Revolutions come with a poison pill attached: any wholly successful one is doomed to the tiresome fate of becoming the status quo. This is as true of aesthetic revolutions as it is of political ones. The very fact that we Moderns so readily recognize, understand, and respond to the overall aesthetic of Renaissance art can cause us to undervalue how radically new it was in its own time. Therefore it might be best for us to begin our examination of it by looking at the Medieval art which came before it, which is vastly more alien to our sensibilities.

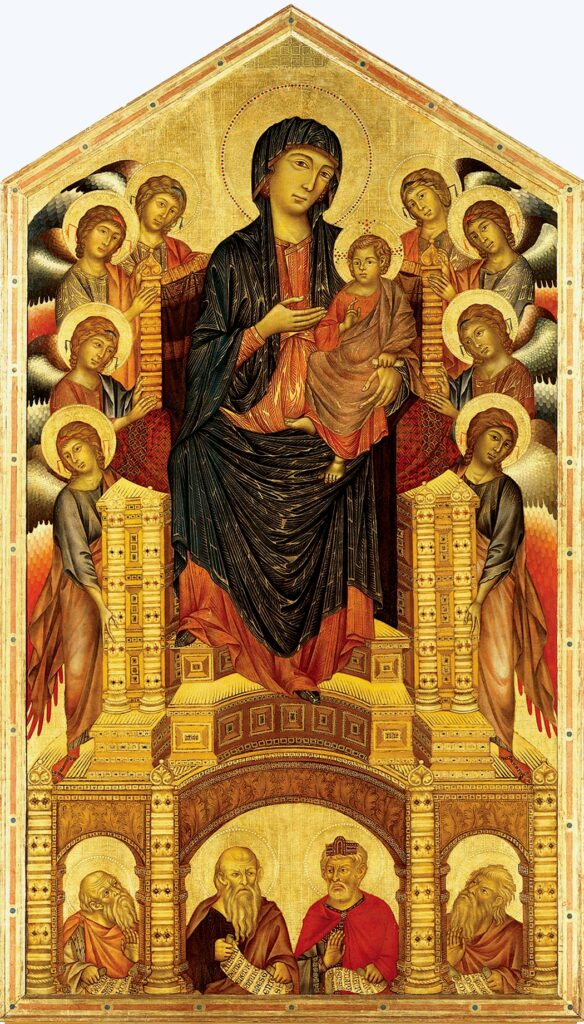

Let us take as our example the Madonna and Child by Cimabue, a Florentine master of the High Medieval style. He painted this work around the year 1295 for Santa Trinita, a church that still stands in Florence.

To our eyes, the painting has an almost childlike quality about it. The crude round halos around the figures’ heads seem rather banal. And when we look closer at the faces, we realize that they are all the exact same face. The effect is actually rather creepy; even the male prophets at the bottom of the scene — even the baby Jesus himself in his mother’s arms — have the same basic features as Mary and her retinue of angels. The people look more like butterflies pinned to a board for our inspection than living specimens. Even their clothing is rigid and generic, the folds all occurring in the exact same places.

Further, the staging of the scene is confusing to the eye. The four prophets seem to be staring out as us from a sort of mezzanine deck, with a giant Mary and Jesus perched above them. Everyone is out of proportion with everyone else. Only gradually might it begin to dawn on us that the painter is not really trying to stack the figures incongruously on top of one another, that the prophets at the bottom of the frame are supposed to be in front of Mary and Jesus. The artist is halfheartedly trying to convey depth, but the effect is so unconvincing to those of us who are used to peering at photo-realistic imagery on our screens all day that at first we don’t even realize that any attempt at all is being made.

