It will presumably not come as a surprise to most readers that communism as it was actually practiced during the twentieth century diverged markedly from the communism described by Karl Marx in the nineteenth. One of the most vexing of the inconsistencies involved the types of societies in which communism took root. Marx stated explicitly and repeatedly that a nation must pass through a phase of capitalism and widespread industrialization before it could become communist. He warned that any attempt to jump the gun, even for the best of reasons — i.e., to avoid the widespread inequality and suffering that inevitably accompanied capitalism — could only result in a “primitive and crude social leveling” that would be as injurious to a country’s prospects of achieving true communism in the long term as it would be harmful to its population in the short term.

Yet the reality is that the people of no developed, industrialized country in history have ever spontaneously chosen to go communist of their own free will; it has only been imposed on such peoples by foreign invaders. Those nations which have achieved communism — in name, at any rate — through internal revolt have universally been agrarian, pre-industrial societies. Marx’s warning about “primitive and crude social leveling” seems shockingly prescient when considered in light of this, for communism as it was practiced in such countries was invariably brutal and, in most cases, ultimately catastrophic. Those old-school communist regimes which have managed to survive to the present day have done so by stepping back from the ideological brink and learning to accept a considerable degree of divergence between the precepts of communism and the way their countries really function. Meanwhile we continue to wait for utopian communism to take root and spread as Marx said it would, in a capitalist and industrialized society.

