History is not neatly compartmentalized like the chapters of a book such as this one. It is rather a messy business, full of epochs and events that bleed into one another. Well before the Second World War was finished, for example, the democratic West and the communist Soviet Union had already begun jockeying for position in the postwar world. As part and parcel of this, a year or more before the end of the war, the government of the United States turned with some urgency to the question of what the postwar era in China would look like. Chiang Kai-shek’s government was tottering, hollowed out from within by mismanagement and rampant corruption, while the Communists were going from strength to strength. The United States therefore did its best to broker a compromise that would prevent a Chinese civil war from breaking out as soon as the Japanese threat was no more. For if, as seemed likely, the Communists came out on top in such a war, the most populous nation in the world would fall into the Soviet sphere of influence.

President Roosevelt delegated the task of negotiating a rapprochement between Chiang’s government and the Communists to a former American secretary of war named Patrick J. Hurley, a plainspoken unreformed Oklahoma country boy who knew nothing about China before arriving there in 1944 and would learn little more about it over the course of his stay; from first to last, he pronounced Mao Zedong’s name “Moose Dung” and called Chiang Kai-shek “Mr. Shek.” On November 7, 1944, he became the first high-ranking American diplomat to travel personally to Yan’an, for talks that he hoped would lead to some sort of postwar power-sharing arrangement between Mao and Chiang. He totally failed to recognize what was obvious to everyone with actual experience in China: that neither side was negotiating in anything like good faith, that Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek were constitutionally incapable of sharing power with others, much less their most enduring enemies. The dispatches Hurley sent back to Washington are breathtaking in their naiveté. “Two fundamental facts are emerging,” he wrote. “The Communists are not in fact communists; they are striving for democratic principles. And the one-party, one-man personal government of the Kuomintang is not in fact fascist; it is striving for democratic principles.” In reality, of course, neither side cared a straw for “democratic principles,” at least not in the sense that Hurley understood them.

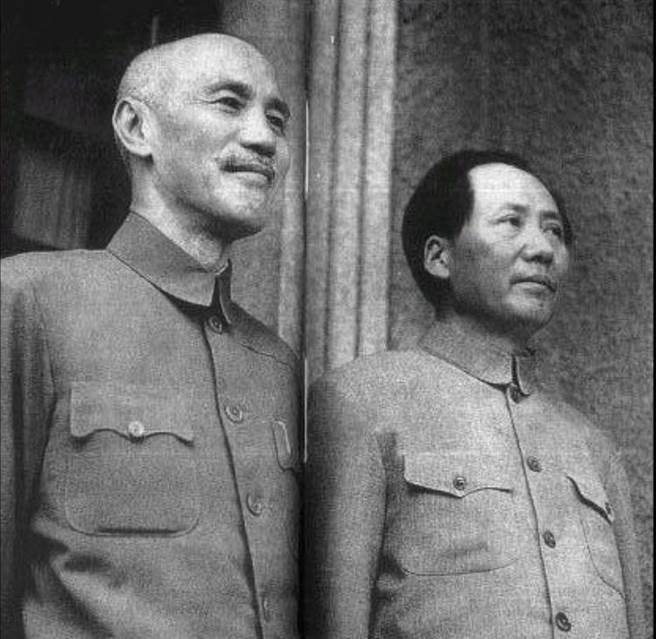

But Hurley kept right on believing what he wanted to believe, and was soon elevated to the post of American ambassador to China on the wings of his optimism. He begged Mao Zedong to come to Chongqing personally to meet with his opposite number on August 16, 1945, just two days after Japan had sued for peace. Mao was extremely worried about his own safety in his enemy’s capital, as well he should have been, but he finally agreed after Hurley promised to provide him with an American military escort from the moment his plane took off from Yan’an until the moment it touched down there safely once again. There followed seven weeks of absurd political pantomime, with the two leaders scarcely concealing their deadly loathing for one another under a thin veil of formal correctness, whilst agreeing to exactly no concrete resolutions. It was enough to convince even Hurley that the two men’s differences truly were intractable; he resigned his ambassadorship shortly thereafter, thus ending his China adventure.