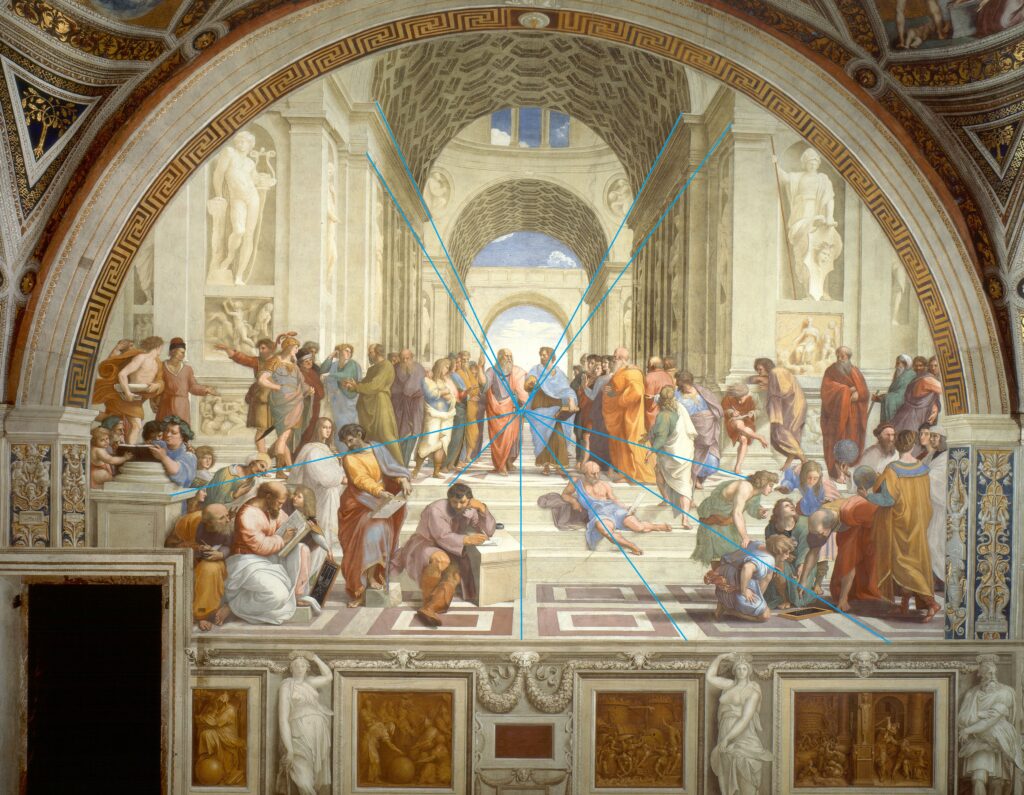

Now, let us leap forward two centuries to one of the acknowledged masterpieces of the late Renaissance: The School of Athens, painted by Raphael in 1511 for the pope’s residence in Rome.

Notice how much livelier and more fluid this scene is. Gone are the clones with the crude halos. Every figure here is an individual, with his own facial features, build, posture, and clothing, doing something unique to himself. Notice the extraordinary sense of dimension and depth the painting conveys; we feel as if we could walk right into it. And then, too, consider the subject matter: this is not a scene from the Bible, even though it was painted for the pope. While plenty of Renaissance art did still depict Christian subjects and was often hung in churches, it was no longer unthinkable after the fourteenth century to paint pseudo-historical pastiches like this one, or scenes drawn from pagan mythology, or even portraits of living individuals.

How did we get from Madonna and Child to The School of Athens? It’s obvious that the techniques of painting made tremendous strides in the intervening 215 years, but that is in some ways the less important part of the story. Before artistic techniques could improve, the will to improve them had to exist. More so even than a paucity of technique, the unnatural, uncomfortable-looking poses of Cimabue’s Madonna and Child reflect the Middle Ages’ profound discomfort with the human body and all other earthly matters. But, as we have been learning, such attitudes began to shift after the time of Saint Thomas Aquinas, opening up new vistas for the visual arts just as it did for the literary ones; Cimabue would prove one of the last of the indelibly Medieval masters.

The visual arts’ nearest equivalent to Petrarch, in the sense of being the harbinger of the burgeoning new sensibility, was a Florentine painter named Giotto, who lived from 1267 to 1337, a span that overlapped the lives of Cimabue before him and Petrarch after him.

A work like Giotto’s 1305 fresco The Kiss of Judas, showing the untrustworthy apostle in the act of signaling Jesus’s identity to the Roman authorities by ostentatiously embracing him, still sports many of the attributes of Medieval art, such as the halos around the heads of Jesus and his loyal followers. At the same time, however, the scene is surprisingly dynamic, lacking the rigid, posed quality of the Madonna and Child. It likewise reflects more of a desire to differentiate its individual characters and to convey a sense of depth, even if it isn’t entirely successful in either respect.

Nevertheless, it was a brilliant start. Small wonder that Giotto was revered by the Renaissance artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as the first painter who was, in sensibility if not in the sophistication of his technique, more or less like them.

