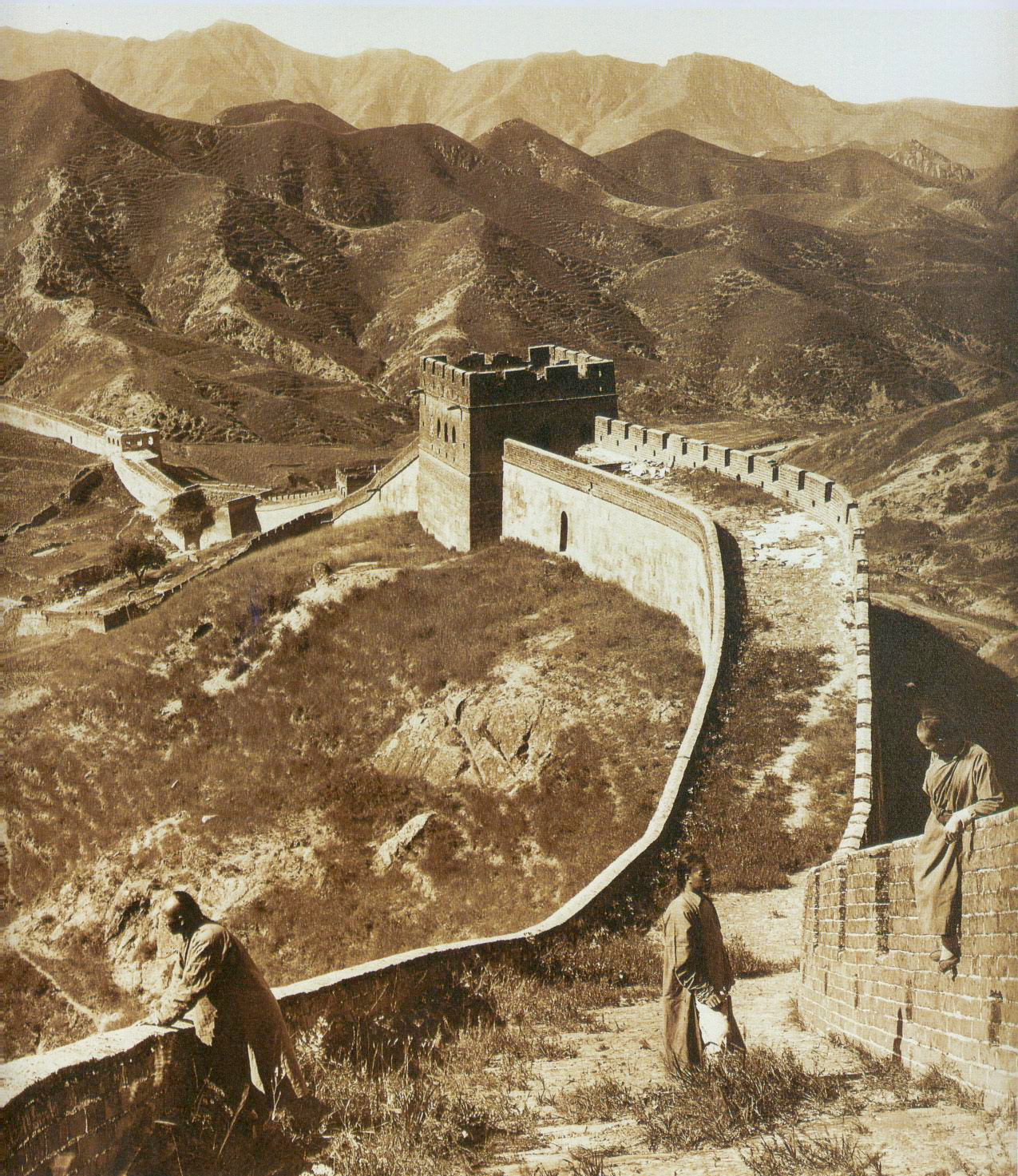

We clearly need to bring some order to the sprawl of China if we are to have any hope of understanding it. We might begin by noting that the China of today is actually much larger in terms of geography than it has been for the majority of its history. The Great Wall provides a telling testament to this reality. When it was built hundreds of years ago, it ran along the frontiers of Ming China; today, the most commonly visited section of it just north of Beijing is some 700 miles (1100 kilometers) south of the country’s northern border.