Just days after Hurley left the country, no less important a figure than General George C. Marshall, the “organizer of victory” in Europe in the words of Winston Churchill, arrived to have another go at making China safe for democracy. He talked tough to Chiang: “Inasmuch as you cannot hope to obtain military victory over your opponents without massive American aid, which is utterly out of the question, and since, on the other hand, your opponents the Communists are in a position to obtain covert Soviet aid sufficient to overthrow you by force of arms, it follows that [your] only hope lies in a political settlement.” But Chiang’s circumlocutions proved too much even for Marshall’s considerable talents. Chiang agreed in principle to a power-sharing arrangement that would make of China first a multi-party state and in time — hopefully! — a real democracy. Then, three days after Marshall’s departure, he reneged on his acquiescence in its entirety. Marshall returned to China repeatedly over the course of 1946 to try to repair the situation, but he never succeeded. Instead he became the American secretary of state, from which position he set about crafting his Marshall Plan to repair and heal war-ravaged Europe — a relatively straightforward task in comparison to the challenges of Chinese diplomacy.

The prospect of Soviet intervention to which Marshall had alluded was more than just a theoretical possibility. In the dying days of the Second World War, Joseph Stalin had declared war on Japan — something which the United States and Britain had been begging him to do for years by that point — and launched a swift and successful invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Korea. Now, with the war over, the Soviet Union positively loomed over the heart of Inner China. It promptly handed Manchuria over to the Communists. (The Soviets also handed over the hapless Puyi, who had been the last Qing emperor and then Japan’s puppet emperor in Manchuria; the Chinese Communists “reeducated” him in work camps, then released him many years later, using him as a propaganda tool after he publicly expressed his “deep regrets” for his actions.) In the summer of 1946, Stalin commenced delivering significant military support to the Communists, giving them more than 1200 heavy artillery cannons, almost 400 tanks, 300,000 rifles, 5000 machine guns, and 2300 trucks and other vehicles. For the first time ever, the Communists could fight Chiang’s armies on a level playing field.

It was an ominous development for Chiang, given that no corresponding level of support for his own side was forthcoming from the United States. President Roosevelt had died in April of 1945, whereupon his post had passed to his vice president, Harry Truman. Truman possessed none of his old boss’s sentimental attachment to China. On the contrary, he had spent the Second World War raging against the corrupt China Lobby and Chiang’s do-nothingism, and, following the failed diplomacy of Patrick Hurley and George Marshall, was inclined to abandon the generalissimo to his fate, even if it meant a dramatic expansion of the Soviet sphere of influence.