Once the will to create more believable pictures of life was there, it was just a matter of discovering the ways. The chief stumbling block was the problem of perspective — i.e., the problem of portraying a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, which had been previously solved among all the world’s artists only by the Greeks and Romans of Antiquity, and then only partially. The artists of ancient Egypt, of China, of the Muslim world… all had been defeated by it. Giotto and other European masters who came after him also did their best, but their scenes still look noticeably off to the viewer.

The man who finally devised a workable solution to the problem is ironically far more famous today as an architect than a painter. Filippo Brunelleschi was born in Florence in 1377, and was already a well-known sculptor and architect in his hometown when he began to study the problem of perspective in earnest circa 1410. Being deeply immersed in the new spirit of humanistic inquiry that had come so to mark life in Florence, he grasped that only a rigorous, empirically focused approach would allow him to succeed where so many others had failed. Accordingly, he started by peering hard at the three-dimensional world that lay all around him, asking himself what it was that conveyed its depth to his eyes and how he might duplicate that something inside a picture frame.

Brunelleschi was the first person since Antiquity to observe and articulate the phenomenon of the vanishing point. Imagine yourself standing on a railroad track and staring at it as it recedes into the distance along a perfectly level plain. The two rails will seem to get closer and closer together with increasing distance, until they disappear just as they are about to merge into one. The place where they do so is the vanishing point. In a painting, it is the locus toward which an imaginary viewer of the real-life scene being depicted has directed her eyes. Once you have a vanishing point, you can create a believable impression of three-dimensional space by making the straight lines in your picture converge toward that single point, just like the two rails of our imagined track. Painters and drawers now refer to this technique as one-point perspective.

Look again at Raphael’s School of Athens, which has become literally a textbook illustration of one-point perspective in action. The vanishing point on which our imaginary observer’s eyes are focused is Plato’s left hand — or rather a point behind his hand, if we could see it. Notice how everything else converges toward that point. This is the reason that the painting as a whole looks like a scene into which we could step bodily. (The effect is subtly enhanced by the arch-like shape of the fresco, duplicating the archways of the painted interior.) In addition to being an aesthetic masterpiece, The School of Athens is a technical tour de force. And it was the architect Brunelleschi who first laid out a century before its creation the technique it shows off to such splendid effect.

Brunelleschi promoted his discovery of the vanishing point with a parlor trick that became the talk of Florence. He painted a meticulously exact duplicate of the Baptistery of San Giovanni, a Florentine landmark, from a viewpoint outside of its central arch, peering down its nave. (Hallway-like configurations such as a church nave are ideal for paintings that use one-point perspective because their walls act much like our aforementioned railroad tracks, providing a perfect visual cue.) But in the place where the sky ought to have been in his painting, Brunelleschi instead pasted strips of burnished silver that acted like a mirror. Then he poked a hole through the precise center of the canvas, a location which coincided with his picture’s vanishing point.

Brunelleschi took test subjects to the place in front of the real baptistery from which it was portrayed in the painting, and asked them to view the scene by holding the back side of the painting up to their faces and peering with one eye through the hole. Now, Brunelleschi, standing just so, raised a mirror up in front of his guinea pig, so that it blocked her view of the real baptistery, reflecting instead his painted version of it back toward her. Everyone was amazed to find that the painted scene was almost indistinguishable from the real one. The burnished silver sky of the painting was the pièce de résistance: the doubled reflection revealed a view of the real sky, so that the painting too appeared to have an animated heavens, complete with clouds drifting past and birds flying about.

Brunelleschi’s painting of the Baptistery of San Giovanni has long since been lost; it was reported to be in the hands of the Medici family as late as the 1490s, but it disappears from the record after that point. Lacking proof in the form of a physical artifact, some scholars have questioned whether the demonstration I’ve just described ever really took place at all. Yet there was such a buzz around Brunelleschi and perspective in Florence by the 1420s that one simply has to assume that there was some good, obvious reason for it. Almost every time Brunelleschi’s name was mentioned in Florence over a span of some fifteen years, it was prefixed by his new title of “master of perspective.” His modern biographer Paul Robert Walker is just as fulsome as his contemporaries were:

Not a single authenticated drawing in Filippo’s hand has survived, and yet the mark of that hand can be found in every realistic painting since the third decade of the Quattrocento [the fifteenth century]. It is no exaggeration to say that without Brunelleschi’s formulation of perspective, there would have been no Renaissance in painting at the time and place that it occurred. And there would have been no painting Renaissance at all until someone else discovered what Filippo discovered.

The irony in this is, Walker hastens to add, that “he was never a painter professionally, and he never wanted to be a painter.”