We can usefully divide modern China into two, using the general course of the old frontier walls as our line of demarcation. That territory outside the walls, encompassing fully half of the area of the present-day country, we shall call Outer China. With the partial exception only of the region known as Manchuria to the northeast of Beijing, it is and has long been an inhospitable place for humans to settle in. The Tibetan Plateau of western Outer China and the Gobi Desert of northern Outer China are arid regions marked by extremes of heat and cold, devoid of rivers, that lifeblood of sedentary agriculture and thus by extension of civilization. Most of these regions through most of history were not considered a part of China.

During those times when they were not, they were the lands of the “barbarians”: the nomadic horsemen and herders who have always been indelibly linked to the steppes of inland Asia in the world’s imagination. For example, the fearsome Genghis Khan, one of the vanishingly few figures who are equally prominent in the pre-modern histories of both the West and the East, sprang from this milieu. Even in the time of George Macartney, Westerners were still content to refer to all of this largely unmapped territory under the blanket name of “Tartary” — a term not that far removed from “Here Be Dragons.” The hardy people who live there today no longer terrorize the lands which border theirs, but some of them still keep to the old ways in other respects, roaming from place to place with their herds, sleeping in their yurts, speaking the old languages, singing the old songs, and dancing the old dances. All the wonders of modern technology cannot turn Outer China into a place conducive to large populations; fewer than ten percent of China’s people live there today.

That leaves us with Inner China: the densely populated heartland, which is home as of this writing to a staggering 1.35 billion souls, or 17 percent of the whole world’s people — four times more than any other nation, excepting only China’s neighbor India. It is capable of supporting such a huge population thanks to the great Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, respectively the sixth and third longest in the world, which bring their precious loads of water and nutrients down from the highlands that mark the edge of the Tibetan Plateau to the west. Throughout most of recorded history, Inner China was the only China. It is still sometimes referred to as “China Proper” — or, even more dismissively of the Chinese territory which surrounds it, as the “real” China.

Yet the people who lived in Inner China in olden times were seldom in a position to dismiss those living outside their walls. As the very presence of those walls attests, most of recorded Chinese history is marked by the tension between the nomads of the steppes and the settled farmers of Inner China, notwithstanding the enormous population disparity between the two regions. For only sporadically during its history has China been a formidable military power with the wherewithal to go toe to toe with the barbarians. Its greatest strength has been what we might call today its “soft power”: the power of its culture, which until relatively recently was much more advanced than that of any of the lands close to it.

Instead of marshaling armies to march forth and defeat the barbarians at their gates in battle, the Chinese emperors generally preferred to hunker down behind walls and a variety of diplomatic accommodations that, once all of the niceties of courtly ceremony were set aside, often amounted to little more than paying the steppe dwellers an annual ransom not to attack. Nevertheless, attack they sometimes did, and sometimes even succeeded in overthrowing the current dynasty and taking over. But when they did so, there invariably followed the ultimate testament to Chinese soft power: rather than bending China to their ways, the barbarians soon became Chinese themselves, and life inside the Middle Kingdom continued more or less as usual. The Qing dynasty that George Macartney encountered, for example, had begun with the capture of Beijing by a barbarian army which swept down out of Manchuria in 1644. And yet the land which greeted Macartney 150 years later was thoroughly, indubitably Chinese. It is thanks to this odd facility for cultural absorption — its final, best gambit when all of its walls and all of its ransom payments have failed it — that China has been able to persist as a coherent, self-standing entity in the world for so long.

But even Inner China is far from a culturally homogeneous place. It too can be divided into two regions: the North and the South, separated by the Qinling Mountain Range which runs from west to east through the middle of it. The personalities of the two regions are to a large degree dictated by that of the river which flows through each of them.

The North is the land of the Yellow River, which gets its name from the unusual shade of its water, the result of the powdery yellow dust with which it is saturated, known as “loess” in the West after a similar soil found in the Rhineland of Germany. The river carries this loess down from the western highlands and deposits it along its flood plain. The Yellow River is vital to life in Northern Inner China, but it is also cantankerous and dangerous, such that it has earned the appellation of “China’s Sorrow.” For the enormous quantities of silt it carries — making up at times almost half of its total weight, a proportion larger than that of any other river in the world — is constantly altering the landscape around it and causing the river to change its course. Already during ancient times, the Chinese made herculean efforts to tame the Yellow River, building dikes to a height of 40 feet (12 meters) or more in places. But it was always to no avail in the end; the river must eventually break through its restraints and adopt a new course, usually at tragic cost in lives and property.