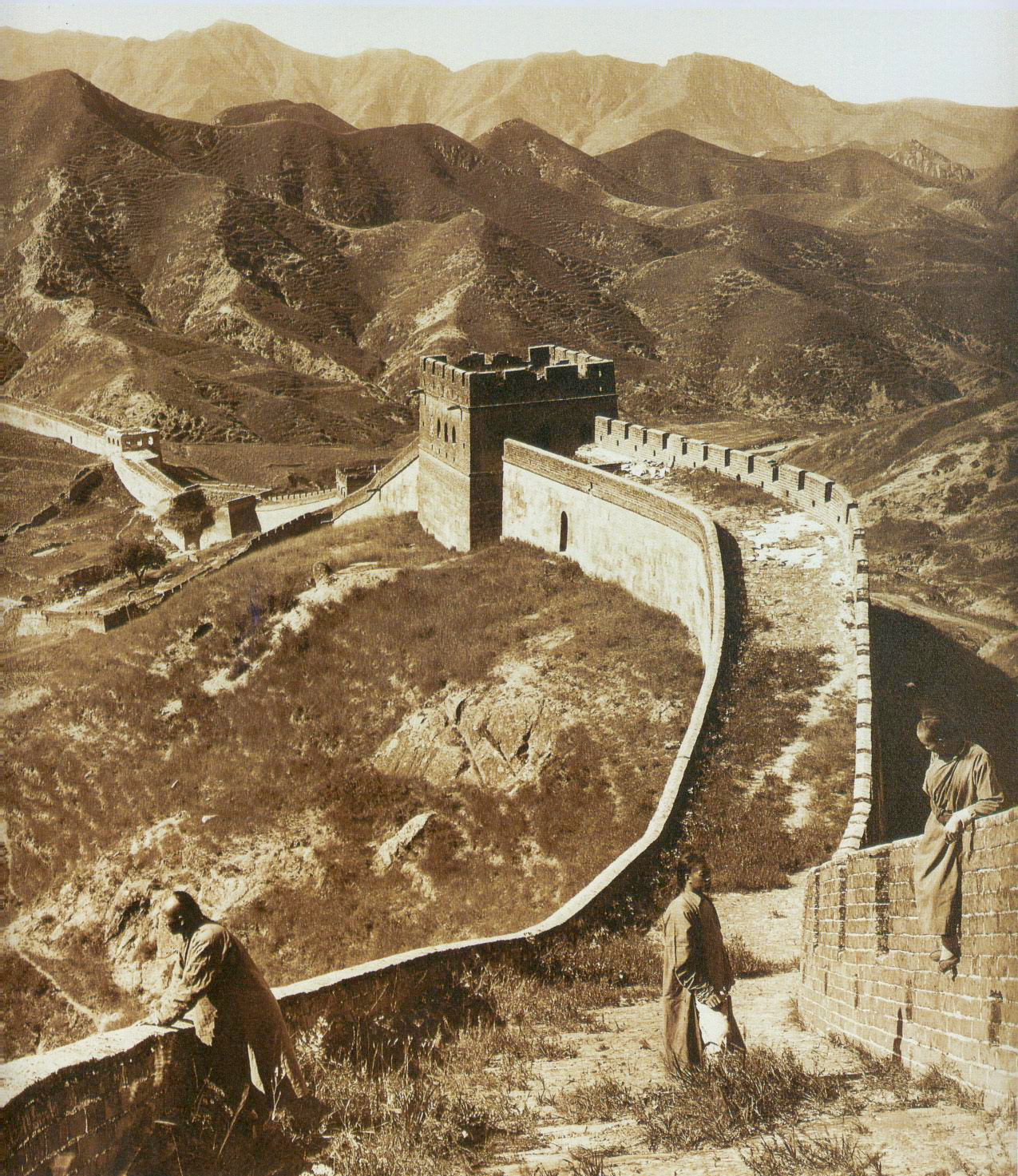

But still Chiang refused to countenance any settlement that left him as anything other than the undisputed leader of all of China. In the face of such intractability, the inevitable soon came to pass: the rival camps set about settling the issue with guns. Showing far more enthusiasm for fighting his countrymen than he had ever displayed for fighting the Japanese, Chiang set up a base of operations in Beiping, whence he sent armies over the Great Wall into Communist-controlled Manchuria.

The campaign proved a disaster. Mao Zedong, that genius of asymmetric warfare, used propaganda leaflets as effectively as he did guns and tanks, convincing entire battalions of poorly fed, press-ganged soldiers to defect to his side without firing a shot. Other soldiers simply disappeared, leaving their American-made weaponry lying on the battlefield for the Communists to pick up and use. (An American military advisor to Chiang claimed that by the end of the civil war “the Communists had more of our equipment” than did Chiang’s remaining armies.) In all, Chiang lost 400,000 soldiers in Manchuria to death, injury, or defection. By the middle of 1948, the shoe was on the other foot: it was the Communists on a full-scale offensive, encircling Beiping and pushing as effortlessly down the eastern seaboard of Inner China as the Japanese had done a decade before. Unlike the Japanese, however, they were welcomed as liberators by the ordinary Chinese who lived there. On November 30, 1948, the staff of the United States embassy in Nanjing, the city to which Chiang Kai-shek had returned his capital after the war with Japan was over, was ordered to begin evacuating.The end was nigh; Chiang’s incarnation of China was in self-evident collapse.

Soong Mei-ling departed for the United States in order to make a last desperate plea for American intervention. Heeding at last the criticisms that had swirled around her on her previous visit, she left her fur coats at home this time and traveled with a much smaller entourage. But her cause was lost on President Truman, whose assessment of her, her husband, and their cronies had only hardened in the postwar years; he had taken to calling Chiang Kai-shek “Cash My Check” in private.

They wanted me to send in about 5 million Americans to rescue [Chiang], but I wouldn’t do it. He was as corrupt as they come. I wasn’t going to waste one single American life to save him. They hooted and hollered and carried on and said I was soft on communism, but I never changed my mind about Chiang and his gang. Every damn one of them ought to be in jail, and I’d like to live to see the day they are.

They stole [the money] that we sent to Chiang. They stole it, and it’s invested in real estate down in São Paulo and in New York. And that’s the money that was used and is still being used for the so-called China Lobby. I don’t like that. I don’t like that at all. And I don’t want anything to do with people like that.