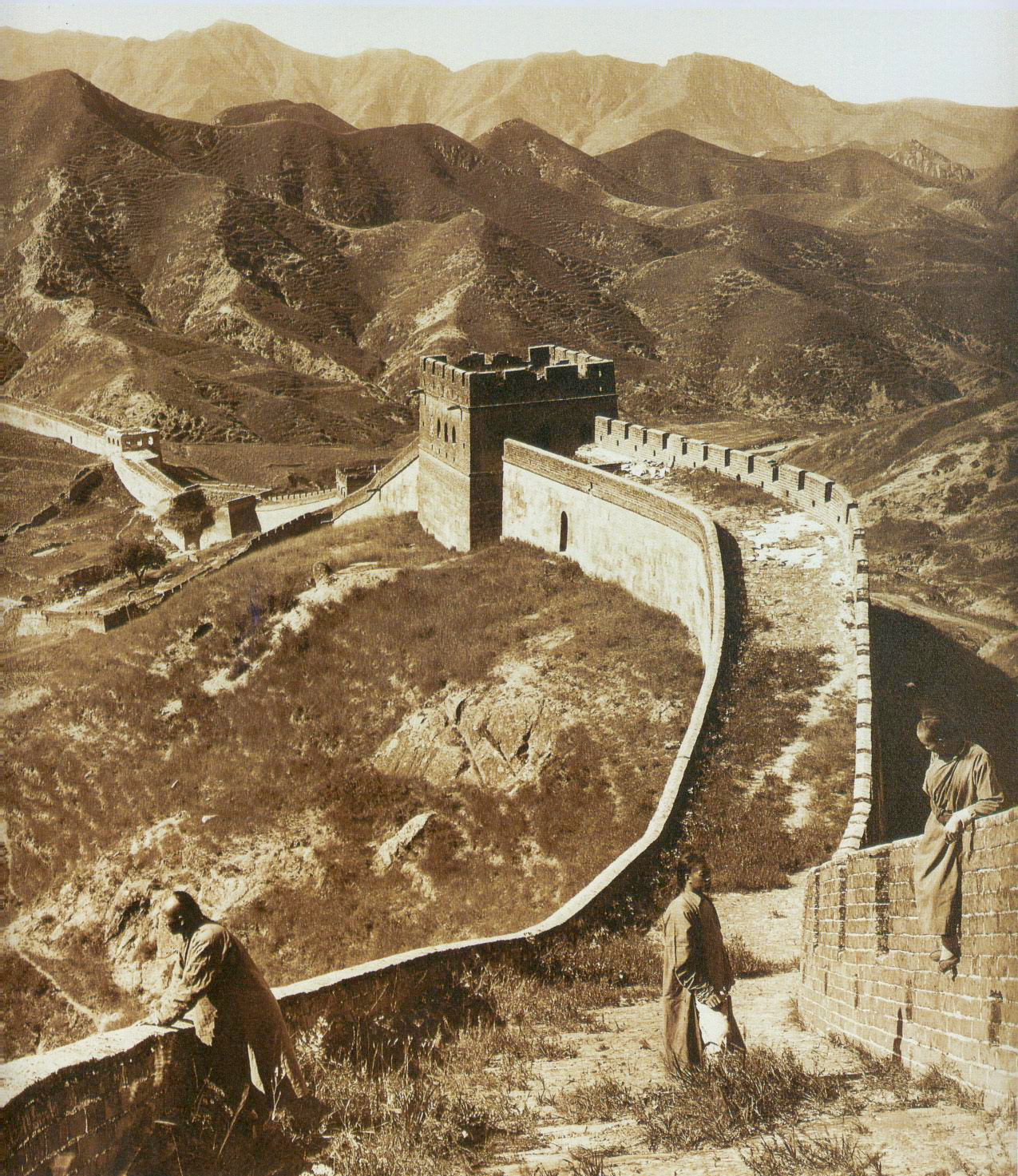

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, China has stood as the largest and most powerful self-avowedly communist nation in the world. Its relationship with ideology makes it a fascinating case study. As we saw in earlier chapters, imperial Chinese history can be likened to a bellows or a lung: periods of exhalation, during which the country grew relatively more open to the external world and a multiplicity of internal viewpoints, have alternated with (generally longer) periods of inhalation, during which the country retreated behind its real or metaphorical Great Wall and clung fast to its essential Chinese-ness. We can see the same pattern taking place since 1949, albeit over far shorter periods of time, as pragmatism and communist ideology push and pull against one another.

When the formation of the People’s Republic was declared in 1949, no one inside or outside of China was quite sure what character the new government would assume. China’s communist revolution did have one thing to recommend it over the one that had occurred in Russia 32 years earlier: it had been a true revolution of the people, achieved with broad popular support, rather than the triumph of a small and secretive cabal, as had been the case in Russia. Yet China in 1949 had even less claim to fulfilling Marx’s conditions for communism than Russia had in 1917: ravaged as it was by decades of war, its per-capita industrial output was less than one-fourth that of pre-revolution Russia, no industrial dynamo itself. Then, too, the Russian revolution had at least been born in the cities of that mostly agrarian nation; the Chinese Communists had since 1927 made their base of power the countryside. Marx, of course, had anticipated a communist revolution of the urban proletariat, not of the rural peasantry.

There was another way in which the Chinese Communists departed dramatically from one of the core tenets of Marxism: they were strident nationalists, an orientation which was anathema to Karl Marx, who imagined an international communist movement that would do away with countries as we know them. Mao Zedong, by contrast, spoke at least as often of the need for China to regain its national dignity and learn to assert its national will as he did of utopian communist ideals. This too reflected the changed face of communism in practice. In the Soviet Union as well, the last serious belief in communism as a post-nationalist movement had been burned away by the conflagration that was the Second World War — or the “Great Patriotic War,” as the Soviets called it — in which Russians willingly fought and died in the tens of millions in the name of the motherland, not for any real or hypothetical workers of the world.

Thus we perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that Mao’s most aggressive early moves were meant to draw a clear line around the sovereign borders of the nation-state of China — the same ones that had been so indistinct for the better part of 150 years — and put an end to foreign meddling in Chinese affairs. We’ve already seen how Mao chose to join the war in Korea for this reason. But even before those events, he sent an army westward to reoccupy Tibet, which had slipped out of Chinese control in the chaos surrounding the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912. He made all of China’s borders a tangible as well as a legal truth, asserting a measure of control over the hinterlands of Outer China that hadn’t been seen in many decades.

In most other respects, however, the People’s Republic had a milder beginning than many might have expected — almost mild enough to make one think the benighted Patrick J. Hurley had been onto something when he said that the Communists were “striving for democratic principles.” If one didn’t look too hard, this new China didn’t appear that different from the multi-party state which the Americans had tried so earnestly to broker at the conclusion of the Second World War. Other political parties were initially permitted; in fact, members of them were appointed to almost half of the ministerial-level posts in the new government, although not to the most important ones. There was no thoroughgoing, long-lasting reign of terror immediately after the communist revolution in China, and certainly no equivalent to the execution of the entire Romanov royal family in Russia. (Granted, Chiang Kai-shek and and the Soong family, China’s nearest equivalents to the Romanovs, had all escaped the country before this revolution was complete.) As historian Maurice Meisner writes, “Political stability and economic development were the orders of the day. Revolutionary utopianism was not to appear on the scene until well after the new order was consolidated and seemingly institutionalized.” While land reform was carried out in the countryside, for example, it was accomplished without overmuch violence, and was not notably collectivist: individual peasants were given ownership of the land they worked, and allowed to manage it as sole proprietors. The focus of the first Chinese “Five Year Plan” — a framework for central planning borrowed, like much else at this stage, from the Soviet Union — turned out to be heavy industry rather than agriculture when it was announced in January of 1953. The plan was not a failure: the industrial output of the country more than doubled over the course of the five years.

