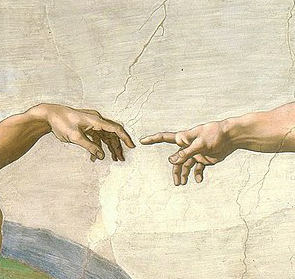

Of all the world’s great works of art, the ceiling and altar wall of the Sistine Chapel are among the most difficult to properly appreciate. This is not because they lack for immediacy or relatability; your first glimpse of the hand of God touching that of his creation Adam up there on the chapel’s ceiling can still amaze you, no matter how many times you’ve seen it reproduced and parodied out of context. No, the problem is the simple fact that so many other people are there to see the same thing that you are. For Rome is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, and the Vatican Museums, a tour of which features the Sistine Chapel as the grand finale after a gobsmacking parade of other artistic treasures, is one of the city’s two most popular attractions of all. The other one, the Colosseum, is as massive as a modern football stadium; the Sistine Chapel, by comparison, is just 6000 square feet (550 square meters) in size, smaller than many a hotel ballroom. Every day during high season, 30,000 people troop through this space, craning their heads and resisting — or not — the urge to snap a picture. (Photography is officially forbidden.) They come from all over the world, and their motivations for being there range equally widely, from devout Catholic pilgrims who have been saving up for years to visit the holy heart of their faith to slightly bored-looking package-tour travelers wishing only to check one more tourist trap off of their bucket lists. The contrasts among the members of the sweaty, shuffling crowd, not to mention between the crowd and the magnificent scenes above them, makes its own sort of commentary on the multifariousness of human existence.

But what it doesn’t make for is reflective art appreciation. Jostled by purses and elbows, wilting under the pointed gaze of the guards who make it all too clear that they’d prefer for you to move on quickly, please, so as to make room for others, even the most determined culture vultures find it hard to give themselves over to the quiet, awe-filled contemplation that the artist Michelangelo intended. As sad as it is to say, you probably will get more value out of an investment in a good Sistine Chapel picture book than a ticket to see the real thing.

This, however, is not such a book, which I possess neither the requisite high-quality photographs nor the requisite background in art history and technique to write. This book is rather predicated on the principle that all human-made wonders, no matter how majestic and other-worldly they may appear, spring from a specific place, time, and state of mind, and can thus become a window into that very specific past which formed them.

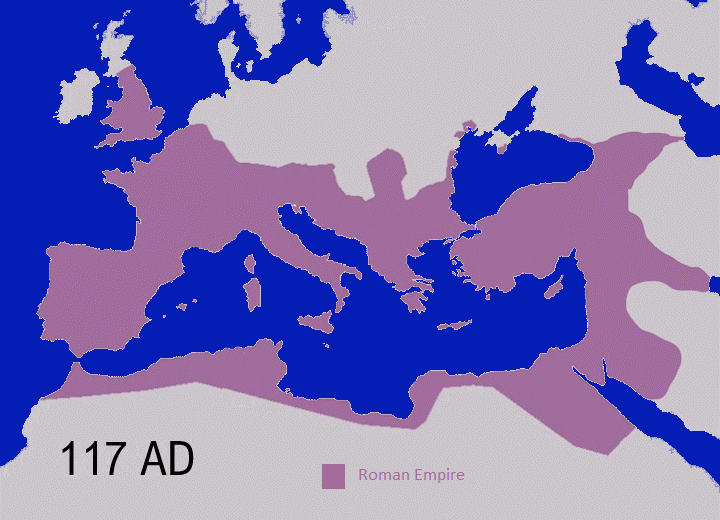

So, fair warning: this book will take a roundabout route to arrive at what 6 million visitors to the Sistine Chapel see every year, although I promise you that it will get there in the end. My not-so-secret agenda is to show you how something so beautiful, so seemingly above worldly concerns as the Sistine Chapel — literally so, in the case of the chapel’s ceiling — nevertheless comes complete with an origin story indelibly bound up with the temporal social currents and concerns of its day. To fully understand how and why the Sistine Chapel came to be, we will first have to consider how the Catholic Church came to be, and how it came to exert such a hold over the political as well as the spiritual life of Western Europe during the extended cultural retrenchment which followed the collapse of the Roman Empire. That, then, will constitute the beginning of our journey through time. During its middle stage, we’ll consider the extraordinary flowering of culture we call the Renaissance, the incubator of Michelangelo and the larger-than-life pope for whose glory he painted the chapel’s ceiling between 1508 and 1512. Finally, we will turn to the bubbling discontent in Europe about the Catholic Church and its often decadent ways that led to the Protestant Reformation, the disturbing, minor-key background music to Michelangelo’s return to the Sistine Chapel to paint its altar wall between 1536 and 1541.