We picked a bad horse…

The public pronouncements that came out of the White House were almost as unsparing. Chiang had, according to them, “made a tragic mockery of both American and Chinese hopes for a free and democratic China.” It was a stunning reversal of the attitudes of 1943, when Soong Mei-ling had been treated as international democracy’s Joan of Arc. The American press felt free now to openly mock her airs: she was “an unpredictable mixture of a Chinese lady tyrant and an American girl sophomore.” And yet she would remain in the United States for more than a year in the face of such scorn. In fact, she would never set foot on mainland China again.

Beiping fell on January 21, 1949, and was renamed Beijing again by the Communists, who made it their capital. Chiang had by now returned to his old bolthole of Chongqing. Aware that his defeat was a foregone conclusion, but ever the survivor, he busied himself with moving his government’s remaining gold reserves and military equipment and even nearly a quarter of a million precious museum objects to the place he had chosen as his final refuge: the island of Taiwan, which had been under Japanese control from 1895, but had been returned to China at the close of the Second World War.

On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong, chairman of the Communist Party of China, stood before a crowd of hundreds of thousands in Beijing’s Tienanmen Square to proclaim the formation of a People’s Republic of China. “This government is willing to establish diplomatic relations with any foreign government that is willing to observe the principles of equality, mutual benefit, and mutual respect of territorial integrity and sovereignty,” he said. Within hours, the Soviet Union became the first country in the world to officially recognize China’s new government.

Also standing on the stage on that monumental day, representing the spirit of her dead husband Sun Yat-sen, was Soong Ching-ling, who had done her best during the war years and after to foster a compromise between the government her family ran and the Communists, but had finally been forced to choose one or the other. Being the Soong sister who loved China most of all, she had felt obligated to pick the Communists in defiance of all of the Confucian values of fileal piety, thus precipitating the final, irredeemable rupture between herself and her siblings that they had managed to avoid for so long. In the years to come, she would be awarded the Stalin Peace Prize (an oxymoronic name if ever there was one) and would be named Vice Chairman of the People’s Republic, a rank that placed her in theory below only Chairman Mao himself. The home in Shanghai where she had lived with Sun Yat-sen became a national shrine, while she moved back into Charlie Soong’s old house, the same one in which she had grown up with her siblings during very different times.

Said siblings were scattered hither and yon by the winds of civil war, but all made safe landings using their parachutes of wealth. H.H. Kung and his wife Ai-ling, the Soong sister who loved money above all else, took up residence in New York, where they would be the subject of several law-enforcement investigations into the sources of their enormous fortune, but would never be formally charged with any crime. Mei-ling, the sister who loved power, was staying with Ai-ling in New York when Ching-ling was standing alongside Chairman Mao in Beijing, but was making plans to return to Chiang Kai-shek if and when he could set up a stable base again on Taiwan. Meanwhile their brother T.V. Soong had gone to Hong Kong, whence he would deal energetically in commodities and technology in the years to come, becoming a living embodiment of the British colony’s long tradition of unfettered laissez-faire capitalism, and becoming in the process, according to local legend at least, “the richest man in the world.”

On December 10, 1949, Chiang flew from Chongqing to Taipei, the largest city on Taiwan, now to be the latest capital of this leader who had gone through more of them than any other ruler in Chinese history. His official position was that he was merely making a tactical retreat to the island, to regroup and launch a triumphant counteroffensive that would wipe out the Communists once and for all. The reality was very different; like his wife, Chiang had now trod on the soil of mainland China for the last time.

Taiwan is an island slightly smaller than the nation of Denmark that lies at its closest point barely 80 miles (130 kilometers) off the coast of Southern Inner China. A rugged place of jungles and crags, Taiwan was not considered an integral part of China for most of that land’s long history, contrary though this is to present-day Communist Chinese rhetoric. The native population, who had been living there for thousands of years already even in the time of the Han dynasty, were fiercely independent and didn’t hesitate to defend themselves against venturesome mainlanders, even as the island’s jungles teemed with equally deadly diseases. An enclave of breathtaking beauty, Taiwan was nevertheless seen for many, many centuries as an ill-starred place that was best avoided.

