Few topics better illustrate the chasm between scholarly and populist history in China than does the decline and fall of the Han dynasty and the period that immediately followed it. For the scholars, it stands as an inauspicious time of chaos and civic deterioration, when the beneficence of the preceding centuries of imperial rule was squandered in pointless internecine warfare. For the proverbial Chinese person on the street, however, the period stands among the most exciting in all the country’s history. Even the dramatic rise and fall of the Qin dynasty has difficulty competing with the third century AD in the populist imagination.

The era owes its special status almost entirely to a single work of literature: the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong, which was written more than 1000 years after the events it describes, but which was based upon much older folk tales and chronicles. Since its first publication circa 1320, Romance of the Three Kingdoms has become China’s national epic — its nearest equivalent to the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Aeneid, the tales of Roland, or the stories of King Arthur and his knights. It remains the fodder of countless mass-media adaptations, from movies to television shows to a long-running series of videogames — ironically developed in Japan rather than China — that has made it very familiar to a certain segment of Westerners as well. One of its earliest scenes, in which the heroes Liu Bei, Zhang Fei, and Guan Yu swear an oath of allegiance to one another in a grove of peach trees, is arguably the most famous in all of Chinese literature, as much a touchstone for the modern Communist state as it was for China’s late imperial incarnations.

“There is a peach garden at the back of my farm,” said Zhang Fei. “The flowers are in full bloom at the moment. Let us institute a sacrificial offering and swear brotherhood and unity of hearts and mind before Heaven and Earth. Only thus can we embark upon our great mission.”

“That is just what we think,” agreed the other two.

So the next day, an altar was set up in the garden and sacrifices including a black ox, a white horse, and other things were prepared. Beneath the smoke of the burning incense, they knelt down and declared a solemn oath.

“We three, Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei, though of different families, swear brotherhood and mutual help to one end. From now on, we will aid each other in difficulty and rescue each other in danger. We will serve the country and protect the people. We ask not the same day of birth but we are willing to die at the same time. May Heaven, the all-powerful, and Earth, the ever bountiful, read our hearts! If we break our oath or betray each other’s trust, may Heaven and man smite us!”

Taken strictly on its own merits, Romance of the Three Kingdoms is without question a classic of world literature. It is also a remarkably readable book even in English when given a good translation, being full of enough flashing swords and devious conspiracies for any fan of Dumas, alongside enough wit and tragedy for a Shakespeare aficionado. It isn’t at all hard to understand why so many generations of Chinese have loved it so. I can heartily recommend it to you as a book well worth reading for the sheer pleasure of it after you finish this one. And it isn’t without value as history either.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms tells us that the factors which precipitated the Han dynasty’s decline were the same as those which brought about the downfall of many other Chinese dynasties. Rampant corruption and mismanagement caused the people to lose faith in their Son of Heaven, and eventually to conclude that he had lost the Mandate of Heaven. Both the novel and the older sources on which it is based place most of the blame for this squarely on the shoulders of the palace eunuchs, who, they say, marginalized the Confucian mandarins and made the emperor a virtual prisoner in his own home, even as they enriched themselves through onerous taxes and squashed like a bug any citizen who dared to question them. This too is a story beat that occurs again and again in Chinese historiography. In the traditional sources, the eunuchs at court are consistently associated with decline and dissolution, and the times when they enjoy considerable power are marked by those same qualities in the body politic as a whole. There is ample reason to view these narratives with a healthy degree of skepticism. We must remember that most Chinese works of history prior to the twentieth century were written by Confucianists, and reflect the contemporary agendas of their authors, who were more often than not at cross-purposes to the eunuchs in the eternal debate over who got to set the direction of the Chinese state. “In China,” notes Julia Lovell, “writing history has always been a political business.” (The same could of course be said of writing history in most places and times.)

But for whatever reason, China did gradually descend into civil strife, then into outright civil war. The three kingdoms of the novel’s title are those into which Inner China was divided after the final collapse of the Han dynasty in 220: Wei, Wu, and Shu. In the page of Luo Guanzhong’s book, their struggles against one another are as intricate and exciting as a good game of chess (a game which may very well have been invented in China during this period or earlier, as it happens). In reality, the old Chinese adage that living in “interesting times” is a curse which the wisest among us fervently wish to escape undoubtedly applied.