For, as previously mentioned, Brunelleschi was primarily a sculptor and, most famously of all, an architect. Far from being an obstacle, it may very well have been his habit of working in those intrinsically three-dimensional disciplines that allowed him to think differently from the painters of his day. He left it to a friend named Leon Battista Alberti to publish a rigorous description of his new technique for painting in a 1435 treatise entitled simply On Painting, which became, as Paul Robert Walker puts it, “the fundamental text of Renaissance art.”

Even in the time of Brunelleschi and Alberti, it was recognized that one-point perspective has its limitations, being best suited for depicting relatively symmetrical scenes. Messier, more complex scenes require more complex techniques to bring off. And such techniques would be invented in due course; the German painter Albrecht Dürer would start to experiment with two-point perspective already by 1525. Still, it was Brunelleschi and Alberti who opened the floodgates, transforming the art of painting forever with the new sense of possibilities they introduced. Luckily, the Renaissance artists of Florence were obsessed with harmony and proportion anyway, leaving them with a natural proclivity to paint scenes that were perfect for the prescriptions of one-point perspective.

Meanwhile, not content with transforming the art of painting forever, Brunelleschi returned to his first love of architecture, spending most of the 1420s and 1430s laboring over his masterpiece, the octagonal dome of Florence Cathedral, an awe-inspiring achievement by any measure. Like so much in Florence at the time, it was intended as a concrete manifestation of the new ways of life and thought. “Cursed be the man who invented this wretched Gothic architecture!” wrote Brunelleschi’s colleague Antonio Filarete in 1450, referring to the oppressive weightiness of the High Medieval architectural aesthetic, as embodied in landmarks like Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral. “Only a barbarous people could have brought it to Italy.”

Brunelleschi’s dome was nothing like that; despite its immense size and weight, it looked somehow light, almost playfully lovely, a happy tribute to a God who was as comfortable on Earth as he was in Heaven. It was an astonishing feat of engineering as well as artistry, being completely free-standing, with no buttresses whatsoever; Brunelleschi liked to compare the delicate balancing of forces that was required for its construction to making an egg stand on end on its own. It remains to this day the largest single masonry dome ever made. “Of Filippo Brunelleschi,” wrote Giorgio Vasari, the author of a history of Renaissance art that was published in 1550, “it may be said that he was given by heaven to invest architecture with new forms, after it had wandered astray for many centuries.” His dome became the symbol of Florence, dominating its skyline during the later Renaissance as it still does today, looking down on the hustle and bustle of a city great in vision and energy if not in sheer size.

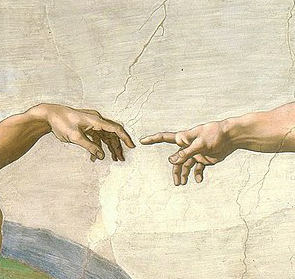

Indeed, Brunelleschi’s dome is a fine symbol of the Renaissance itself in many ways. The techniques that permitted its construction were the early fruits of the return to empirical experimentation and logic. Science and art became one another’s companions during the Renaissance to a degree seldom seen elsewhere in history. Artists, for example, studied and sometimes even dissected the human body as assiduously as medical doctors in order to capture its musculature as accurately as possible. This work, combined with the newfound sense of permissiveness amongst the culture that surrounded the artists, led to the triumphant return of the nude human form, which had been absent from the visual arts for the better part of a millennium.

Renaissance artists were very conscious of their revolutionary agenda, as were their patrons, hangers-on, and chroniclers. One might go so far as to claim that Renaissance art was the first concerted, self-directed artistic movement in history, coming complete with its own ideology and aesthetic values.

By the time of Brunelleschi’s death in 1446, Renaissance Florence was in full flower. Cosimo de’ Medici’s goal of making his city the host of one of the golden ages of the human mind and spirit, on a level with ancient Athens or Alexandria, had become a reality. “The Florentine attitude toward Antiquity was the same as towards popes and princes,” writes Mary McCarthy. “The Florentines felt themselves to be the equals of the ancients and were on democratic terms with them.” A philosopher named Marsilio Ficino established a Platonic Academy in Florence, modeled on the legendary Lyceum of Aristotle. Here gathered the best and the brightest from throughout Italy and the rest of Europe, to argue and refine their ideas in the oral tradition of the ancients. Among their ranks were people like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who in his brief 31 years on Earth learned to speak more than twenty languages and became the first writer to have his printed works banned by the Inquisition for their aggressive, provocative humanism, which led the conservative wings of the Church to brand them heresy and has led more recent scholars to call them the “Manifesto of the Renaissance.”