By way of compensation, the alluvium the river leaves behind is very fecund indeed. Although the climate of the North is fairly dry, this fertile soil, combined with the vast flat plains that dominate the landscape, make it a region well suited to the cultivation of wheat and millet among other crops — but not, many Westerners are surprised to learn, rice: the traditional diet of the North is rather marked by noodles and breads.

The South is the land of the Yangtze River, which is a very different, more placid waterway than the Yellow, even as it carries a greater total volume of water. As it flows toward the ocean, the lazy, good-natured Yangtze branches into countless smaller and smaller tributaries, like capillaries in a map of the human circulatory system.

The South as a whole is a wetter, warmer place than the North — so warm that it’s often possible to grow food there during the winter months. Its terrain is speckled with lakes, streams, and canals, while the steamy land in between is covered with lush forests and thick vegetation, shading into outright jungle as you near the southwestern border. The soil here is even more fertile than in the North, yielding rich crops of tea, cotton, citrus fruits, and, most of all, of rice. The staple of the Southern diet, rice boasts a caloric and nutritional content by weight that is considerably higher than that of the wheat and millet of the North. Thanks to the supremely bountiful land in which they are privileged to live, the people of the South have historically been plumper, healthier, richer, and more numerous than those of the North.

Based on all of these factors, one might expect the South to be the politically dominant region of China as well, but such is not in fact the case. Chinese civilization as we know it today began in the North and spread to the South, and China has been ruled from the North over the majority of the time it has been a united land; this is still true today, of course, given the nation’s modern capital of Beijing. Historians in China and elsewhere have been debating for generations just why the economic supremacy of the South never resulted in political hegemony.

One persuasive answer is to be found in an old Chinese saying: “In the North the horse, in the South the boat.” The open plains of the North were conducive to swift travel and communication on horseback; this made the North from an early date a more structured, unified sort of place, with a more cohesive identity. Traversing the South, by contrast, was a much more arduous process that required one to reckon with body of water after body of water; this presented an enormous challenge to the development of all but the most localized forms of administration and cooperation. In addition, the open terrain of the North was more vulnerable to incursions by the dreaded barbarians of the steppes, while the South was somewhat protected from attack by its terrain that was so unwelcoming to riders. Necessity being the mother of invention, the North’s very vulnerability may have led it to develop the institutions of government that it judged to be necessary for protecting itself — not least among them the building of walls. The temperamental Yellow River also created a demand for shared, coordinated efforts, in the shape of irrigation and flood control. And those institutional, bureaucratic attitudes, once inculcated, continued to grow and entrench themselves ever more deeply in the social fabric of the North. Its people became natural organizers in a way that the people of the South never did.

Some have speculated that having a political center of gravity in the one region and an economic center of gravity in the other may have done wonders for China’s long-term stability, might be one of the principal reasons such a large piece of land has been able to persist as a single political entity for so long. Still, the cultural contrasts between North and South do create some inevitable tensions. Northerners sometimes call Southerners “monkeys,” a reference not only to their slightly smaller average stature but to their alleged excitability and tendency to rush willy-nilly after the proverbial shiny object, whether it takes the form of a chance to get rich or a new social philosophy. Southerners call Northerners “steamed bread,” a reference to their supposedly deadly boring sobriety, conservatism, and constancy. It does seem reasonable to assert that the South has generally been more individualistic and acquisitive than the North throughout history, as well as less analytic; it is still today possessed of affinities for earth magic, geomancy, and landscape poetry that are lost on the typical stolid Northerner. Yet it’s also important not to exaggerate the differences or the tensions they create: certainly most native-born Northerners and Southerners alike consider both themselves and their counterparts on the other side of the Qinling Mountains to be what’s known as Han Chinese — i.e., members of the country’s dominant socio-ethnic group, the embodiment of its traditional culture.