It was actually the Japanese rather than the Chinese who first established a toehold on Taiwan in the middle of the second millennium of our epoch; the good fishing hereabouts made it an ideal way station for ships and boats sailing between the Japanese home islands and other parts of East Asia. Then the Europeans came along. (The once-standard alternate name for Taiwan in the West, Formosa, stems from the Portuguese Ihla Formosa, or “Beautiful Island.”) The Spanish settled a piece of Taiwan in 1626, only to be driven off by the Dutch in 1642. These Europeans cleared swaths of jungle, laying bare for agriculture the fertile soil beneath, and built missions, schools, and institutions of government. With the mainland then passing through the chaotic transition between the Ming and the Qing eras, many hardy Chinese chose to emigrate to the comparatively prosperous and peaceful Taiwan.

In 1662, a group of Ming loyalists fleeing the Qing takeover of the mainland drove the Dutch away. They ruled Taiwan for about twenty years thereafter, until it too fell to the waxing Qing dynasty. But it had still not entirely shed its former wild reputation; it was owned by China but not quite considered of China, being a haven of pirates and smugglers, with headhunters still rumored to be lurking in its deepest heart of darkness. Not until 1887 did the Qing raise Taiwan to the status of province in its own right, thus finally making it by implication an indissoluble part of China. Just eight years later, Japan gave the lie to that proposition by defeating the Qing in war and taking Taiwan for itself.

Taiwan’s half-century as a Japanese possession brings to mind the old saw about Mussolini and trains that run on time. The population was beholden to a military regime that couldn’t have cared less about such niceties as home rule or civil rights. By way of compensation, however, Japan, by far the most modern nation in East Asia during the period, brought other fruits of progress to Taiwan, in the form of factories, infrastructure, a solid legal framework, and public education. By the beginning of the Second World War, 80 percent of Taiwan’s population was literate, a direct inverse to the proportion of mainland Chinese. Taiwan’s economic and logistical contribution to the Japanese war effort was significant enough that the Allies seriously discussed invading it before the Japanese home islands, but such discussions were rendered moot in the end by the atomic bomb.

After the war was over, Taiwan was handed over to Chiang Kai-shek’s government, which soon made many locals miss the days of Japanese occupation. For the provincial governor whom Chiang appointed was as brutal as the Japanese had been but far less effective. He saw his new subjects as Japanese collaborators, and believed that this justified any punishment he chose to mete out to them. “We think of the Japanese as dogs and the Chinese as pigs,” said one islander. “A dog eats, but he protects. A pig just eats.”

Over the course of 1949, Taiwan’s population swelled from 9 to 11 million, as a tidal wave of soldiers, bureaucrats, well-to-do bourgeoisie, refugees, and conscientious objectors to communism washed up on its shores, followed at last by their dear leader himself. The Taiwanese didn’t want them; any spark of loyalty they might have felt toward Chiang’s regime after the war had been long since extinguished by their exposure to the day-to-day reality of it. But they were stuck with them.

The question was, for how long? Mao Zedong made it clear that he would not consider his revolution complete until Chiang Kai-shek was defeated for good, and Taiwan too flew the newly minted blood-red flag of the People’s Republic of China. President Truman, for his part, felt no more inclination to protect Chiang in his last redoubt than he had during the rest of the civil war that had preceded this exigency. On January 5, 1950, he announced that the United States did not “have any intention of utilizing its armed forces to interfere in the present situation. The United States will not pursue a course which will lead to involvement in the civil conflict in China. Similarly, the United States will not provide either military aid or advice to Chinese forces on Formosa.” Shortly thereafter, the British government granted diplomatic recognition to Mao’s regime as the true government of China. There were rumblings in Washington that Truman’s State Department was soon to do the same.

It seemed that the Communists had carte blanche to take Taiwan. They were hindered only by the failings of their own military — namely, that they had almost no navy or air force whatsoever for launching an amphibious invasion. Chiang, on the other hand, had about 70 ships and boats and some 600 airplanes, the latter still regularly harassing the coastal cities of Inner China under the command of the ever-loyal Claire Chennault, who had resigned his commission in the American military after the Second World War in favor of staying at the beck and call of his Chinese patron. Never mind, thought Chairman Mao; Chiang Kai-shek obviously wasn’t going anywhere, leaving him with time to prepare an invasion at his leisure.

With her mission in the United States having proved a bust, Soong Mei-ling made one of her trademark melodramatic — not to say passive-aggressive — exits. She was, she said over the American airwaves on January 8, 1950, returning “to my people on the island of Formosa, the fortress of our hopes, the citadel of our battle against an alien power which is ravaging our country. Chiang Kai-shek, of all the world’s statesmen, was first to perceive the treachery of the Communists. A few years ago he was exalted for the courage and tenacity of the fight he waged. Now he is pilloried. Times have changed, but the man has not changed. My husband remains resolute.”