Also on the scene was a name that rings much more familiarly to our ears: Niccolò Machiavelli, the most famous — or perhaps infamous — political philosopher in all of history. His treatise The Prince, history’s ultimate explication of ends justifying means, can be read as either a description of politics as they are generally practiced or as a prescription for effective tyranny. Either way, his cynical realpolitik might at first seem at odds with the other, more idealistic aspects of Renaissance Florentine life which he have been meeting of late. As we’ll see in the next chapter, though, the city’s own internal politics, not to mention those of the continent of which it was becoming such an influential part, would continue to do much to justify Machiavelli’s cynicism.

Nevertheless, both outside the realm of politics and often within it, the city’s passion for art as a worthy end unto itself was as real and powerful as it has been in any time and place in human history. Before the Renaissance, artists had aspired to be craftsmen rather than geniuses. Virtually the entirety of Medieval art was religious art, serving to glorify not the person or people who made it but rather God, the church in which it was housed, and/or the wealthy patron who commissioned it. It is partially for this reason that we simply don’t know who made some of the finest pieces of the Middle Ages; the practice of an artist “signing” his work emerged only with the Renaissance. Renaissance artists too claimed to a veritable person to be working for the glory of God, and we have no reason to doubt the sincerity of this claim. But a goodly share of the glory also reflected back on them, and we have no reason to doubt that they enormously enjoyed and appreciated this as well. This shift in perspective would prove as important in its way as the purely painterly one inculcated by Filippo Brunelleschi; it may not be going too far to say that the entirety of Modern “museum culture” springs from it.

For it was Renaissance Florence that invented the cult of the artist as a creature of a higher plane, to one extent or another exempt from the duties and strictures of everyday humanity. Art was huge in Florence, and those privileged and accomplished enough to create it were the rock stars of their era. Their feuds and friendships, their antics and diversions and love affairs were the talk of the town.

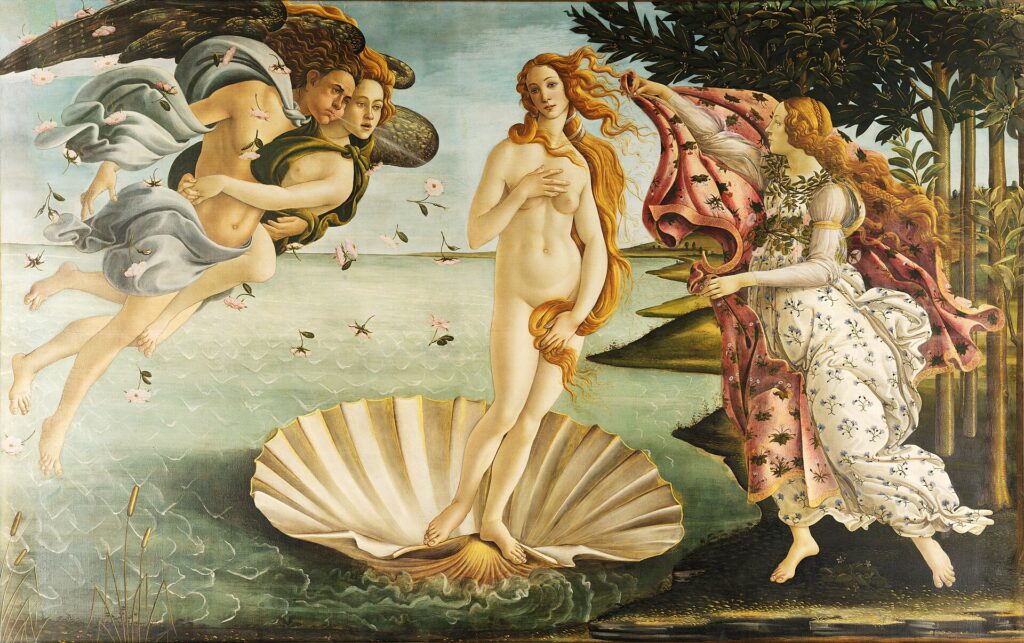

The rock star among rock stars in late-fifteenth-century Florence was Sandro Botticelli, who was renowned — or, in some circles, scorned — as much for his lifestyle as for his beautiful, sensuous paintings. Giorgio Vasari describes him as “a merry fellow” who was the life of any party he happened to attend, whilst admitting that he “squandered and wasted” the huge sums of money he earned, what with his “customarily haphazard existence.” It was Botticelli more than anyone else who made nudity such a fixture of Renaissance art, much to the delight of the epicurean upper crust of Florence whose houses his paintings decorated. Florentine gossip had it that he had learned to portray the female body so believably through many hours of personal exploration of real ones, both high- and low-born. And some said that his interests in this area extended equally to the males of his species.