The question of whether all of these Han Chinese speak the same language — and thus whether “Chinese” should be considered a singular language unto itself — is a weirdly convoluted one to answer. In the North, matters are actually simple enough. While there are dialects there, all are relatively small variations on Mandarin, the speech of Beijing, so named because it is historically associated with the mandarins, or bureaucrats, of imperial China. The people who live in the extreme west of the North have no significant difficulty understanding those who live in the extreme east. In the South, however, the story is very different. The dozens of “dialects” found there can in many cases be considered completely separate languages, if one’s criterion for defining such things is mutual intelligibility — or rather the lack thereof. Many people living in the rural South cannot understand the speech of other Southerners living just 100 miles (160 kilometers) away, much less that of the people of the North.

Linguists and historians have long speculated as to why the two regions should be so different in this respect. The most likely explanation is once again rooted in the ease of travel on the plains of the North, which brought its farms and villages into more frequent contact with one another. And to this should be added the stronger institutions of the North, which demanded a shared language for their shared projects. Unity of speech and unity of purpose thus became a virtuous, self-reinforcing circle in the North. But none of that occurred in the South.

The debate over whether Inner China as a whole is a land of one or many languages ironically serves to illustrate what an artificial construct the very idea of discrete languages actually is. All over the world, language has historically been a matter of continuums rather than hard-and-fast categories. In his survey of the language of China, linguist S. Robert Ramsey draws a parallel with the way that French transitions into Italian in the border regions of those two countries.

French is not sharply separated from Italian, but rather changes into its sister language gradually, from village to village across the French-Italian border. Its peripheral dialects merge into those of Italian. The people living in one French village can talk to their neighbors in the next village to the southeast, and they to those in the next, and so on, so that the chain of intelligibility continues unbroken into Italy. Peking [Beijing] Mandarin is linked to Shanghainese with about the same degree of complexity. From a linguistic point of view, the Chinese “dialects” could be considered different languages, just as French and Italian are.

Our rule of mutual intelligibility as the defining distinction between languages and dialects, which seems so straightforward and commonsensical on the surface, proves profoundly inadequate in situations like these. In many parts of Southern Inner China, as around the French-Italian border, there may exist a village whose inhabitants can understand and be understood by the people of each of the villages to either side of them, even as the latter two villages are unable to converse directly with one another. What happens to our neat rule in a case like this one?

Still, the leaders of modern China are very wedded to the notion of a single Chinese language, and have put a great deal of effort into making that an everyday reality. Most higher education, even in the South, now takes place using the Mandarin dialect of the North, and almost all organs of the state-run mass media broadcast exclusively in Mandarin. These efforts have borne fruit: most reasonably educated Southern Chinese under a certain age can understand Mandarin easily enough, even if they don’t speak it much in their daily lives.

But the most cogent argument for Chinese as a single language rather than a family of them is its written form. For written Chinese is indeed written Chinese, full stop. China was the very first literate civilization to emerge east of Mesopotamia, and that literacy was the key to administering its babble of tongues for the more than 3000 years of its history that preceded the invention of electronic mass media. Simply put, those officials and bureaucrats who couldn’t talk to one another could still write to one another. This ability came down to the nature of written Chinese: unlike the phonetic systems of writing of the West, whose glyphs each express a granular unit of sound in the spoken language, the Chinese glyphs are ideographic, meaning that they express self-contained things, actions, or concepts, and carry no clue on the page as to their pronunciation in the spoken language. Thus a Northerner and a Southerner might “hear” the same text very differently in their heads, but both can understand it equally well. In more recent times, written Chinese has supplemented its ideograms with glyphs which to some extent do represent the sound of spoken Mandarin, a necessary coping mechanism in a fast-moving modern world. Still, at its core Chinese writing remains conceptually strange to anyone raised on a Western alphabet.