When Romance of the Three Kingdoms ends in about 280, a new would-be emperor of all of China has just taken over the kingdom of Wei, which contains within its territory all of the imperial capitals of the earlier dynasties — a hopeful sign! But the novel’s concluding note of optimism is ill-founded. This would-be new dynasty for all of China, which was known as the Jin, never lived up to the legacy of the Han; it never succeeded in bringing that part of Inner China outside the borders of Wei to heel for any length of time. Instead the tripartite division of the land of the Three Kingdoms period was replaced by yet more extreme fragmentation, as China splintered into ever more and smaller states.

Thus the next three centuries have gone down in history not as the era of the Jin but as a continuation of a long interregnum in the rule of Huang emperors. In the midst of this fractious period, many a person must have wondered whether the four and a half centuries of the Qin and Han dynasties had been the real historical aberration, whether China would ever be properly united again.

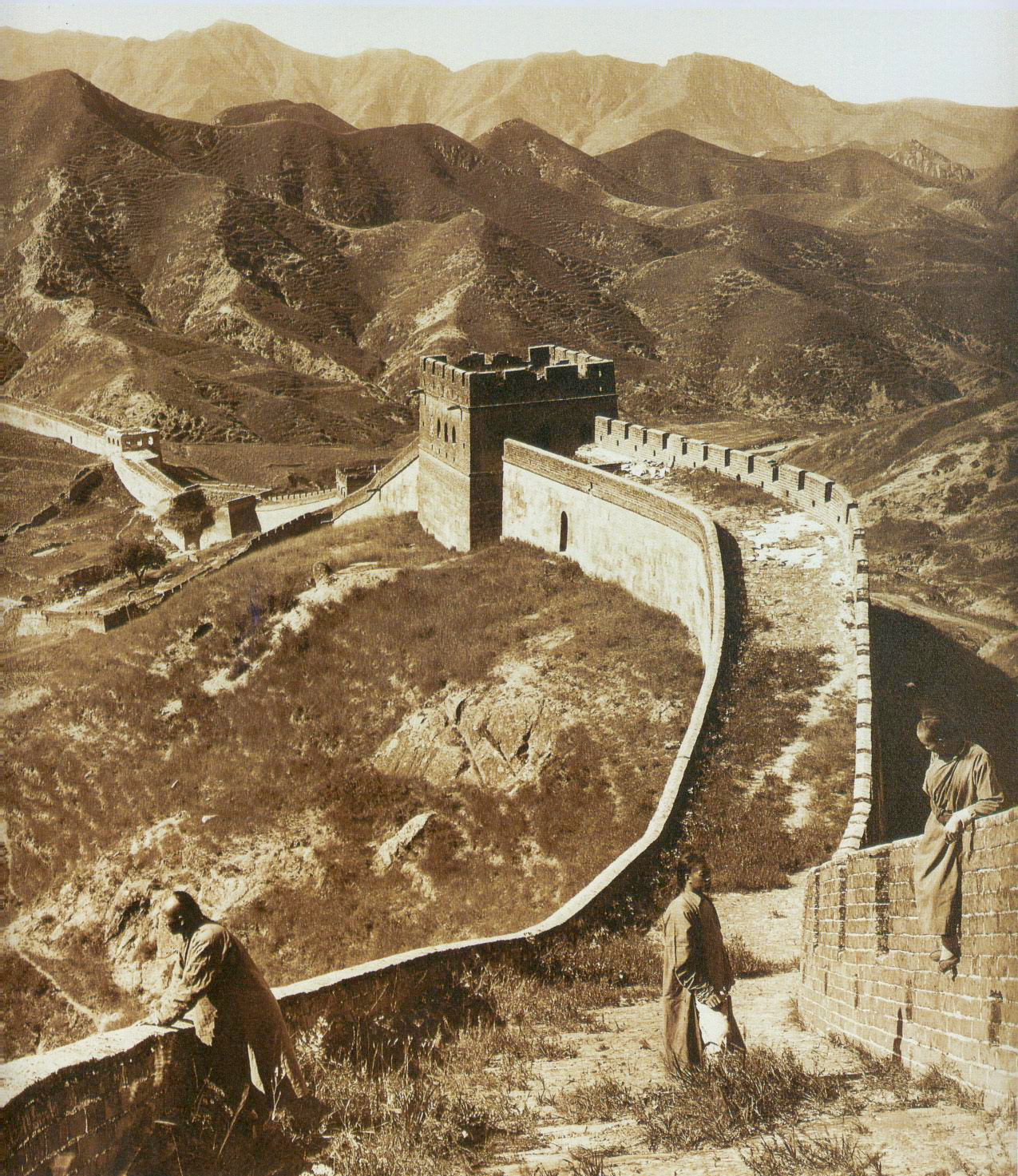

China’s weakness was always the strength of those who lived outside the Great Wall. The Han dynasty had kept the Xiongnu and their like at bay, at times through tribute payments, at times by deploying armies of its own. But the feeble Jin emperors had neither the wealth nor the military wherewithal to follow suit. Thus by the beginning of the fourth century, outsiders were roaming Northern Inner China with impunity, raiding wherever and whenever they liked. In 311, a Xiongnu army sacked Luoyang, seat of both the Jin and Han dynasties. With a population of 600,000 people, Luoyang was at this time the largest city in all of China. The impact of this humiliation on the Chinese public psyche was comparable to that of the first sacking of Rome on the Western view of self 99 years later. The unthinkable had been allowed to happen; the whole world seemed out of joint. “Ever since the powerful barbarians unleashed violence, China has fallen into chaos,” wrote one scribe. “The people have become desperate and dispossessed.” The tidy order of imperial life seemed irrevocably spoiled: “The rivers were filled with floating corpses. Bleached bones covered the fields.” It was only the beginning; between 304 and 439, no fewer than sixteen separate foreign kingdoms were established in Northern Inner China.