Indeed, even the most hard-bitten Western Cold Warrior would find it hard to deny that the Communists during their first eight years in power did much that was good for China. Between 1949 and 1957, the percentage of the population that went to primary school doubled, while the percentage that went on to university quadrupled. Likewise, through the expulsion of foreign interests, the draconian punishment of smugglers, recovery programs for addicts, and appeals to the patriotism of every citizen, the Communists all but eliminated the longstanding scourge of opium abuse. Ditto the criminality that had run rampant for so many decades, most recently in league with rather than in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek’s regime. Perhaps most gratifyingly of all, the miserable position of women, for so many centuries China’s not-so-secret shame, was at long last altered for the better. In the eyes of the law, if not yet in those of most everyday Chinese, women were placed on the same level as men. Outrages like foot binding and forced marriages were formally outlawed, and wives were given permission to initiate divorce proceedings against their husbands for any reason, or for no reason whatsoever other than personal incompatibility. Then, too, the law demanded that girls be given all of the same educational opportunities as boys.

The man most responsible for carrying out these and many other practical reforms so effectively was one Zhou Enlai, a former associate of Chiang Kai-shek who had finally chosen to cast his lot with the Communists out of disgust with the corrupt government he had been serving. He had by now become the most important figure in Mao’s China aside from the chairman himself, a status he would continue to enjoy for two decades to come.

This first post-revolutionary exhalation of the Chinese body politic reached its maximum extent in the mid-1950s, shortly after the Communist Party adopted a constitution which enshrined the rights of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of the press. There followed what has become known as the “Hundred Flowers” period, so named because Mao and Zhou both endorsed the metaphor of a healthy society as a thriving garden, made up of a hundred flowers “blooming and contending.” They said that freedom of thought and speech and the robust discussions and intellectual disputes it engendered were the only ways by which China could evolve, both culturally and economically.

Writers and other intellectuals were thus not just permitted but encouraged to criticize the Party and all other aspects of the state, in the interest of forging a more perfect nation. Among them was a talented 22-year-old named Wang Meng, who penned a barbed satire of the self-righteous mediocrities who seem to worm their way into every bureaucracy, regardless of its nationality, and then stay there, as immovable and useless as the potted tree in the reception area. In the excerpt below, two frustrated would-be reformers named Wei Heming and Lin Zhen are discussing Wang Qingchuan, the piece of institutional flora that is in charge of a state-run factory.

Wei told Lin in detail all about Wang Qingchuan. Originally, Wang worked in some central ministry, but as punishment for some involvement with a woman, he was assigned to this factory as deputy factory manager in 1951. In 1953, the factory manager was assigned elsewhere, and Wang was promoted to that position. He never did anything but run around in circles, hide in his office, sign papers, and play chess.

Lin said, “Don’t keep these complaints to yourself. Criticize him, tell the higher levels about this. They cannot possibly condone this sort of factory manager.”

Wei smiled and asked Lin, “Old Lin, you’re new here, aren’t you?”

“Old Lin” reddened.

Wei explained, “Criticism doesn’t work. He generally does not join in such meetings, so where are you going to criticize him? If by chance he does join in and you express your views, he says, ‘It’s fine to put forth opinions, but you’ve got to have a firm grip on essentials and consider the time and place. Now we should not take up precious time put aside for discussing national tasks by giving vent to personal opinions.’ Fine. So, instead of taking up ‘valuable time,’ I went around to see him myself, and we have argued ourselves into the present situation.”

“And how about informing the higher levels?”