Contrary to Mei-ling’s defiant public promise to fight to the last, she and her husband were quietly laying the groundwork for asylum in the Philippines, if and when it came to that. But then the whole situation was upended by another event, one that The New York Times called “the biggest piece of luck Chiang Kai-shek [has] had in his 30-year losing streak.”

In addition to Manchuria, the Soviet Union had in the course of its last-minute entry into the war against Japan seized the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. An uneasy standoff had followed the Second World War in Korea, with one half of the country being rebuilt by the Soviets on communist principles under a native Korean leader named Kim Il Sung, the other half being rebuilt by the Americans, ostensibly on the principles of liberal democracy, under another Korean named Syngman Rhee. On June 25, 1950, the standoff ended, when 90,000 North Korean troops equipped with the latest Soviet-made weaponry swept suddenly southward, in an attack that absolutely no one in the West had seen coming.

The last flickering hopes for a more harmonious postwar world order, presided over by a benevolent United Nations (the replacement for the ineffectual old League of Nations), died on that day, as the world embarked irrecoverably upon the Cold War, that 40-year shadow conflict between communism and democracy, with the terrible specter of nuclear apocalypse hovering constantly over the proceedings. A year earlier, James Forrestal, Truman’s secretary of defense, had warned that “we can’t wreck our economy trying to fight the ‘cold war.'” After June 25, 1950, no one in the United States would ever put that neologism in scare quotes again; nor would mere questions of finance be allowed to stand in the way of the need to keep communism at bay.

The new American strategy was that of containment — i.e., checking communism anywhere and everywhere it tried to advance, even if doing so entailed getting into bed with other shady characters who just happened to be of an anti-communist bent. The Truman administration’s attitude toward Chiang Kai-shek’s beleaguered regime changed almost literally overnight. On June 27, in the same speech in which he announced that the United States would be mounting a major military effort to protect South Korea, President Truman said that his country would also guarantee the safety of Taiwan against communist aggression. (In the spirit of fairness, he did demand as well that Chiang cease his air raids on the mainland, which the latter grudgingly proceeded to do.) On July 31, General Douglas MacArthur, a larger-than-life hero of the Second World War who was now in charge of the rebuilding of Japan and much else in East Asia, made a flying visit to Taiwan to underline the new American position that Chiang’s tiny island outpost housed China’s one and only legitimate government in exile, in the same sense that the governments of those European nations conquered by Nazi Germany had also once been forced to set up temporary shop elsewhere. This insult to the genuinely popular revolution that had swept Mao Zedong into power still burns red and raw in the souls of China’s leaders to this day.

The Western press was filled with speculation as to why and how the North Koreans had chosen to mount this unprovoked invasion, and particularly whether Mao Zedong and/or Joseph Stalin had pressured them into it. In truth, however, the final decision had been Kim Il Sung’s alone. He had looked with envy upon Mao as the latter brought one of the largest countries in the world under his sole control. Meanwhile he was convinced by the failure of the Americans to intervene to save Chiang Kai-shek that they would not want to entangle themselves in an extended war over Korea either. Mao believed the same and was supportive of Kim’s plans, but Stalin was willing neither to pledge his wholehearted support nor to categorically tell Kim that he was not allowed to invade. “If you should get kicked in the teeth, I shall not lift a finger,” said Stalin. “You have to ask Mao for help.” Kim scoffed at this, noting correctly that his own troops were actually better-equipped than most of Mao’s. The war would be over so quickly, he said, that a unified communist Korea would be the reality on the ground before the Americans had time to catch their breath. Confronted with the prospect of a long, bloody struggle to retake that which had been lost in a part of the world about which most American citizens knew little and cared less, they would rattle their sabers a bit and let sleeping dogs lie.

The initial assault lived up to his billing. The North Korean army outnumbered that of the South by two to one, and had the advantage of advance preparation. Syngman Rhee had been something of protégé to Chiang Kai-shek in recent years, and his government bore many similarities to that of Chiang: it and its leader were, as the military historian Clay Blair writes, “devious, emotionally unstable, brutal, corrupt, and wildly unpredictable.” In short, South Korea’s government was no better equipped to withstand a populist assault in the name of communism than Chiang’s regime had been before it. Meanwhile the American troops in the country were spread far too thinly to put up a credible defense. The South Korean capital of Seoul, which lay just over the border, was secured by the North within three days. By September, the war seemed all but over, with the remaining South Korean and American forces pushed back into a small pocket in the extreme southeast of the peninsula.