The crisis greatly increased the popularity of Buddhism; that religion’s philosophy of withdrawal from worldly things has always struck people as most appealing when the world around them has little solace to offer them anyway. Meanwhile Northern Han Chinese of a more pragmatic bent fled in large numbers to the South, which was protected from the barbarian incursions by the Qinling Mountains and the watery, swampy landscape beyond, barriers more effective than any human-made Great Wall had ever been.

Culture clash was the inevitable result of the sudden influx of Northerners in the South. This prissy Northerner’s harangue against his hosts, “companions of fish and turtles,” is hilariously typical.

The South enjoys a respite of peace in their remote corner, where it is hot and humid, crawling with insects, and infected with malaria. Like frogs and toads sharing the same hole, people live together with the birds. Your rulers wear their hair short and never have long heads. The people decorate their bodies. You float on the three rivers or row in the five lakes, but have never been steeped in music or reformed by laws. Even though some Qin and Han convicts brought the true Chinese pronunciation, the unpleasant tongues have not been transformed. You may have a ruler and a court, but the ruler is overbearing and his subordinates violent. For instance, first Lio Shao murdered his father, then Xiulung committed incest with his mother. To commit such breaches of morality makes you no better than birds and beasts. On top of this, the princess of Shanyin asked to buy husbands to commit debauchery, caring nothing about how people ridiculed her. You, sirs, are still soaked in the old customs, and have not yet been transformed by ritual. You can be compared to the people of Yangdi who did not realize that goiters were ugly.

It must have seemed to many such a bewildered refugee that the part of China north of the Qinling Mountains was lost forever to the barbarian hordes. In the end, though, a phenomenon almost unique to Chinese history asserted itself. Instead of remaking China, the foreigners who started kingdoms in Northern Inner China were themselves remade by the people they had ostensibly conquered.