“In 1954 I wrote letters to the ministry of the textile industry and the district Party headquarters. A man named Zhang from the ministry and Old Han from your office came around once to investigate. The conclusion of the investigation was that, ‘Bureaucratism is comparatively serious, but most important is the manner of carrying out work. The tasks have been basically completed. It’s only a question of shortcomings in the manner of completing them.’ Afterward, Wang was criticized once, and they got hold of me to encourage the spirit of criticism from bottom to top, and that was the end of it. Wang was better for about a month. Then he got nephritis. After he was cured, he said he had become sick because of his hard work, and he became as he is now.”

“Tell the upper levels again!”

“Hmph. I don’t know how many times I’ve talked with Han Changxin, but Old Han doesn’t take any notice. On the contrary, he lectures me on respect for authority and strengthening unity. Maybe I shouldn’t think this, but I’m afraid we may have to wait until Wang embezzles funds or rapes a woman before the upper levels take any notice.”

On June 8, 1957, The People’s Daily — the official mouthpiece of the Communist Party — informed the citizens of China in so many words that the Hundred Flowers era was at an end. “Right-wing” intellectuals, it declared, had abused the sacred trust placed in them in order to undermine the state; the flowers had become “poisonous weeds,” which must be uprooted at all costs if Chairman Mao’s garden was to flourish. The full weight of the state came down on those who had been bold and naïve enough to criticize the powers that be. Wang Meng was packed off to a work camp for his “rightist” views and for the literary sins of “sentimentality and despondency”; he wouldn’t be released until 1978. All non-Communists in the government were dismissed to suffer public disgrace, if not worse forms of punishment, as were many card-carrying Communists who had bloomed and contended a bit too enthusiastically. For months, The People’s Daily published the cringing confessions of formerly high-placed individuals, which they offered up in a bid — sometimes successful, sometimes not — to escape the very worst. Former transport minister Zhang Bojun, for example, wrote the following, which would prove just enough to keep him alive and out of prison.

The whole nation is demanding stern punishment for me, a rightist. This is what should be done, and I am prepared to accept it. I hate my wickedness. I want to kill the old and reactionary self so that he will not return to life. I will join the whole nation in the stern struggle against the rightists, including myself. The great Chinese Communist Party once saved me; it saved me once more today. I hope to gain a new life under the leadership and teaching of the Party and Chairman Mao, and to return to the stand of loving the Party and socialism.

The parallels with the final lines of Nineteen Eighty-Four are as uncanny as they are chilling. (“He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.”) Of all the crimes committed by totalitarian collectivists, the annihilation of the individual conscience and its inseparable companion, individual dignity, is in some ways the hardest to witness, as George Orwell recognized. But such was China’s immediate future. The first post-revolutionary exhalation had ended, and the first inhalation had begun.

Why now? And was Communist China always predestined to follow this course? Such questions lead inexorably to other ones, about the character of Mao Zedong. The number of true believers in Mao as an eternally infallible, eternally benevolent leader has dwindled around the world in recent decades, as the staggering quantities of death, destruction, suffering, and sheer random cruelty which he meted out in the last two decades of his life in particular have become undeniable. Yet that still leaves us with questions worthy of debate. Was Mao always a monster who merely craved a larger stage to fully reveal who and what he was? Or did something change in him after he became China’s one and only leader — whether psychologically, what with the absolutely corrupting effects of absolute power, or even physically? (In one speech delivered in late 1957, Mao alluded vaguely to a “stroke” he had recently suffered, which he said made it difficult for him to stand.) As late as 1955, Mao could see his way clear to calling “personality cults” “a foul carry-over from the long history of mankind” with no evident irony. In the years to come, his own cult of personality would become archetypal, much to the detriment of the world and, most of all, the Chinese people.

Mao’s decision to embark on the project he named “The Great Leap Forward” — a project which would cause the worst single famine in Chinese history — is rooted in a schism between China and the Soviet Union that was becoming apparent by 1957. In truth, relations between the most populous and the largest nation in the world had never been as warm as most of the West believed and feared. Mao felt the Soviets had done far less than they could have to help his cause, both before and after 1949. He was especially incensed by the Soviets’ failure to give him the nuclear weapons he felt he needed to cement China’s new status as a nation of real geopolitical consequence. Nikita Khrushchev, who became the next leader of the Soviet Union following Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, made noises about doing so, but never turned words into action, probably out of justifiable concerns about the completeness of this one temperamental man’s hold on power in China, along with his tendency to talk about the prospect of apocalyptic war with alarming casualness and even affection. (“Out of the world’s population of 2.7 billion, one-third or one-half may be lost. If the worst came to the worst and one-half of mankind died, the other half would remain, while imperialism would be razed to the ground. In a number of years there would be 2.7 billion people again, and definitely more.”) In the throes of his fresh zeal for ideological rigidity during the post-Hundred Flowers period, Mao thought the Soviets were going soft, what with Khrushchev’s recent talk of “peaceful coexistence” with the Western world. Anyway, he had always been rankled by his subordinate role in the relationship; Mao Zedong did not gladly take a backseat to anyone. And now he had decided that he didn’t have to.

