July 22 – October 21, 1520

The man of twists and turns Ferdinand Magellan can confound us modern souls just as thoroughly as he could his contemporaries. We see many qualities in him that we instinctively admire: qualities of ambition, of determination, of boundless ingenuity. Perhaps most impressively of all, we see in him a conviction that was by no means universal among his aristocratic peers: that loyalty should run both ways in the chain of command. This was the conviction that caused Magellan to never, ever leave his men in the lurch, to always return for them in their hour of need.

And yet, his many fine qualities notwithstanding, Magellan remains a man of his time rather than our own. When we are forced to confront this reality, it can bring us up short. Certainly his treatment of Antonio Salomone and Gasper de Quesada, not to mention his mutilation of the corpse of Luis de Mendoza, tell us that his notions of justice were somewhat different from our own. And now I must tell you of his reprehensible behavior toward the Tehuelche people, who fed and clothed his men and taught them how to survive in the dark, frigid southern climes in which they found themselves stranded during the middle months of 1520. Magellan elected to repay all these kindnesses by kidnapping a pair of Tehuelche, in order to take them onward into the unknown with his expedition and eventually back to Europe, where they could expect to end their days on exhibit like animals in a zoo.

The whole sorry episode does have some mitigating factors, which, in fairness to Magellan, I should mention here. It had been customary ever since the Portuguese had first begun to sail down the coast of Africa for European explorers to bring back native slaves. In addition to their practical utility, these became an odd sort of status symbol, another form of exotica to be paraded around by their owners. Sometimes master and slave developed a real bond; as we’ve seen, Magellan had a long-serving slave of his own, the faithful Enrique, who had left Malacca as his side, then stayed there through his further adventures in Morocco and all of his efforts to get his westward expedition funded by first the Portuguese and then the Spanish king, and was still there with him in Puerto San Julián now that it was well underway. Still, for all that a man like Magellan might express affection toward a man like Enrique, it was always the affection that one might show to a particularly brave and clever dog rather than a friendship between equals. The root cause was a failure of imagination: Europeans just couldn’t make the mental leap to seeing people whose skin was a different color and who had grown up with different languages and different gods as fully realized human beings like they were. They held their charges’ “primitiveness” in technological terms — which was in truth more a result of certain accidents of environment and history than any sign of innate inferiority — against them as proof that there was a clear hierarchy among the races of humanity, just as there was a hierarchy of blood within the ranks of the white race. Magellan was as sure of all of this as anyone else of his time and station.

Then, too, it was actually written into Magellan’s contract with the Spanish crown that he was to try to bring back “samples” of any new native peoples he should encounter for the amusement and edification of the Spanish court. The Tehuelche were indeed a previously unknown native people, and Magellan was nothing if not a stickler for the letter of his duty. He was hardly unaware that these tall, muscular men made for unusually spectacular specimens.

So, even as the sailors’ new native friends were helping them in so many ways, the captain general was watching and waiting for an opportunity to abduct a couple of their number. One day in late July, he saw his opportunity and promptly seized it.

The Tehuelche were every bit as curious about their strange, possibly divine visitors from across the waters as the visitors were about them. On this day, four strapping young natives indicated to Magellan with grunts and gestures that they would very much like to be taken aboard one of the ships, just to see what was what there. Spotting his chance, Magellan hastily agreed, commandeering a launch to row over to his freshly re-caulked and refurbished flagship.

The guests had no way of knowing that their host was plotting a dirty trick every bit as guileful as Odysseus’s Trojan horse. After the four Tehuelche had spent some time oohing and aahing over the intricacies of canvas, cables, and capstan, Magellan separated two of them from their companions. He began to load these two down with gifts: knives, forks, mirrors, bells, glasses. When their hands were completely full, he showed them a pair of iron rings, which seemed to them as wondrous as anything else. The pair wanted to call to their companions to help them bear this latest booty away, but Magellan signaled that there was no need. He showed them how he could fasten the rings around their ankles; that way they could bring them home without needing to juggle them in their hands. They readily acceded to the wisdom of this, whereupon Magellan and an associate snapped the rings into place. Then, before the unfortunate pair of Tehuelche knew what was happening, they fastened into place as well the chains that turned the iron rings into fetters.