In fact, many Westerners find the Chinese language to be the most daunting barrier of all standing between them and a better understanding of China in general. It seems almost defiantly inscrutable, begrudging us even the smallest of shared frames of reference. Not only does it share no words with our languages, but it lacks even the concept of words: “The Chinese have no everyday word for ‘word,'” notes S. Robert Ramsey a little cheekily. Chinese is rather a monosyllabic language whose syllables are its basic units of meaning, grouped together to form sentences of more complex meaning without feeling any need of those intermediate entities we call words. Reading it fluently requires knowing the meaning of some 5000 separate glyphs, a marked contrast to the 26 letters of our Latin alphabet. And yet its grammar is as simple as its system of glyphs is complex — so simple as to be almost nonexistent, lacking such basic Western niceties as tense, case, conjugation, and inflection, leaving the Western student to wonder how it is possible to express any real nuance at all using it. Indeed, for a long time Western linguists were in the habit of calling Chinese “a lower form of language,” one that had wandered into an evolutionary cul de sac at some point in the distant past and been trapped there ever since. Even many Chinese intellectuals of the early twentieth century — a period of widespread soul-searching in the face of a modern world that seemed to have passed their country by — blamed their language for a multitude of woes. Could it be that its “lack of the ability to consider objective, neutral matter [is] the real explanation of the failure on the part of the Chinese to develop a system of natural science?” wondered the Chinese-American linguist Yuen Ren Chao.

But Western diplomats who have tried to learn and use this purportedly simplistic, stunted language have found that its subtleties are nearly infinite, such that they are constantly saying the wrong things, thereby insulting over and over again the Chinese dignitaries they are earnestly attempting to flatter. Setting aside the vagaries of idiom and culture, the most challenging aspect of spoken Chinese from a purely technical perspective is undoubtedly its use of “tones,” or changes in pitch that convey meaning: the syllable ma, for example, can mean “mother,” “hemp,” “horse”, or “to scold,” depending on whether it is pronounced with a high and level tone, a high and rising tone, a low and level tone, or a high and falling tone. All sorts of slapstick confusion can result when Westerners voice tones ambiguously or incorrectly, as all but the most brilliant polyglots almost invariably do.

Thankfully, our exploration of China’s history and culture need not involve the life-spanning task of mastering the language. It will suffice for our purposes to deal with it at a further level of remove. Yet even coping with its complications in translated form can be thoroughly off-putting.

How do you write the native proper nouns of a language so utterly alien using an alphabet designed for European languages? Westerners have been struggling with this issue for a long, long time. In some cases, such as those of Mount Everest and the Yellow River, we have simply ignored the Chinese names for things in favor of new designations which we have made up ourselves. In other cases, people have done the best they can to create phonetic transcriptions of spoken Chinese. For example, George Macartney on his visit to China meticulously spelled out “Van-ta-gin” and “Keen-sa-ta-gin” as the names of two of the mandarins who assisted his party. One can’t help but picture him sitting there in his stoic but slightly clueless British way, journal in hand, asking his translator to repeat the Chinese pronunciation again and again while he tries to tease out the strange sounds of the syllables.

The British linguist Thomas Francis Wade became the first to begin to work out a more rigorous system of “romanizing” Chinese during the middle years of the nineteenth century. His approach was codified and popularized by his colleague Herbert Giles in his landmark Chinese-English Dictionary of 1892. Until the 1970s, this Wade-Giles system was the well-nigh universally accepted way of writing Chinese names using the Latin alphabet.

Meanwhile prominent Chinese intellectuals of the early twentieth century who were desperate to drag their country into the modern world argued for a wholesale abolition of the traditional Chinese script and its replacement with Wade-Giles or some other phonetic system — a system whose smaller number of simpler glyphs would make it far more amenable to such staples of modern life as printing presses and typewriters (not to mention the computer keyboards and monitors that were waiting in the wings). When the Chinese Communist Party seized power in 1949 with the backing of some of those same intellectuals, many believed just such a project to be all but a foregone conclusion; Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had done it for Turkish, so why couldn’t Chairman Mao do it for Chinese? And sure enough, the new government began publishing drafts of a romanization standard known as Pinyin soon after. Yet the wholesale changeover that so many had confidently expected was never brought off, not even amidst the frantic top-to-bottom social deconstruction of China that was the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976. The most the Party deigned to impose were simplified versions of the old ideographic glyphs which were easier for the technologies of mass communication to reproduce.

But Pinyin didn’t go away; it remained the government’s official standard for romanization in those situations where it was absolutely necessary. It has gradually become the accepted way of writing Chinese using the Latin alphabet outside of Communist China as well. Pinyin has won out because it is on the whole the superior system: it replicates the sounds of spoken Mandarin generally better than Wade-Giles. But it should be emphasized that both systems are in the end crude approximations of the real sound of the language, which refuses as obstinately as ever to line up neatly with our Latin alphabet; for example, the sound that Wade-Giles represents as “p” and Pinyin as “b” lives in reality at a point suspended right in between the two Latin consonants. Thus the differences between words written in the two systems can be considerable without either of them managing to get it quite right: the Wade-Giles Mao Tse-tung is Mao Zedong in Pinyin; Peking is Beijing; Szechuan is Sichuan; Yangtse Kiang is Yangzi Jiang.