In November of 1957, Mao made a state visit to Moscow, during which he was persistently confrontational and downright insulting toward his hosts, leaving them nonplussed by his behavior. When Khrushchev made a return visit to Beijing nine months later, Mao tried deliberately to humiliate him by inviting the Russian to join him for a very public swim. “Mao was a famed swimmer,” writes Julia Lovell. “Khrushchev got by with inflatable armbands. Off Mao went, with Khrushchev struggling in his wake. Mao delighted in asking complex questions, in response to which Khrushchev could only splutter, having swallowed mouthfuls of water.”

These events were occurring just as the first Five Year Plan was coming to an end in China, with a solid record of achievement. But Mao, now well into the process of breaking entirely with the Soviets, had no desire to continue to emulate their approach to central planning, which focused on industrialization in the cities. For Mao was of peasant stock, and had led a revolution which had found its footing in the countryside. Left to his own devices, he would always look to the rural peasantry rather than the urban proletariat. He decided that the Great Leap Forward for Chinese communism would take place in the countryside, contrary though this was to the writings of Karl Marx.

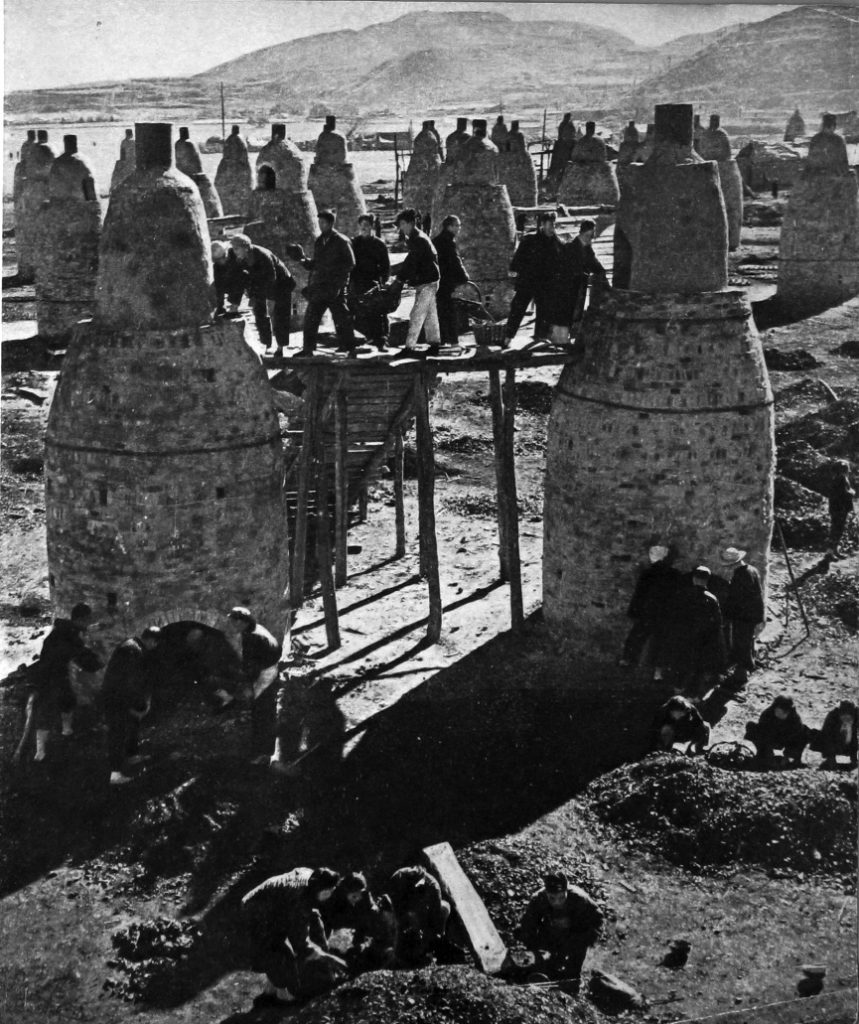

Just before the planting season of 1958 began, tens of thousands of Party officials across the width and breadth of China were given orders to collectivize all of the country’s agriculture within a matter of weeks. All private land holdings were to be given over to the collective, and all traces of individualism were to be abolished. Families were no longer allowed even to prepare their own food; the kitchens were ripped out of their houses in favor of communal mess halls. From now on, everyone would work together and eat together, everyone would think and speak alike; anyone who broke with the communal norms in even the most trivial of ways would be “criticized” by the collective, which could mean anything from a verbal haranguing to imprisonment, torture, or execution.

The Great Leap Forward achieved the exact opposite of its intended effect; it was even more ruinous to agricultural output than the similarly radical collectivism of the Taiping rebels had been 100 years earlier. All of the best practices gleaned over thousands of years of working the land were thrown out by clueless Party cadres with only ideology to guide them. Mass famine — famine on a scale never before seen even in China, a country that had known more than its fair share of it — was the inevitable result. As the harvests failed everywhere, people ate the bark off trees, ate the straw roofs off their houses, ate bird droppings and sand. Finally, they began to eat each other. First they dug up and ate the bodies in the graveyards, then they pounced on fresher sources of sustenance. A starving father told his daughter that “there’s no meat left on my body, but after I die, cut out my heart and eat it.” One couple killed and ate their fourteen year-old daughter; then, when the husband died, the wife ate him. Such horrific anecdotes illustrate that, contrary to the rhetoric spouted by so many ideologies and religions, there is no inherent nobility or redemption in human suffering; there is only the base reality of swollen bellies and glazed eyes.