Chaos ensued. The captured pair bellowed for help as soon they realized that they had been tricked. Their companions tried to come to their rescue, throwing off the sailors who tried to stop them like dogs shaking off water. It took virtually the entirety of the skeleton crew that was aboard the Trinidad to subdue the two would-be rescuers and force handcuffs over their wrists.

This left Magellan stuck with four prisoners, when he really only wanted two. While he was considering what was to be done with the superfluous pair, one of the first two kept up a continuous, plaintive wailing. A perturbed captain general sent for Antonio Pigafetta, who was the best at communicating with the Tehuelche. The little Italian was at first shocked to find out what had transpired aboard the flagship, but he soon recovered his wits and figured out that the man was upset at the prospect of being taken away from his wife forever. This was a surprise to everyone; in a poignant illustration of just how difficult it was for the sailors to see the natives as fully human just like them, no one had spared a thought about what it must mean for these men to be taken away from everything and everyone they had ever known without even being offered a chance to say goodbye.

That said, Magellan now showed that, thoroughgoing product of his time and culture though he may have been, he was not a man without a heart. He decided to allow the man’s wife to join him. This was a rather extraordinary concession on the face of it, a blatant violation of his usual policy of allowing no women to travel with the fleet. (On the other hand, to bring a man and a woman — a native breeding pair — back to Europe might be a coup of its own…)

Magellan decided to send a party of sailors out on a delicate mission indeed: to deliver the two unwanted native men back to their people and to find and fetch the one captive’s wife. It wasn’t entirely clear how all of this was to be accomplished, but the captain general did put a great deal of store by the fact that his sailors had muskets and the Tehuelche did not. To lead the party, he chose João Lopes Carvalho, the Portuguese pilot of the Concepción, who had lived with the Tupi people of Rio de Janeiro for four years, taking a native wife of his own during that time. Carvalho, Magellan thought, might have a special way with the Tehuelche because of this experience. Pigafetta was sent along as well, thanks to his own special ability to communicate with the Tehuelche. Nine burly men-at-arms rounded out the two prisoners’ escort.

History does not record whether Carvalho saw the irony in being sent to fetch the wife of another man now, after Magellan had so recently forced him to leave his own behind in Brazil. Be that as it may, he was perhaps not the right choice to lead the excursion, for it quickly devolved into a farcical comedy of errors. The little group had barely begun the trek of several miles to the place where the peripatetic Tehuelche had their current camp when one of the prisoners managed to slip out of his handcuffs and make a dash for freedom. The sailors had no chance of running down this great gazelle of a man who had spent his life bounding over these steppes, even as they weren’t cruel enough to shoot him down; instead they cursed fruitlessly and watched him disappear over the horizon. Where he ran to, as it happened, was exactly the same place they were intending to go: back to his people’s camp. He found that the men of his tribe had all gone out hunting, leaving only the women behind. So, having warned the women — including the sought-after wife — to get out of Dodge before his former captors arrived, he set off again on the trail of the men.

Meanwhile, back with the escort party, the other prisoner made his own frantic dash for freedom, albeit with his hands still bound. With this advantage working in their favor, the sailors were able to catch him and force him to ground. When he continued to struggle, one of them smacked him unconscious with a handy rock. They hoisted the big man onto their shoulders and straggled on as best they could, finally reaching the now-abandoned Tehuelche camp just as the short winter day was shading off into a long winter night. There was nothing for it but to wait here for the sun to return.