Call this book the essential companion to your Sistine Chapel picture book — the story behind the stories portrayed in those timeless frescoes.

At the broadest level, the recorded history of the Western world can be divided into four epochs: the Archaic period, spanning from about 3000 BC to 500 BC; Classical Antiquity, from 500 BC to AD 500; the Middle Ages, from 500 to 1500 or so; and our own current epoch of Modernity. Catholicism is very much a creature of — in fact, in many ways the author of — the third of these. The Catholic Church’s rise corresponds with the gradual passing of Antiquity into the Middle Ages, and its troubles during the period of the Sistine Chapel’s creation correspond with the passing of the Middle Ages into Modernity.

This period of Western history tends to get not so much a bad rap as a confusing one these days. As the somewhat dismissive-sounding name “Middle Ages” would suggest, many folks persist in seeing this particular epoch as little more than a waste of 1000 perfectly good years, the long, benighted interregnum between the glory that was ancient Greece and Rome and the triumphant return of human genius in such celebrated early Modern figures as Copernicus, Shakespeare, Newton, and Bach. Our newspapers still use “Medieval” — a Latin-derived adjective meaning literally “middle-aged” — as a catchphrase for the frightfully barbaric and primitive; on the street, “getting Medieval on your ass” is what happens when the talking stops and the knives come out. At the same time, though, the Medieval lore of knights and ladies, chivalry and dragons is an evergreen staple of our novels, films, television shows, and videogames. Medieval castles and Renaissance Faires fascinate a plastic-sword-waving public, and avid players of Dungeons & Dragons learn more about the details of real Medieval weaponry than the average Medieval peasant who got run through by one of those pointy objects ever got the chance to find out. There are, it seems, aspects of the epoch that repel us, but also aspects that we find almost irresistibly alluring.

Of course, 1000 years is a long time, with room for plenty of bad and good alike. Both our skeptics and our fantasists tend to work from an incomplete picture of the real Middle Ages. The most scornful scoffers might want to reconsider their position in light of the fact that this supposed time of ignorance and stagnation gave us the vibrant patchwork of cultures and languages that still defines the Europe of today. And as for the “lazy Medieval” romantics whose most cherished idylls are filled with the likes of Frodo Baggins and Tyrion Lannister, they overlook the all-dominating role that the Christian faith played in the daily life of all levels of society. The Middle Ages were not a complete intellectual desert; they were not so much bereft of thinking as marked by a different kind of thinking, as described by the twentieth-century historian of civilization Will Durant.

To understand the Middle Ages we must forget our modern rationalism, our proud confidence in reason and science, our restless search after wealth and an earthly paradise; we must enter sympathetically into the mood of men disillusioned of these pursuits, standing at the end of a thousand years of rationalism, finding all dreams of utopia shattered by war and poverty and barbarism, seeking consolation in the hope of happiness beyond the grave, inspired and comforted by the story and figure of Christ, throwing themselves upon the mercy and goodness of God, and living in the thought of His eternal presence, His inescapable judgment, and the atoning death of His Son.

This is Roman Catholic thinking. The word “catholic” is a Latinized version of a Greek one, meaning universal and all-encompassing, an apt description if ever there was one of Christianity’s place in Medieval society.

That the universal church of Western Europe should wind up centered on Rome, from which much of the known world had been ruled for centuries before the birth of its savior, was by no means foreordained. On the contrary, “it should not be forgotten how unpredictable this outcome was,” as the historian of Christianity Diarmaid MacCulloch has written. If you had told a Christian of the first or second century that Rome would someday become the epicenter of his faith, he would surely have laughed or cursed you out of the room. The fact is that early Christians hated Rome. For proof, we need only look to the Book of Revelation, that strange, deeply unnerving final statement of the Bible, probably written around the turn of the second century. Considered in its historical context, this supposed book of prophecy is really an elaborate and lavishly violent revenge fantasy against Rome, which is personified as the grotesque “Whore of Babylon,” “the mother of harlots and abominations of the Earth,” “drunken with the blood of the saints and the blood of the martyrs.”

How, then, did Rome go from whore to home of the Holy Mother Church? To find out, we must look back to the time when that older Roman Empire was at its peak, and Christianity was just a strange cult well outside of the polytheistic pagan mainstream.