Botticelli might well have had a challenger for primacy in Leonardo da Vinci, that prototypical Renaissance Man, who was as interested in experimenting with flying machines and the like as he was in creating beautiful art. But Leonardo left Florence for Milan when he was 30 years old. He spent long stretches of time thereafter in that rival Italian city-state, as well as in Rome and in France near the end of his life, somewhat diluting his reputation as an indubitably Florentine figure. The comparatively small number of artistic works he managed to complete, what with his many other interests, likewise prevented him from becoming as towering a figure in Florence as Botticelli. In some ways, he is better known in our time than he was in his own. Which isn’t to say that he wasn’t highly respected, of course.

But as celebrated and sometimes controversial as men like Botticelli and Leonardo were, the real prime mover of Florentine artistry was the Medici family, who remained the supreme masters of the city from 1434 to 1492. They were Florence’s royal family in all but name, passing their rule down through three generations over that span of time: from Cosimo de’ Medici to his sickly son Piero in 1464, thence to Piero’s own much more charismatic son Lorenzo in 1469. They had control of public commissions all over the city, as well as their own opulent private properties to decorate. An invitation to the Medici palace was the hot ticket that every artist or aspiring artist dreamed of; if they deemed some up-and-comer to be a true prodigy, they might pay for him to set up his own studio, then be the first in line to buy what he produced. As the preeminent taste-makers of the era, the family’s imprimatur could make an artist for life. And, needless to say, the opposite applied as well.

The Medicis frequently put on contests for the right to decorate the city’s public spaces, from its churches to its parks. These became the reality shows of their day, setting up rivalries among artists that in some cases became lifelong. And that was just fine with the Medicis and the rest of the Florentines, who evinced a thoroughly Italian love of interpersonal drama amidst all of their loftier aesthetic aspirations.

By way of summing up this revolution in perspective, in all of its different aspects, let us return to Giorgio Vasari, whose The Lives of the Artists is one of the seminal texts in the field of art history. A collection of capsule biographies of the most important Renaissance artists, self-consciously crafted in the mold of the ancient Roman biographer Plutarch, it can be credited with popularizing throughout Europe the Florentine notion of the artist as a rarefied being distinct from his more plebeian kith and kin. In his preface, Vasari applies the same arc to the history of art that Petrarch had previously applied to the life of the mind more generally: that of a long Dark Ages that followed the heady heights of Antiquity, an extended sleep from which humanity had just recently awakened.

With Rome’s fall the most excellent craftsmen, sculptors, painters, and architects were likewise destroyed, leaving their crafts and their very persons buried and submerged under the miserable ruins and the disasters which befell that most illustrious city. Painting and sculpture were the first to go to ruin, since they are arts that serve more to delight us than anything else. And the other one — that is, architecture — since it was necessary and useful to the welfare of the body, continued, but no longer in its former perfection and goodness. Had it not been for the fact that painting and sculpture represented to the eyes of those being born the men who one after another had been immortalized by their work, the very memory of one or the other of these arts would soon have been erased.

What was most infinitely harmful and damaging was the fervent zeal of the new Christian religion, which, after a long and bloody struggle, had finally overthrown and annihilated the ancient religion of the pagans by the number of its miracles and the sincerity of its actions. Then, with the greatest fervor and diligence, it applied itself to removing and eradicating on every side the slightest thing from which sin might arise. And not only did it ruin or cast to the ground all the marvelous statues, sculptures, paintings, mosaics, and ornaments of the false pagan gods, but it also did away with the memorials and testimonials to an infinite number of illustrious people, in whose honor statues and other memorials had been constructed in public places by the geniuses of Antiquity. Moreover, in order to build churches for public worship, not only did this religion destroy the most honored temples of the pagan idols, but, in order to ennoble and adorn Saint Peter’s [Basilica] with more ornaments than it originally possessed, it plundered the columns of stone on the Tomb of Hadrian, now called the Castel Sant’Angelo, as well as many other monuments which today we see in ruins. And although the Christian religion did not do such things out of any hatred for genius, but rather only to condemn and eradicate the gods of the pagans, the complete destruction of [the] honorable [artistic] professions, which lost their techniques entirely, was nevertheless the result of its ardent zeal.