Then, on September 15, General MacArthur led a daring amphibious landing at Incheon Harbor, on the west coast of the peninsula, almost as far north as the original border between North and South Korea. The audacious gamble was spectacularly successful, throwing the North Koreans into a panic. Seoul was reclaimed on September 28, as the North Korean armies scurried madly back toward the border in order to avoid being cut off and surrounded in enemy territory. MacArthur gave the civilian politicians in Washington no chance to debate the wisdom of chasing them into their home territory; he simply did so on his own initiative. The North Korean capital of Pyongang fell on October 19 to cap off one of the most head-snapping reversals in the history of warfare. MacArthur told his soldiers that they would all be back home in time for Christmas, leaving behind them a unified democratic Korea. But the pendulum was about to swing the other way again.

For Chairman Mao had decided, against the advice of virtually everyone in his government, to save Kim Il Sung by sending Chinese soldiers into North Korea. Just five years earlier, he had been a party to peace negotiations mediated by earnest Americans. Now he was prepared to meet them face to face on the field of battle, something even Stalin was always careful to avoid. He was willing to do so because the North Koreans were his brethren communists, but also for a more practical reason: Korea bordered on Chinese Manchuria, and he had no wish to rub shoulders with an American client state. And it must be admitted that his wariness about such a scenario was not completely misplaced. Some in the United States, including the still-influential Henry Luce, were openly advertising the Korean War as just the first front in a broader Asian conflict that would ideally lead to the “liberation” of China. (Chiang Kai-shek, whose appetite for seeing others do his fighting for him was insatiable, was avidly hoping for the same outcome from his Taiwanese exile.)

Mao chose as the instrument of North Korea’s rescue his favorite general, Peng Dehuai, a grizzled old soldier who, it was said, was so used to campaigning that, when he found himself bivouacked in a room with an actual bed, preferred to lie down on the floor next to it. Peng had already begun stealthily moving hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers into North Korea not long after Seoul fell. They lay in silent wait for the heedlessly advancing Americans. In the bitter cold of an encroaching winter in the mountains, Peng watched as they wandered casually into indefensible valleys and canyons, having been told by their own leaders that the war was effectively won already. Then, on the night of November 25, he struck. For the Americans, it was like walking into a buzz saw. The transcript of one radioman’s increasingly frantic dispatches reads like the script of a horror movie: “They’re hitting us! My God, they’re everywhere… We’re holding, but they’re all over the place… Every time we stop them, more come… We can no longer hold. There are so many of them… This may be the last message you get from us…”

Even as he had insisted that Mao would never dare to enter the war, MacArthur had consistently underestimated the new China’s military potential if he should do so, basing his evaluations on the pathetic performances of Chiang’s armies during the Second World War in addition to the usual racist and chauvinist assumptions. He was swiftly disabused of all such notions now. What Peng’s soldiers might have lacked in the latest kit they more than made up for in bravery, experience, and esprit de corps. They were, after all, mostly hardened veterans, some of them with service histories dating back to the Chinese Soviet Republic and the Long March; suffice to say that they had staged more than a few ambushes in their lives. The Americans were soon in headlong retreat everywhere on the front line, their plight made still worse by bad weather that kept their aircraft — under other conditions their trump card — stuck on the ground.

It is very difficult to overstate the importance of this victory to the new Chinese sense of themselves and to the future political prospects of Chairman Mao, their new leader. For the better part of a century and a half, China had been bullied by the rest of the world, suffering defeat after abject defeat. Now all that shame had been erased; General Peng had met the best soldiers that the richest country in the world could throw at him and sent them running back in the direction they had come from in a blind panic. “Our nation will never again be an insulted nation,” Mao had promised just the year before. “We have stood up. No imperialist will be allowed to invade our territory again.” Now he had made good on that promise. China’s time of humiliation was well and truly over.

Yet there were limits to even Mao’s ambitions for the conflict in Korea. He did not want the Korean War to escalate into the sort of full-on war between Communist China and the United States that was being promoted by the likes of Henry Luce and Chiang Kai-shek. He had only to look to the recent fate of Japan to know that his impoverished nation would stand little chance against such an enemy if said enemy was absolutely committed to victory at any cost. He therefore referred to the soldiers he sent into Korea as “volunteers,” pretending that China as a whole was not really fighting even a limited war with the United States. (That he could do so while at the same time basking in the glory of the Chinese army’s victories over the Americans is testament to the nearly infinite capacity of human beings to hold contradictory but equally self-serving thoughts in their heads at the same time.)