In the beginning, much of the invaders’ transformation was driven strictly by practicalities. These steppe nomads had no knowledge of farming, no experience ruling over a sedentary populace. They found that the draconian approach only got them so far; at some point, they had to learn to husband the land and administrate the society that worked it. They had only one source of help for doing so: the very same mandarins who had been running things prior to their arrival. As these latter penetrated the ranks of their overlords, their values seeped in as well, until after some decades the conquered had remade their conquerors in their own image. By the fifth century AD, the kings of several erstwhile barbarian states of Northern Inner China were actively vying — albeit none of them ultimately any more successfully than the Jin dynasty — to claim the Mandate of Heaven and crown themselves the Chinese emperor. “Our home was originally desert and steppe, and we were barbarians,” confessed one of them with affected Confucian humility. “With such a background, how could I dare place myself in the distinguished line of Chinese emperors?” Now, however, things had changed. Northern Inner China would remain Chinese after all, not through any instrument so crude as counterrevolution but through slow, subtle assimilation. “With time and patience, the mulberry leaf becomes a silk gown,” runs a Chinese proverb.

Speaking of which: the Silk Road, that slender thread binding East and West, continued to exist throughout this era of division. If anything, the trade may have increased after the more easterly city of Constantinople replaced Rome as the supreme capital of Western civilization during the fourth century. But it is unclear whether any traders even at this stage made the full journey of some 4000 miles (6500 kilometers) between Constantinople and Inner China. It would seem that the vast majority of the trade at the very least still passed through the hands of middlemen, especially those who lived in the sprawling Persian Empire that lay in between the Byzantine Empire and China. Still, unlike the Romans the Byzantines did have a settled name for China: Serinda, which is derived from the Latin word for silk.

Even in the absence of a strong central government, the Chinese guarded the age-old techniques of silk weaving, as well as the silkworms themselves and the mulberry plants upon which they fed, with all the care with which any modern corporation guards its most precious trade secrets. Nevertheless, in about 552 some enterprising Byzantine monks smuggled all three back to their homeland. A Byzantine chronicle claims that they hollowed out their walking sticks and hid some stolen silkworms there. Then they prevailed upon their Chinese hosts to give them a few small mulberry plants; the Chinese agreed to do so on the assumption that the monks would never be able to keep the plants alive on the long trek through the Gobi Desert. But this feat they somehow managed to accomplish, finding ways of watering them even when it meant that they themselves had to go thirsty.

Constantinople began to produce silk of its own shortly thereafter. The trade quickly became a major profit center for this increasingly beleaguered heir to the glory that was Rome, reckoning as it was with the rise of Islam on its eastern and southern flanks among other pressures. By contrast, the theft was of little real economic importance to China. The relative trickle of silk that continued to reach the West from the East was still prized for its rarity and its supposedly better quality in comparison to the homegrown stuff. So, the Silk Road remained what it had always been: a trade in luxurious exotica for the well-heeled set.

Some historians have made much of the parallels they notice between the East and the West during this time period. Most famously, Frederick John Teggart published in 1939 a briefly influential book called Rome and China: A Study of Correlations in Historical Events, whose thesis is that the collapse of the Han dynasty and the slower decline and fall of Rome were both precipitated by the peoples who lived in between them. After all, Teggart observes, both China and Rome suffered the humiliation of seeing their capitals sacked by nomadic barbarians; surely this means something. But his book is better at describing correlation than causation, and few historians give it much credence today. While it is true that China entered its own period of chaos and decline at roughly the same time as the Mediterranean world, it proved better at turning collapse into renewal; China’s cultural ebb tide lasted a comparatively brief four centuries. And then, while the West was just hunkering down in earnest for its long Middle Ages, Chinese civilization flowed forth again in torrential fashion to begin its most glorious period yet.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

morg

> “In China,” notes Julia Lowell, “writing history has always been a political business.”

That’s Julia Lovell with a V, and once again it ain’t just China that applies to — any historian who claims to be above politics is trying to sell you their own 🙂

Also I think that’s more properly “administer” in “properly administrate the society”?

Jimmy Maher

Thanks! “Administrate” and “administer” are interchangeable here. I prefer the former, but strictly for aesthetic reasons that I can’t really explain.

Aula

“both the Jin dynasty and Han dynasties”

This should have either “dynasty” twice or “dynasties” once.

“a phenomenon almost unique to Chinese history”

But not completely unique; the same thing happened with the Varangian conquest of the Rus.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Richard Smith

Please do not use the outdated term “The Dark Ages” for a complex 1000 years of European history. It carries connotations that simply aren’t true for the whole period.

Jimmy Maher

Fair enough. Thanks!