Although the legends of thousands of Christian martyrs being fed to the lions in the Colosseum year after year are probably grossly exaggerated if not outright false, the Roman emperors were definitely not always friendly toward the new monotheism in their midst. Our secular historians of today do not rule out the Catholic Church’s longstanding claim that Jesus Christ’s apostle Peter came to Rome after the crucifixion to spread the good word, only to be himself martyred there in the year 64 by Emperor Nero, who had infamously fiddled while much of Rome burned in a terrible conflagration and sought to shift the blame to the city’s nascent Christian community, an easy scapegoat to accuse of arson.

Church historians also insist that Peter was the first person in Rome to be called the Christian pope, but the secular historians are far more dubious about this point. And even if he was called pope, they are doubtful that he founded the institution of the papacy as a leadership role to be passed down from one holy man to another. Those popes whom the Church claims to have immediately followed Peter are shadowy figures of unclear historical veracity, existing only in the records of the Church itself, and then only well after the stated dates of their deaths. It isn’t until a century or so after the time of Nero that the Roman popes’ claim to being real historical figures begins to firm up.

Whenever it came to be enshrined in institution and ceremony, to ancient elites the title of pope had a downright childish ring, on which grounds they didn’t hesitate to mock it: “pope” in Latin was originally an affectionate term for “father.” (It is the linguistic root of the word “papa” which is still to be found in English and other European languages). The oddly casual honorific serves to illustrate what a small-scale affair Christianity really was in Rome in the early years, a matter of an informal father figure presiding over a tiny flock of metaphorical children.

The intellectual culture of Christianity as a whole was largely a Greek-speaking one early on. The more westerly, Latin-speaking parts of the Roman Empire were left somewhat on the outside looking in. Authors from the city of Rome were certainly not responsible for the foundational Christian texts that gradually emerged in those first couple of centuries, written versions of the oral narratives that were circulating among believers of Jesus’s actions and teachings in far-off Palestine. Then, too, the surviving reports from the early ecumenical councils which hammered out much of Christian doctrine as we still know it today make little to no mention of any Roman delegation, an indication that that city’s clerics were not especially valued participants in the most pressing theological debates of the time.

The closest thing to an intellectual heart of early Christianity was rather the Egyptian city of Alexandria, whose elites spoke and wrote almost exclusively in Greek. It was there well before the time of Jesus that the books of the Hebrew Bible had first been translated into Greek. Now, it was largely in Alexandria that the status of Jesus as a divine incarnation of God rather than a more typical sort of mortal prophet became Christian orthodoxy, not without much heated argument and even bloodshed. And then it was in Alexandria in 367 that the disparate texts that constitute the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Bible were first compiled into that one canonical holy book of the religion. (For more on how all of this came about, I refer you to the earlier volume in this Wonders of the World series on Alexandria.)

In 382, the current Roman Pope Damascus asked his personal secretary, a brilliant man of letters named Jerome, to translate the complete Alexandrian Bible from Greek into Latin. Several years later, Jerome delivered his Biblia Vulgata, meaning literally “Bible in the Common Tongue.” This Vulgate Bible would be employed by the Catholic Church for more than 1000 years, until long after Latin had ceased to be a common tongue at all, had become instead the rarefied communications medium of scholars and priests alone. Jerome was canonized for his achievement.

It might be instructive to examine the overall state of Christianity at this juncture. Far from the scattered, intermittently persecuted movement it began as, Christianity has been the religion of Rome’s emperors since Constantine’s earthshaking conversion 70 years earlier (excepting only one two-year interruption during the reign of the “apostate” pagan Emperor Julian). Christianity is by no means free of lingering internecine disputes over the nature of Jesus, but these have grown steadily more fine-grained as time has gone by. Now, the raging debate of the age is whether Jesus was and is an inseparable, eternal aspect of God — the orthodox position held by the more “civilized” parts of the empire — or the alternative known as Arianism that is popular in many of the hinterlands, which claims that there was a time when Jesus did not exist, that he was created in the course of time by God from his own essence and is thus a separate, junior deity.

Even the orthodox version of Christianity is still a rather anarchic, diffuse affair, with nothing like a single mortal leader and an associated hierarchical bureaucracy. Indeed, many Christians in 382 still consider such a thing anathema. They remember that their religion slowly rose to dominance in the Roman Empire by following the example of Saint Paul, that early “planter of churches,” who during the decades immediately after the crucifixion traveled all over the known world and preached the new faith, then left his converts to practice it as they saw fit. The freshly minted New Testament makes no explicit statement about any need for a single supreme leader for the religion beyond God and his only son.