All of this is a recipe for serious confusion for the Western student of China. Not only is she confronted with a profusion of strange, often similar-looking names, but the name for the same place or person may be completely different from book to book, depending on each tome’s vintage. In addition, there are some names — either blatantly Western appellations like Mount Everest and the Yellow River or imperfectly transcribed Chinese ones — which predate even Wade-Giles, and have become so embedded in common usage that they cannot be extricated. For instance, how often is Confucius referred to in the West by his proper Pinyin name of Kong Fuzi?

In this book, I will strive to be internally consistent if nothing else. I will generally hew to the Pinyin system, but not to the point of denying you the welcome familiarity of names you may actually recognize; I will use the standard Westernized names for figures like Confucius even at the risk of being accused of cultural imperialism. When quoted sources use the Wade-Giles or some other variant version of a name, I will usually take the liberty of quietly replacing it with its Pinyin equivalent. In only one case will I ask you to hold in your mind two variations on the same name. That exception is the capital city of Beijing, which was known in the West until the 1970s as Peking.

Let me close with a word about Chinese names for individual people. These do generally consist of a given name and a surname, just like in the West, but to that degree of familiarity must be attached a number of unfamiliar caveats. With the exception only of some Westernized Chinese who have adapted their names to our system, Chinese surnames come first, given names second; thus Mao is the surname, Zedong the given name. It is typical for surnames to have just one syllable, for given names to have two. The pool of possible surnames is an order of magnitude more restricted in China than it is in most Western cultures: just three surnames suffice for more than 20 percent of the Han Chinese population, while the top 100 are enough to cover 85 percent of all living Chinese. The inevitable duplication of names that results from this combination of few naming possibilities with gigantic numbers of people is, needless to say, another possible source of confusion in many contexts, but it shouldn’t be a problem in the fairly high-level overview of Chinese history that is our current project.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Aula

“in addition to being the most populous of them all”

For now; most likely it will be a matter of only a few decades until India passes China in terms of population.

“the China of today is physically as large as it has ever been”

But it doesn’t hold all the territory it has ever held; Vietnam was under Chinese rule for very nearly one thousand years.

“and carry no clue on the page as to their their pronunciation in the spoken language”

Duplicate “their” in that sentence. Also it isn’t quite true; well over half of all Chinese characters are phono-semantic compounds, composed of one simpler character that has a related meaning and another simpler character that has a similar pronunciation (or at least has had at some point in the history of the language).

Jimmy Maher

Added a qualifier or two to my description of written Chinese. Thanks!

Martin

So if the syllable “ma” can mean “mother” if it pronounced the right way, how do the Chinese put emotion into their speech? Seems like a minefield or a cause of very unemotional speaking.

Also, you said the south still has an affinity for “earth magic”. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Jimmy Maher

I’m no expert on Chinese speech, but I assume there are ways to convey emotion that don’t interfere with the tones that are used to express meaning. What seems a “minefield” to the uninitiated seems perfectly natural to a native speaker. I realize it can be hard to remove yourself from a context that’s the only one you’ve ever known — but nevertheless, the way language works in the West is not the only way language *can* work.

That said, the use of tones to convey meaning isn’t *completely* alien to even English. The classic example is raising the pitch at the end of a sentence to convey that it’s meant as a question.

There’s a traditional Chinese belief in veins of spiritual power that run through the earth, not all that far removed from similar Western New Age beliefs. (See: Sedona, Arizona.) Come to think of it, the former is probably the original source of the latter. 😉 As we’ll learn in the next chapter, the oldest Chinese creation narratives describe the world as being made out of the literal body of Pangu, the creator god. Thus there are some interesting parallels between traditional Chinese medicine on a micro scale and geomancy on a macro scale.

Ross

I do wonder whether “So overcome by emotion that they are using malapropisms” would be a popular and relatable trope in tonal languages.