The Party officials in the provinces were terrified of telling the truth to Beijing, for fear of being punished for their incompetence or, worse, suspected of harboring rightist sympathies that had prevented the communist experiment from becoming a success. So, they lied about how things were going, inflating their yields of grain by factors of two, three, or four. Insulated from the truth by the waves of fear that radiated outward from his lofty perch, Chairman Mao pondered what to do with all of the agricultural surplus that his Great Leap Forward was generating. He imagined China becoming “the granary of the world,” feeding developing nations around the globe and thereby luring them over to the communist bloc, which would now receive its marching orders from Beijing rather than Moscow. (Take that, Khrushchev!) Within ten years — twenty at the outside — China’s economy would be larger than that of the United States. It took months for the first rays of truth to break through the cloud of lies, and even then Mao persisted in believing that the reports of starvation were merely isolated, localized exceptions to a successful grand pattern, the results of a few bad apples among the Party cadres.

In the face of the unprecedented humanitarian crisis, some brave souls did dare to speak a modicum of truth to power. The most prominent early critic was Peng Dehuai, a trusted general who had been at Mao’s side since well before the Long March. In a letter he wrote to the chairman in 1959, he warned of “a growing tendency toward boasting and exaggeration on a fairly extensive scale” and of a universal failure to “pay enough attention to the specific current conditions so as to arrange our work on a positive, safe, and reliable basis. Some quotas which could be met only after several or a dozen years became targets to be fulfilled in one year or even a few months. Some techniques were popularized hastily. Some economic and scientific laws were rashly neglected.” As challenges go, Peng’s letter was pretty mild stuff; he was careful to point out that the achievements of the Great Leap Forward to date had been “really great,” and framed his suggestions as ways of fine-tuning the initiative rather than giving up on it altogether. Nevertheless, he was purged from the Party for his outspokenness and thrown into prison, where he died in 1974.

Yet the scale of the disaster only grew during the Great Leap Forward’s second year, precipitating at last the one occasion when Mao Zedong’s ongoing leadership of China was placed in serious doubt. Some imagined replacing Mao with the more moderate and sober-minded Zhou Enlai; these schemes were perhaps prevented from coming to fruition only by that man’s old-fashioned code of honor, which prevented him from plotting against the leader to whom he had pledged his lifelong allegiance, no matter how calamitous the consequences of his continued loyalty for his country. As it was, even Mao eventually saw that his current course was unsustainable. In 1960, facing real dissent at all levels of the government, combined with food shortages that had begun to penetrate even the privileged inner circles of the Party elite, he agreed to scrap the collectivization project. The surviving peasantry were allowed to return to the old ways, to try as best they could to repair their torn-up kitchens and their torn-up lives. For the Great Leap Forward had accomplished all of its goals, it was announced, by virtue of the Party saying it had; everyone could step back and relax just a bit. Alas, the devastation the Great Leap Forward had wrought could not be so easily hand-waved away: not until the early 1970s would China’s per-capita grain production return to the level it had reached just before 1958. Far more Chinese than necessary would continue to go hungry and in the worst cases to starve to death for many years to come, while the peasantry slowly repaired the damage done by the Communist Party’s bumbling and heartless intervention in matters it didn’t understand.