Nevertheless, the popes in Rome did occasionally try to press a claim to authority beyond their city’s limits even in the years before 382. Some of their insistence must surely have stemmed from the arrogance that was endemic to most of the inhabitants of the city of Rome — a sense that they ought naturally to be so privileged, situated in the imperial capital as they were. But they did also cite a passage from scripture, a passage which to this day still serves as the Catholic Church’s one indelibly Biblical claim to its role in the world. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells Peter, whom he often addresses first among his twelve disciples and to whom he sometimes seems to show a special favoritism in other respects, that

Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of Hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on Earth shall be bound in Heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on Earth shall be loosed in Heaven.

There is a linguistic wrinkle that’s worth mentioning here. The Greek name of Peter, Petros, reads and sounds like a masculated version of a feminine noun meaning “rock,” petra. In the original Greek of the Book of Matthew, then, Jesus is punning on Peter’s name, a bit of wordplay that gets lost in translation.

This selfsame Peter, you’ll recall, went to Rome after the crucifixion and died there, according to Catholic historians after inaugurating the papal succession to carry forward his legacy as the anointed “rock” of Christianity. Upon these empirically unproven events and upon these two somewhat vaguely worded sentences from the Bible rests the entire claim to legitimacy of the Catholic Church, the most far-reaching, long-lasting, and influential trans-national institution in the history of the world, an institution which today has almost a billion and a half members. But that was the future in 382; almost nobody outside of Rome was buying the argument at the time. The man whom the fast-approaching Middle Ages would take as its guiding light barely did more than pass through Rome.

Saint Augustine, the most influential Christian thinker between Saint Paul and Martin Luther, was born in North Africa in 354 to a pagan father and a Christian mother. For the first few decades of his life, he hewed more to the beliefs of the former than the latter. After making a name for himself as a promising young scholar in the city of Carthage, he came to Rome to teach rhetoric at the age of 29, but soon followed other career opportunities to Milan. It was during these years that he first began to flirt with Christianity. As a scholar, he was initially drawn to a strand of the faith known as Gnosticism, long since deemed heretical by orthodox Christians for its belief in salvation through esoteric knowledge rather than faith as well as quite a number of other deviances, such as the belief by some Gnostics that the Gods of the Old and New Testaments were actually separate beings. Eventually, though, Augustine’s orderly mind became disenchanted with Gnosticism, a mystical labyrinth that seemed to lead everywhere and nowhere at the same time. He turned instead to Neoplatonism, a metaphysical elaboration on the theories of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato that shared some marked similarities with Christianity, albeit without the central figure of Jesus and his great sacrifice for the love of humanity. This suited Augustine fine: even at this time, religion remained more of an intellectual than a moral concern for him. Certainly his spiritual questing did nothing to stop him from enjoying all of the usual pleasures of the flesh of a successful young man about town.

Then, whilst strolling through a Milanese garden one day, he heard an angelic voice chanting something that sounded to him like “take it and read.” Following this advice, he pulled out the Vulgate New Testament, the only book he happened to have on him, and opened it to a random page. There he read a passage from Paul’s epistle to the Romans:

Let us walk honestly, as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying. But put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to fulfill the lusts thereof.

On Easter Sunday, 387, the 33-year-old Augustine was baptized a Christian. Soon after, he returned to the region of his birth, to be ordained a priest and then a bishop in the city of Hippo Regius (modern-day Annaba, Algeria). Here he “lived in the Country of the Mind, and labored chiefly with his pen,” as Will Durant writes.

The great minds of pre-Christian times may in many cases have believed in gods and other divine manifestations, but, whether they happened to be Stoics or Epicureans, their overwhelming concern had been this life in this world, not the rewards or punishments of any real or potential afterlife. Augustine boldly stated that the concerns of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and all of the other storied ancient wise men were frivolous, even childish.

Those who think that the supreme good and evil are to be found in this life are mistaken. It is in vain that men look for beatitude on Earth or in human nature. As the text is quoted by Saint Paul, “The Lord knows the thoughts of the wise that they are vain.” For what flow of eloquence is sufficient to set forth the miseries of human life?

Over the course of thousands and thousands of written pages, Augustine wrestled into existence a philosophy and a theology that still rings profoundly Catholic today. He emphasized as never before the fallen nature of humanity, stemming from that original sin in the Garden of Eden. Augustine was in no doubt that Eve’s tasting of the forbidden fruit was a metaphor for sexual intercourse, the unseemly means by which humans now reproduced themselves. Humans were the corrupted products of Eve’s betrayal from the time of their conception, redeemable only through the divine grace of God, who alone could forgive them their endless transgressions and cleanse them of their innumerable, ever-multiplying sins, as long as the latter were freely and honestly confessed.