The Florentines of the fifteenth century believed that they were putting a millennium of cultural stasis behind them. Humanity was marching boldly forward once again, with their city at the head. As we have seen, the real picture of progress or the lack thereof during the Middle Ages is more complicated than that. Yet in a sense that didn’t really matter; the mere belief that one is part of a better, brighter generation can become a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy.

In 1475, amidst this intoxicating atmosphere of cultural renewal, a second child was born to the mayor of Caprese, a village that lay within the territory of the Florentine Republic, about 40 miles (65 kilometers) as the crow flew from Florence itself. Like his future rival Raphael, who would be born eight years later, this baby was named after an archangel. His full name was Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, but soon enough no one would feel any need to state the extended suffix. He would become simply Michelangelo, the greatest single artist of the Renaissance — or, many would argue both then and now, of any other period of human history.

Did you enjoy this chapter? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Ilmari Jauhiainen

Great stuff! I just wondered about the source for the statement that Pico della Mirandola was suspected of atheism. The quotes from the pope’s bull I’ve seen speak broadly of heresy, which in those days could really mean just anything. The few scholarly works on the issue I’ve read suggest the church was more concerned about Pico dabbling with magic (he was interested of Kabbalah and other esoteric works).

Also, I am not sure if you are familiar with the icons of the Easten Orthodox Church. Even to this day, they usually have the very same qualities you pointed out as characteristic of mediaeval art, so that tradition of painting does live on.

Jimmy Maher

I was thinking specifically of Pico’s early phase as a committed Neoplatonist, when we went so far as to end gathering by saying “In Plato we trust” rather than “In God we trust.” But now I can’t seem to find that specific accusation of atheism laid out explicitly — although it did tend to be a fairly all-purpose accusation to be applied to thinkers the Church didn’t like. I’ve swapped “atheism” out for “heresy.” Thanks!

Yes, I have seen Eastern Orthodox art, although I don’t pretend to know much about it. I agree that it does have a resemblance to Western Medieval art.

Martin

While not even slightly a medieval art scholar, I remember hearing somewhere that the sizes of the characters in such paintings indicates the importance of them. Just by looking at the relative sizes of the characters, you should be able to tell who the artist (or patron or church) thought were the most important.

As to the angels all looking the same, do we actually know in the church’s view whether angels had similar or different faces?

Jimmy Maher

Yes, there was some of that going on as well in a painting like Madonna and Child.

I’m not sure that anyone in the Church had a firm view as to the facial features of angels. 😉 Outside of certain non-Christian styles of poetry, such an intense focus on the visual didn’t really exist in writing or in others forms of discourse prior to the advent of the novel. One might say that the Bible and most other pre-Modern Christian writings are the antithesis of the “show, don’t tell” philosophy; to attempt to *show* the ineffable could be considered an affront against God in itself. This is one of the things that gives Medieval art its oddly attenuated quality.

Ilmari Jauhiainen

Angelology was something debated a lot by the medieval philosophers. In time, it became the majority view that angels are immaterial creatures, so they wouldn’t really look like anything nor would the have any faces. Some philosophers thought they could still assume bodies, for the sake of communicating with humans, but they would be more what clothes are to us.

Ross

Not necessarily direct answer to the question, but I know Aquinas held that, because angels were immaterial, each angel was a species unto itself, since individual members of a species could only be differentiated by being made of separate bits of matter. And because each angel was a perfect exemplar of what it was supposed to be, each species of angel was also a genus unto itself, because species within a genus could only be differentiated in how they deviated from the platonic form of the “kind”.

Ilmari Jauhiainen

Then again, Aquinas’ position on the individuation of angels was highly controversial. Earlier theologians, if they even considered the question, had merely assumed that angels too had some sort of matter (often relying on Aristotle, wo had said that pretty much everything, beyond god, has both matter and form). After Aquinas’ death, his position on angels was condemned by the bishop of Paris , perhaps because it would restrict divine omnipotence, if many angels of same species could not be created. Later medieval theologians went then more to the direction that angels can be individuals at the same time as they are immaterial.

Will Moczarski

he have seen -> we have seen