Josh Martin

They do it pretty much the same way English-speakers do. If you’re angry then you might pronounce a word or sentence with a sharp staccato sound resembling the fourth (falling) tone in Mandarin; if you’re inquisitive you might turn a statement into a question by putting a rising inflection at the end, like the Mandarin second tone. All languages have a tremendous amount of built-in redundancy that makes it possible to drop or alter a certain amount of phonetic information and still retain intelligibility. If this weren’t the case, speakers of different American English dialects and accents wouldn’t even be able to understand each other, much less speakers of non-American English.

Speaking more specifically of Chinese, tone seems to be the most variable and arguably disposable aspect of Chinese speech. Tonal differences are perhaps the most common distinction between different dialects of the same language—for example, Qingdao Mandarin semi-systematically swaps the first and third tones and merges the second and fourth, but by and large it’s still comprehensible to speakers of other Mandarin dialects so long as locally-specific vocabulary isn’t used. Orthographies based on the Latin (Sin Wenz), Arabic (Xiao’erjing), and Cyrillic (Dungan) scripts have been used by speakers of Mandarin or closely-related languages as a full substitute for characters and none of them mark tones outside a handful of special cases, like Sin Wenz Shansi vs. Shaansi (which likely influenced the current romanizations Shanxi and Shaanxi). Chinese when sung will also frequently ignore “correct” tones for the sake of melody, without necessarily impairing intelligibility.

Let’s take the example of four mas. One of these, mà “to scold,” is a completely different part of speech, so it can’t be confused with the others any more than the English “sea” could be confused with “see.” The other three are all nouns, but the situations where it might be unclear if someone is referring to “mother,” “hemp,” or “horse” have to be vanishingly rare. Furthermore, most modern Chinese vocabulary is polysyllabic, including the word for “hemp”: in Mandarin one wouldn’t refer to hemp as just má but as dàmá, a word that exists má by itself has been used at various times and places over the centuries for different fibrous plants like jute, flax, and even sesame, prompting the development of polysyllabic words to distinguish the different types of má (see also yàmá “flax,” huángmá “jute,” zhīma “sesame”). The heavy use of polysyllabic words reduces the prevalence of homophony and increases the odds of being understood if certain phonetic features are altered or dropped altogether, whether it’s say, the tendency of Southern Mandarin dialects to merge the retroflex initials zh-/ch-/sh-) with the denti-alveolars z-/c-/s-, or the innumerable native Mandarin speakers who muddle the finals -n and -ng. None of this is to say that tone is inessential, but it’s just one feature among many.

Michael

“And yet its grammar is as childishly simply” should probably be “childishly simple”.

A teacher with whom I used to study Mandarin once told me that spoken Cantonese had a lot more grammar, and that Mandarin had been “simplified” around the Cultural Revolution, but I haven’t ever tried to verify this; it’s just one of those little pieces of unreliable trivia that probably end up being the source of falsehoods.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

I can’t speak to Cantonese, but the extreme simplicity of Mandarin grammar was being noticed and remarked on by Westerners during the nineteenth century if not before. I believe the reforms introduced shortly after the Communist takeover were focused more on the written than the spoken language.

Chops

“Much of our confusion tends to stem from our desire to see China as all one thing.”

Which links interestingly to the current doctrine within China of exactly that. One people, one history, one language, all that sort of thing; the current ruling party in China insists on this and it causes the kind of problems you would imagine. It remains to be seen if they can force this, or if the whole project will fall apart.

Gareth

Love this article really looking forward to reading the series. One thing that really jarred with me: I’d never heard of Alasdair Clayre but is it really reasonable to imply that he killed himself because he was worried his book wasn’t very good?

Jimmy Maher

Yes, the story is fairly well-documented. Obviously no one kills himself for one reason only, but his project — not just a book actually but an accompanying BBC documentary series — really was the stated proximate cause. But I do admit I was slightly concerned — not so much about the accuracy of the assertion but about whether I might seem to be treating a tragic event too glibly. In the end, I included it, but I’m still a bit torn. Maybe it comes out at some point. 😉

Gareth

It did seem rather glib in my opinion. And a recent enough event that I’m sure some affected are still very much around.

Jimmy Maher

Fair enough. It’s gone.

Will Moczarski

may have led it to development the institutions of government

-> to develop

hold in your mind two variation on the same name

-> variations

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!