Augustine’s version of Christianity was an aggressive one; he had no interest in making accommodations with those who embraced other systems of belief. The stakes were too high for that, given that he believed unquestioningly in the eternal torments of a Hell for the unconfessed and the unbelieving, a counterpart to the eternal joy of Heaven for the saved. The Bible itself fails to describe Hell as a physical space, but the notion had been creeping into Christian theology gradually over the last couple of centuries, being increasingly used as stick to be wielded against possible converts who could not be swayed by the carrot of an eternal life of peace, ease, and fellowship. “Mankind is divided into two sorts,” Augustine now wrote. “Such as live according to man, and such as live according to God. These we mystically call the ‘two cities’ or societies, the one predestined to reign eternally with God, the other condemned to eternal torment with the Devil.” He expected the governments of Christian lands to be on the side of God, expected them to support the one true faith and to punish heresy; in practice, this meant that they must take their marching orders from the religion’s leaders. Will Durant calls The City of God, Augustine’s theological magnum opus, “the first definitive formulation of the Medieval mind,” thanks to its advocacy of a muscular Christianity not afraid to use the full power of the state to achieve its ends, its fear of Satan that at times threatens to overpower even its love of God — and its tortured relationship to the sexual act, which it tends to associate so closely with the horrors of Hell.

Still, Augustine wasn’t an unremitting scold. His surprisingly readable Confessions is a far more personal, humane work than The City of God, telling of his own struggles with faith from the time of his boyhood, written not without the occasional note of wry humor. Recalling his errant youth, for example, he says that his prayer to God (or the gods) at that time was, “Give me chastity — but not yet!” One might wish that this side of Augustine was more in evidence during the Medieval epoch of history.

For all the gains their religion had made over the last century and a half or so in moving from the periphery of the empire’s life into the very halls of state, Christians in general were in some ways a disappointed bunch during Augustine’s lifetime, having seen two of their fondest hopes fail them. The first of these was tied to what would become one of the most theologically problematic passages in the entire Bible, Jesus’s statement to his followers in the Gospel of Mark that “verily I say unto you, that there be some of them that stand here, which shall not taste of death, till they have seen the kingdom of God come with power.” Taking these words at face value, the earliest Christians believed that Jesus would return to pass judgment on all people and inaugurate the end-of-days kingdom of God within decades rather than centuries of the crucifixion. This belief does much to explain why early Christianity was so lackadaisical about putting together the Bible and the other appurtenances of an organized religion; what was the point when the apocalypse was so urgently close at hand? Only when the last of those who might have met Jesus in the flesh died and the apocalypse had not come did theologians set about the gnarly task of explaining away the problematic passage and rejiggering Christianity for a longer haul, as it were.

When Constantine converted to Christianity in 325, the religion’s adherents thought they had been awarded something of a consolation prize: if not the kingdom of God precisely, they had inherited the greatest temporal kingdom that had ever existed. With a believer on the throne to lead the Roman Empire into God’s grace, their world must surely be on the cusp of a golden age the likes of which it had never known. But this too proved a false hope. Since well before the time of Edward Gibbon, historians have been debating whether Christianity was a cause of the Roman Empire’s slow unraveling in the years after Constantine or merely an innocent bystander, a witness to the inevitable ending stages of a process that had begun as early as the second century. Either way, the fall from glory instilled a fatalism about mortal existence — a palpable sense of a world in irredeemable decline — that would become another hallmark of the fast-approaching Middle Ages.

The Roman Empire split in two in 395, with one emperor in Rome, another in Constantinople. The western empire especially was all too clearly coming apart at the seams, losing control of its territory everywhere. In 402, Emperor Honorius moved his capital out of Rome, which was badly exposed to the tribes of “barbarians” who roamed the plains to its north, in favor of the more defensible seaside redoubt of Ravenna. In 410, his judgment was shown to have been correct, when a Germanic tribe known as the Visigoths almost casually wandered down and sacked the erstwhile imperial capital before moving on. (Luckily, Pope Innocent I happened to be visiting Emperor Honorius in Ravenna when they arrived. Honorius’s sister, who still resided in Rome, was not so lucky; she was carried away along with many of the city’s treasures, never to be seen again.)