The night that followed was part horror, part slapstick burlesque. The escapee had by now located the hunters, and the Tehuelche men, who were understandably incensed by their visitors’ betrayal after all they had done for them, crept up to the edges of their former camp to unleash volleys of arrows. Each time the barbed shafts came whistling out of the darkness, the panicky sailors responded by firing their muskets wildly in whatever direction they seemed to be coming from, which in turn sent the Tehuelche scrambling to get away from these infernal weapons of the gods from across the sea who had turned out to be demons. And so it continued all night long. One arrow struck one unlucky sailor in the thigh, severing an artery. He bled out within minutes.

The rest were still alive when the morning light at long last ended the deadly game. Cold, scared, and petulant, the sailors burned all of the dwellings in the camp as a way of venting their anger, then set off for home, leaving the last prisoner still tied up where they had thrown him down the previous day. “Certainly these giants run faster than a horse, and they are very jealous of their wives,” wrote Pigafetta in his journal, seeming for all the world utterly nonplussed by the Tehuelche’s perfectly natural reaction to the violent abduction of some of their number. Once they reached their destination, there was nothing for it but to tell Magellan how badly they had botched their assignment; history does not record how that uncomfortable interview proceeded. Which isn’t to say that the captain general was without blame. Far from it; the whole business had been a bad, ill-conceived one from the start, and that was all down to him.

Any way you look at it, the episode was as brutish as it was pointless, as cruel as it was stupid, one of the absolute lowlights of the entire expedition. It almost defies belief that the Magellan who instigated this string of unforced errors was the same man who, just a few months earlier, had put down a mutiny and cemented his control over his fleet so masterfully. Everyone, it seems, can have an off day.

Magellan’s off day had major, far-reaching consequences for his expedition. At a stroke, he had transformed a convivial, mutually supportive relationship with the Tehuelche into one of implacable mutual hostility. The little village and ship works which the sailors had constructed on the shore of the bay must now be guarded as vigilantly as any beachhead in war. Even so, volleys of arrows flew into its midst from time to time without warning. The fidgety bunker mentality they produced couldn’t be displaced even by the days that were slowly getting longer once again, the first clear sign that this endless winter would in fact come to an end someday. Through it all, the two sullen kidnapped Tehuelche — the reason for all of the stress and pain — were held separately, one aboard the Trinidad and the other aboard the San Antonio, in order to keep one prisoner from freeing the other if he should somehow escape. Needless to say, there was no more talk of spousal reunions. The final punchline to the sorry farce is that neither captive would survive the long voyage that still lay before the fleet for any royal court to ogle. Magellan poisoned his relationship with the Tehuelche for literally nothing.

In this atmosphere of palpable anger and menace, everyone just wanted to get out of Puerto San Julián as quickly as possible. The sailors worked like the demons the Tehuelche now believed them to be to complete the re-caulking and refurbishing of the Concepción, the last of the ships in line to receive this treatment. Even once this labor was completed, however, they were still trapped in the little bay that had now become such a den of danger. For, longer days or no, winter had yet to release its grip on this part of the world.

Magellan thus had plenty of worries already when word reached him that Juan de Cartagena, who had been held prisoner in a lean-to at the edge of the encampment for the past three months, was, incredibly, back to his old ways. Cartagena was very chummy with one of the two priests attached to the expedition, a Frenchman from an aristocratic family by the name of Bernard Calmette. Despite his own intense religiosity, Magellan had never trusted Calmette for this reason, had always made his Confessions to the other priest, a common named Pedro de Valderrama whom he would normally have considered to be beneath him. Now, it seemed, Cartagena was using Calmette as a messenger, trying to persuade the sailors to break him out of his improvised prison cell and help him to finish the job of mutiny. It had all become a bit pathetic by this point; whatever credibility Cartagena had still possessed among the sailors after suffering pillorying and other humiliations at the hands of Magellan had been annihilated forever by his cowardly performance in those first days of May. But my God, Magellan wondered, when would this entitled gadfly cease trying to bite him?