Historian Yang Jisheng, the author of the most exhaustively researched study of the Great Leap Forward, writes that “a figure of 36 million approaches the reality but is still too low” for the number of people who died as a direct result of it between 1958 and 1962 alone. We should take a moment to put that number in perspective in the annals of twentieth-century atrocities. It is twice as many people as died in the entire course of the First World War, about six times as many as were killed in Adolf Hitler’s Holocaust, and 36 times the number that fell victim to Joseph Stalin’s Great Purge. Like the latter two death tolls, it can justly be laid at the feet of one man.

The best defense to be offered for Mao Zedong — the best reason that we shouldn’t lump him together with those other two mass murderers — is, in the words of Maurice Meisner, that “it was not Mao’s intention to kill off a portion of the peasantry. There is a vast moral difference between unintended and unforeseen consequences of political actions, however horrible these consequences might be, and deliberate and willful genocide.” Yet the lines between these categories are rather blurred by Mao’s cavalier attitude toward the lives of people in general — the same attitude which allowed him to wave off the potential deaths of hundreds of millions or billions as the mere collateral damage of a nuclear war that might just lead to the building of a new communist world order that had him as its centerpiece. In light of this, I cannot help but feel that he would have traded the lives of 36 million of his countrymen in a heartbeat if it could have led to the increases in agricultural output that he sought.

But maybe that is overreaching. Rather than indulging in more equivalencies — false or otherwise — it should suffice to say that 36 million people died because of one man’s stubbornness, ignorance, and childish refusal to abide contradiction. When I think about the legacy of Mao Zedong, I find myself returning again and again to political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase “the banality of evil,” coined after she attended the trial of the former Nazi functionary Adolf Eichmann in 1961. The meaning of the phrase is, I think, often misunderstood. People wish to apply it very specifically to Eichmann, who was a born follower, with a bovine lack of curiosity and independent will. But Arendt actually meant it in a much broader sense. We are raised by our popular fictions to see villains as larger-than-life characters. Yet they are really defined by their smallness, by all of the qualities they lack rather than any that they possess: empathy, conscience, moral intelligence — all of the best traits of humanity, such that we often label them merely our “human” qualities. The things that they are missing lead history’s alleged “monsters” to do terrible deeds, but such characters are not really worthy of such an extravagant label. They are petty creatures, imps rather than dragons. “Evil comes from a failure to think,” wrote the Israeli author Amos Elon. “It defies thought, for as soon as it tries to examine the premises and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil.” Evil, in other words, is an absence rather than a presence.

Small wonder, then, that leaders like Mao Zedong go to such lengths to control the thoughts of their people. For at all costs they must be prevented from seeing the qualities in their leaders that simply aren’t there.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Andrew Pam

“would find it had to deny” has the opposite of the intended meaning, and looks like a typo for “hard to deny”.

Jimmy Maher

Yes. Thanks!

Derek

Mao also had the bright idea of exterminating sparrows, because they ate grain from human crops. As a result of his extermination campaign, the population of locusts and other crop-eating insects skyrocketed, exacerbating the famine. China eventually gave up and imported hundreds of thousands of sparrows from the Soviet Union.

Ecology is not to be trifled with.

Quasimojo

I could just as much objectively argue that Hitler’s control of Germany improved the living conditions of its people before the war, and you would probably be horrified that I would bend over backwards for a mass murderer to award him little brownie points. That should give you an idea of how I feel reading this article.

You say I shouldn’t lump Mao in with Stalin and Hitler. I say we absolutely need to, and your weird arguments of why Mao wanting to turn the people of China into controlled slaves without any rights makes him ‘better’ than Hitler doesn’t do anything to help your case. Mao, like any mass murderer, exemplifies the absolute worst of evil. Period.

Will Moczarski

the self-righteous mediocrities who seems to worm

-> seem

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!