Augustine died in Hippo Regius in 430 when it was under siege by the Vandals, another Germanic people that was fast overrunning the Roman dominions in his part of the world. The bitterness one senses in his later writings becomes more understandable in this light; his “City of God” was literally collapsing around him. In a final cruel twist of the knife, both the Visigoths and the Vandals were actually Christians — but Christians of the hated Arian persuasion, whose fallacies Augustine had devoted many a tract to describing in fulsome detail. Hippo Regius finally fell to the Vandals the year after Augustine’s death.

The increasing ineffectuality of the traditional secular arbiters of imperial life strengthened the role that Christianity played in civil society. Everywhere bishops and priests stepped into the breach to minister to the physical as well as spiritual needs of their flocks, in some cases even taking personal command of armies on the battlefield. Not coincidentally, this era of secular breakdown led to the only two popes who have ever been given the martial epithet “the Great.”

The first of them was Leo I, who ascended to the holy throne in 440. He was the first pope to actually succeed to any appreciable degree in exerting his authority beyond Rome itself. “The stability which ‘the Rock’ [i.e., Peter] himself received from that rock which is Christ,” Leo said, “he conveys also to his heirs.” Leo was able to exercise far more control over the rest of mainland Italy than the last dregs of the secular Roman imperial succession could manage. Indeed, he enjoyed considerable influence over what was left of the western empire as a whole. Only the eastern empire repudiated outright his claim to special authority as the heir of Peter.

The two halves of orthodox Christianity were now in the midst of a slow divergence. Having agreed to reject the Arian heresy and to accept the eternal co-equality of God the Father and Jesus the Son, they were arguing heatedly over yet another crazily fine-grained theological question: that of whether the human and divine halves of the nature of the Christ who had died on the cross were inextricably mixed, like water and wine, or were separately suspended in his prodigious soul, like water and oil. Leo took the former position, the eastern establishment the latter. In 451, an ecumenical council was convened to settle the issue in the city of Chalcedon in modern-day Turkey. Its attempt to forge a compromise by saying that Jesus could at different times be either water and wine or water and oil satisfied no one. The grumbling discord between Latin and Greek Christianity over this issue and others was destined only to grow.

Just one year after the Council of Chalcedon, Leo earned his epithet “the Great.” Rome and the rest of Italy were being threatened at the time by another army out of the north, the most fearsome yet, under the leadership of the infamous pagan warlord Attila the Hun. When all other remedies had been exhausted and Rome lay defenseless in the path of the invaders, Leo bravely rode out and met personally with Attila under a flag of truce. Exactly what was said at their meeting will never be known for sure, but Church historians later claimed that Attila saw “the apostles Peter and Paul, clad like bishops, standing by Leo, the one on the right hand, the other on the left. They held swords stretched over his head, and threatened Attila with death if he did not obey the pope’s command.” Most secular historians, by contrast, incline more to the point of view that Attila had overextended himself in penetrating this far south and had been planning to withdraw soon anyway. But regardless, the optics of the episode are clear: a Roman pope had succeeded in turning back an invading army where the secular defenders of the empire had failed. In this milieu of chaos and dissolution, the nascent Roman Catholic Church was the only institution that could still offer the people living on the Italian Peninsula even a modicum of protection. The worldly and the spiritual were becoming ever more intertwined.

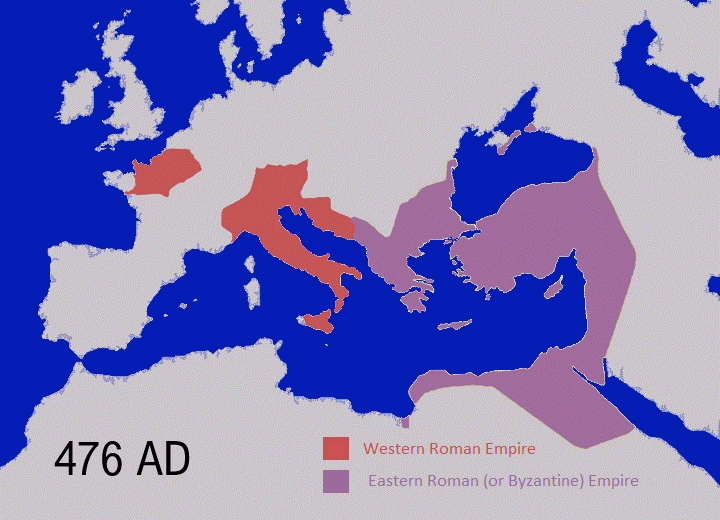

But nothing could hold off the final imperial collapse for much longer. In 476, fifteen years after Leo’s death, the western Roman Empire was finally put out of its misery, when yet another Germanic warlord forced the last emperor to abdicate from Ravenna. Now only the Church was left standing when it came to institutions with any authority at all beyond a very localized geography. Yet even it was embattled. Many of the new kingdoms that were arising to fill the power vacuum all over the Latin world adhered to Arianism.