The answer to that question being self-evidently never, Magellan took the drastic measures he had avoided for so long. On August 11, 1520, he sent Gómez de Espinosa to round up both the source and the propagator of the most recent stirrings toward dissent. Cartagena and Calmette were ushered quietly into a longboat packed with supplies and several armed guards. While the prisoners looked on in mounting consternation, the boat was rowed to an islet near the mouth of the bay. As Espinosa’s men began unloading the supplies, the truth of what was being done to them fully dawned on the passengers, and the crying and pleading began. Unmoved by this soft-living pair of hangers-on who offended his every notion of manly honor, Espinosa paid them no heed whatsoever, just kept on with his work. The guards had to physically beat the castaways back as they pushed off in the longboat again, leaving the aristocrat and his pet priest behind with only enough food for a few months and the makings of some basic shelter. These were the last concessions they would ever receive from Magellan.

It was for all practical purposes a death sentence, and an unusually cruel one at that. For this pair were no Robinson Crusoe and Friday; no two men in the entire fleet could have been less equipped in mind and body to make a go of it alone in a hostile wilderness. Magellan was finally prepared to accept the consequences back in Spain of taking this ultimate step, just to have Cartagena out of his hair once and for all. Ditto the consequences with God of condemning one of his ordained priests to such a miserable fate.

The ships were now all buttoned up tight, ready and anxious to depart this bay of festering discontent at almost a moment’s notice. Each day, Magellan sent boats out to check on the weather. On August 23, one of these returned with the report that he had been waiting for: the near-constant gales out to sea were easing. Without another thought, Magellan ordered the fleet to weigh anchor.

As they passed out of the bay, the ships sailed close by the islet where Cartagena and Calmette had been stranded. The two pathetic little figures could be clearly seen and heard there at the edge of the water, waving and shouting frantically, begging one last time for mercy. But Magellan had no mercy left to give. Cartagena and Calmette would never be seen by European eyes again. They presumably perished of starvation, or exposure, or under a hail of Tehuelche arrows — perhaps the kindest possible death, all things considered.

In addition to this forlorn pair, the expedition left behind in Puerto San Julián a large cross at the top of the tallest hill, proclaiming this remote part of the world to be, like most of the rest of the Americas, the property of the king of Spain, by the august decree of His Holiness, the pope in Rome. To Europe, meanwhile, Puerto San Julián would bequeath, via the enthusiastic if factually imperfect medium of Antonio Pigafetta, tales of extraordinary “giants,” noble savages with mystical powers. A century later, William Shakespeare would read Pigafetta’s journal, and would weave it into The Tempest, his play about magic and intrigue on a distant island. The bard directly borrowed the name of the Tehuelche people’s supreme god, as transcribed by Pigafetta: Setebos. “I must obey [him],” says the native slave Caliban of his white master Prospero. “His art is of such power, it would control my dam’s [mother’s] god, Setebos, and make a vassal of him.” Small wonder that so many have called The Tempest an allegory of the colonial experience, arguably the first ever written.

In the here and now of 1520, Magellan soon had cause to regret his hasty departure from Puerto San Julián. For it quickly became obvious that the reprieve in the weather had been no more than that. Already by nightfall on August 23, the wind was bellowing through the ships’ masts once again, bringing with it yet more snow, ice, and sleet. Under these awful conditions, the vessels struggled to stay in contact and to make any progress at all down the coast. All the while, they were forced to dodge — and sometimes fail to dodge — great floating chunks of ice. Clearly they had jumped the gun; this was untenable. Even if they stayed afloat for the time being, the ships’ hulls would be battered horribly if they stayed at sea for very long, undoing all of the sailors’ hard work of the last few months.

Magellan decided to make for the Santa Cruz estuary. It might seem to superstitious sailors a place of ill omen, what with the fate the Santiago had suffered there, but it was also known to boast islets full of seals to supplement the fleet’s foodstuffs and let Magellan keep his hardtack in reserve that much longer. Just two days after leaving Puerto San Julián, the ships sailed around those treacherous shoals that had proved the undoing of the last command of Juan Rodríguez Serrano, who was now in charge of the Victoria. The storm wasn’t quite as violent this time; all of the ships made it safely inside.