The Korean War thus became one that neither side still wanted to be fighting, but neither knew how to end. The Americans had already held the line against communism by stopping Kim Il Sung from taking over the entire Korean peninsula, while the Chinese had proved their mettle against the best the West could offer and kept the Americans well away from their own territory through their counteroffensive. Now both sides were equally wary of the war escalating any further. By the new year, the Americans had begun to get their act together and to stabilize the war along a front that ran through the middle of the peninsula, roughly where the border had always been. And the Chinese, for their part, were feeling the bite of stretched supply lines through mountainous terrain and of American air superiority, at the hands of which they suffered horribly, to the tune of eight Chinese soldiers killed for every one American. The war became a stalemate and a quagmire. Perhaps one side or the other could have changed that if it had really wanted to — but, again, neither actually did for fear of what the consequences might be. That became abundantly clear on the American side on April 11, 1951, when President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his command for persistently and publicly pushing for the broader war which his country’s civilian leadership had decided was thoroughly ill-advised, given the risk of it turning into a third world war if the Soviet Union should see fit to more wholeheartedly support its communist friends — this being the same Soviet Union that had tested its first atomic bomb two years earlier.

So, the Korean War became, in the words of journalist David Halberstam, “a war of cruel, costly battles, of few breakthroughs, and of strategies designed to inflict maximum punishment on the other side without essentially changing the battle lines.” It went on and on and on on those terms, the first of a new species of limited forever wars that would continue to serve as proxies in the decades to come for the direct great-power clashes that the atomic bomb had rendered unthinkable. Finally, on July 27, 1953, the two sides agreed to a truce that did nothing more than restore the pre-war status quo. By then, the Americans had lost 33,000 people in all, the South Koreans 415,000. Casualty figures for the North Koreans and Chinese are not so easy to come by, but a credible estimate lies in the neighborhood of 1.5 million between the two of them.

In the United States, the Korean War is often called the “forgotten war” today, being remembered if at all as the inauspicious start of a still-ongoing era of similarly inconclusive, unsatisfying conflicts that lack both the clear sense of purpose and the clear-cut winners and losers of the Second World War. By contrast, and despite the fact that it so literally accomplished nothing in tangible terms, Chairman Mao and the Communist governments of China that followed him have always loudly celebrated it as “The War to Resist American Aggression and Aid North Korea.” Mao especially had good reason to feel fondly toward the war, for it did much to cement his status as China’s one true leader, both domestically and internationally. In doing so, it set in place the final conditions necessary for what would become the most pernicious cult of personality of the latter twentieth century.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Peter Olausson

A superb text. Knew next to nothing about Taiwan’s past; it’s quite rich to read how it went from a third rate province to a purported crown jewel worth a major war. And “Chinese volunteers” could be seen as the 1950s equivalent to a special military operation …

Ajax

I enjoyed reading this article, but found some issues in the section on the Taiwanese history.

Firstly, Indigenous people have been living on Taiwan for thousands of years, including in settled villages.

Secondly, it’s a bit inaccurate to describe the island as a European colony; the Dutch and Spanish controlled relatively small areas around Tainan and Keelung/Tamsui.

Third, the Dutch weren’t driven away by a Chinese uprising; the Ming loyalist Koxinga (aka Zheng Chenggong) invaded and set up his own kingdom.

Fourth, the paragraph about Qing dynasty Taiwan presents it as a dangerous backwater. This isn’t entirely wrong – e.g. the Rover incident and the American Formosa Expedition in revenge, or even the Musha Incident in the 30s – but by the late 19th century some of the island was urbanized and developing its own middle class and intelligentsia; these were developed enough to proclaim an independent Republic of Formosa in 1895. I think Kerr crediting Japan with introducing law and order is a little unreliable here.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks for this. I made some edits and excised the quote from George Kerr, which were a bit of a ramble anyway.

Ajax

Thanks, that section looks a lot better now!

Leo Vellés

Another super interesting article Jimmy. One minor correction: “Now he was prepared to to meet them face to face on the field of battle…”. A double “to” there.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!