In the early sixth century, the Roman Empire of the east, which is more commonly known today as the Byzantine Empire, actually reconquered the city of Rome and many of the other old western dominions under the slogan of “restoration.” But even this did little for the cause of Roman Catholicism, given the hostility that Greek-speaking Christians still demonstrated toward the Roman pope’s claims of supremacy and some of the other theology he preached. Emperor Justinian I of the Byzantines attempted to broker compromises between the two increasingly entrenched camps, but achieved only limited success. The Roman Church perhaps wasn’t entirely dismayed when its home city fell within ten years of the would-be permanent imperial restoration to another Germanic people, this time one known as the Ostrogoths. Although the leader of the Ostrogoths pledged his official allegiance to Arianism, he wasn’t overly interested in the sorts of theological debates that priests and bishops found so all-consuming, and was happy enough to let the Roman popes have it their way among their own people if it helped to maintain order.

If all of this is starting to become a bit confusing, rest assured that you are only vicariously reliving the spirit of the age. This really was a confusing, febrile time across the formerly Latin world, which had become a swirling maelstrom of clashing groups and cultures, where the dictum of might makes right was the only one still in force. Until fairly recently, historians typically referred to this period as “the Dark Ages.” Most have now rejected that term as too prejudicial by half, but there is at least one sense in which it undeniably applies: literacy rates and with them literary culture declined precipitously, meaning that history quite literally goes dark for us during this era. We possess almost no secular texts at all dating from the years between 550 and 800. But the loss to history extends even beyond that window of time. Because paper and ink could be expected to hold up only for a few centuries, those documents from the past which were not semi-regularly copied and recopied were doomed to be lost. The holes this period has left in our bibliography of Antiquity as well frustrate and infuriate scholars to this day.

The one exception to this retreat from the life of letters and the mind was the Church, whose priests and monks continued to read and write the old language of Latin, even as it passed out of the vernacular forever. In one of those supremely ironic twists that history sometimes likes to give us, a religion that had been born among the illiterate poor of Palestine and been mocked for centuries as suitable only for “foolish and low individuals and slaves,” as one irate Alexandrian intellectual put it in 175, was now the last remaining beacon of learning west of Greece.

Which isn’t to say that the Christian life of the mind was a particularly optimistic one. In such an environment as this, the thoughts of many Christians, lettered and unlettered alike, turned again to the apocalypse and the second coming; the Book of Revelation did, after all, prophesy a period of just such unprecedented chaos as this as the prelude to Jesus’s return. One of these believers in an imminent apocalypse was the second and last pope to be called “the Great,” an even more important figure than Leo.

Gregory was born in Rome in 540, the scion of a prominent and wealthy family. Like Saint Augustine, whose writings would later have a huge impact on him, he was focused on worldly things as a young man; he rose to become the prefect, or mayor, of Rome by the time he was 33 years old. But soon after, he had a spiritual awakening. Convinced that the second coming of Christ was just around the corner, he resigned his post and used his family fortune to found seven monasteries around Italy, then gave the rest of it away to the poor of Rome. He himself went to live in one of the monasteries, subsisting on raw vegetables and fruits when he deigned to eat at all, shattering his health forever through his extreme asceticism. Even when he went to Constantinople to serve as a sort of diplomatic liaison between the two halves of orthodox Christianity — a thankless task if ever there was one! — he continued to live like a monk in the heart of one of the wealthiest cities in the world. Church tradition credits him with the invention of Gregorian chant as a way of coming closer to God, although most secular historians now believe that that meditative, indelibly Medieval form of music stems from a somewhat later date. Either way, the fact that he is believed to be responsible for such a pillar of Catholic worship says much about the reverence with which he has been regarded within the Church for a millennium and a half.

In 590, his example of absolute devotion to God caused him to be consecrated pope, because the city of Rome was in the midst of a terrible plague that seemed well-nigh apocalyptic in itself, and it needed all the help from on high that it could get. Legend says that his first act in his new office was to lead a penitential procession through the streets. When they set off, the people saw a vision of the archangel Michael hovering above them, menacing them with a flaming sword. But when they reached the procession’s end, they saw the angel sheath his sword. Gregory’s faith had led them back to God’s grace and mercy; the plague among them dissipated. It set the pattern for the rest of his tenure, that of a profoundly spiritual man who had an uncanny knack for getting practical things done.