There the sailors built themselves another encampment on the shore, and settled down to the work of hunting, butchering, and smoking seals, then loading the meat into the ships’ holds. Once their vessels had been stuffed to the gills with this provender, there was little left for the men to do but see to their day-to-day needs and wait for winter to loosen its icy grip more than momentarily. The nights especially were still bitterly cold, but they now had warm clothing made from guanaco fur and seal blubber. All in all, they enjoyed this break almost as much as they had the one in Rio de Janerio, knowing as they did that every precious day of it was one more day’s respite from the toil, terror, and privation that were doubtless still to come.

For his part, Magellan, who wanted desperately to resume the search for his westward-leading strait, seethed with impatience from first to last. And yet in the months to come he would have good reason to thank his God for the storms that trapped him here, for it is questionable whether he and his men could have survived what was still to come without the seal meat that they were able to hoard away in their ships’ holds during this layover.

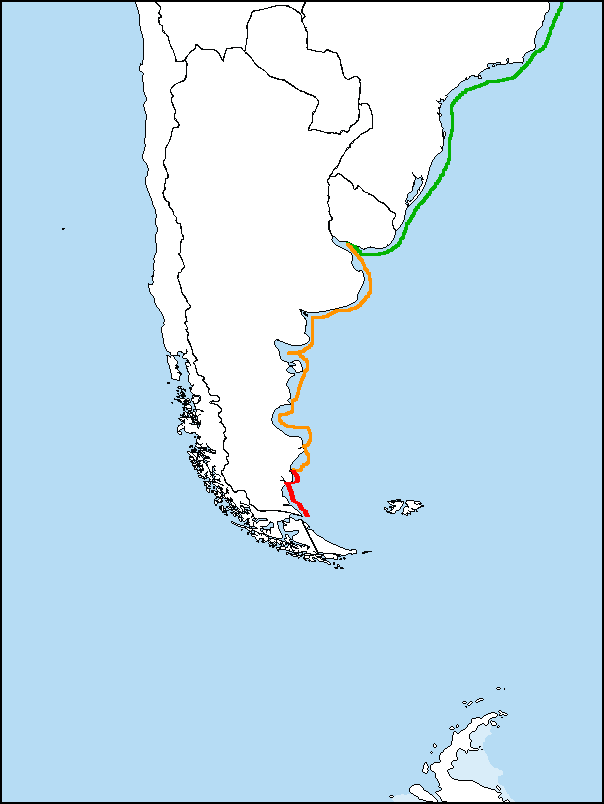

Slowly, a real seasonal change began to make itself felt. As well as continuing to grow longer, the days became milder and dryer, comparatively speaking. On October 18, 1520, the fleet departed the Santa Cruz estuary to resume its slow, probing progress down the eastern coast of South America. Thirteen months had now passed since the departure from Spain, of which the last five and a half had been spent immobilized here in Patagonia. With the Mar Dulce having proved a dead end and one of the five ships now lost, the prospects for eventual success looked in some ways worse than they had before the expedition had set out.

At the same time, though, Magellan felt he had some grounds for cautious optimism. He had eliminated, so he believed, the dissension which had been undermining his position and his authority for so long. All four of the ships under his command were now truly under his command, being captained by himself and his unquestioned loyalists. And not only had he escaped the worst consequences of his poor decisions at Puerto San Julián, but he was leaving its climes now with warm clothing on his sailors’ backs and holds full of food. In this sense, the fleet was actually better prepared for whatever might lie ahead than it had been when it left Spain.

Then, just three days out of the Santa Cruz estuary, Magellan’s prayers were answered, his faith justified. He found the westward-leading strait he had been seeking.

Did you enjoy this chapter? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it and to gain free access to the ebook versions of all completed series. You can pledge any amount you like.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)