Did you enjoy this chapter? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Ilmari Jauhiainen

Intriguing topic for the new series and a good start! I was just a bit perplexed by one sentence:

“It was in Alexandria that the doctrine of salvation through faith alone rather than knowledge or works was enshrined”

I have a really hard time figuring out what movements in Alexandria you are referring to here. Usually the phrase “salvation through faith alone” is associated with Martin Luther’s fight against indulgences. The closest equivalent in late antiquity I can think of is the Pelagian controversy around the first decades of 5th century, which centred on the very question whether humans could gain salvation through their own choice and deeds or whether they were so tainted by the original sin that they needed the divine grace for this. The problem is that the Pelagian controversy was clearly a battle within Latin Christendom, with Augustine and Jerome being the ones leading the fight against Pelagius (also a person from the Western side of the empire).

Jimmy Maher

Yes, I was conflating some things there. I’ve removed the offending sentence. Thanks so much!

Andrew McCarthy

Excellent article! As I recall, the surviving letters of Pliny the Elder include letters from his time as governor of a Roman province, in which capacity he was required to execute unrepentant Christians at a time when the religion was illegal in the Roman Empire. I vaguely remember reading that he would interview suspected Christians and ask them three times (I think) to deny their membership of the religion and/or agree to the divinity of the emperors. For his part, Pliny would’ve vastly preferred it if they just committed a bit of minor perjury to save their lives, but many Christians (perhaps not wanting to follow the bad example of Peter in the New Testament) preferred to profess their religion openly and thus achieve martyrdom – a death sentence which Pliny figured they had had ample opportunity to evade if they wished.

Jimmy Maher

There was indeed a huge cult of martyrdom in early Christianity. The writings of the early church fathers are filled with lovingly detailed descriptions of bloody deaths. It can almost read like a sort of mass masochism today.

Martin

I think in the text of the St Augustus picture you are missing the word “few” in the first sentence.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Joe Vincent

Superb start to yet another epic walk through an epoch!

Minor edit – ‘Many of the new kingdoms that were arising to fill the power vacuum all over the Latin world adhered to Arianiam.’ I suppose the last word in that sentence should be ‘Arianism’.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Eriorg

Even the orthodox version of Christianity is still a rather anarchic, defuse affair

Do you mean “diffuse”?

Paul’s epistles, which make up 21 of the 27 books of the freshly minted New Testament

(According to Wikipedia:) 21 is the number of all the epistles, including the ones not by Paul. There are only 13 Pauline epistles.

Jimmy Maher

Ouch. I was confusing the contemporary debate about the Pauline epistles, which many scholars no longer believe to be all the work of a single person, with the epistles as a whole. Thanks!

Michael Russo

Great start to the new book (I feel like a reader of Dickens back in the day, reading my books in a serial fashion). I feel like a bit of a cliffhanger ending with Gregory there, I just wanted to keep going! Can’t wait for the next installment.

Jimmy Maher

I’m a huge lover of Victorian literature (although not such a huge fan of Dickens), so this comparison is dear to me. 😉

Peter Olausson

Excellent beginning of a worthy subject. Eagerly looking forward!

One thought, is it general knowledge that the name of Peter means “rock”?

Jimmy Maher

Good point. I added a couple of sentences of explanation. Thanks!

David Boddie

“…those documents from the past which were not semi-regularly copied and recopied was doomed to be lost”

was -> were

It’s interesting to think of the Catholic church as a surviving institution of the Roman Empire, particularly during the years following its collapse, preserving the language and some of its traditions. It’s not something I’d reflected on very much.

BL

You appear to have completely overlooked the fact that early Christianity was essentially an offshoot of Judaism. Christianity may have been a new monotheism in the midst, but given that the Romans ruled Judea well before the emergence of Christianity, the concept of monotheism wasn’t new to them at all.

Jimmy Maher

Not overlooked, just already written about. 😉 As noted in this chapter proper, I covered the origins of Christianity, including the fact that Jesus saw himself and was seen by others during his lifetime as a *Jewish* prophet, in the latter stages of my Alexandria series, starting here: https://analog-antiquarian.net/2021/07/09/chapter-15-the-prophet-from-galilee/.

Will Moczarski

An excellent start to another intriguing book, Jimmy!

Some nitpicks:

Honorious’s sister

-> Honorius‘s sister

partcipant

-> participant

was doomed to be lost

-> were

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!