On July 1, 1798, one of the strangest invasion fleets in history began disembarking troops on the Egyptian coast five miles (8 kilometers) west of Alexandria. The 335 ships carried all of the usual accoutrements of war, including 171 artillery pieces, 1200 horses, and 40,000 soldiers. But they also held 167 men of science, along with an array of cutting-edge scientific equipment, several printing presses, a library of over 500 books, and even a complete hot-air balloon. For the leader of the invasion was the French general Napoleon Bonaparte, who consciously styled himself after Alexander the Great, that enlightened conqueror who had, according to the traditional telling at least, brought the gifts of Progress and Civilization to the benighted peoples he subjugated. Napoleon couldn’t resist the symbolism of starting his own eastern empire in the very city of Alexander. “The first town we are going to encounter was built by Alexander,” he told his soldiers before the landings began. “We shall find, at each step we take, souvenirs of deeds to inspire emulation by the French.”

Among the invasion fleet’s many non-martial hangers-on was a diplomat, writer, and artist named Vivant Denon. He stared across the water at Alexandria with all the eager melancholy of a hopelessly romantic soul.

When the shadows of the evening delineated the outline of the city; when I could distinguish on our approach the two ports; the thick walls, flanked by a great number of towers, which at present contain nothing but hillocks of sand and a few gardens, in which the pale green hue of the palm trees fiercely tempers the burning whiteness of the soil; the Turkish fortress, the mosques, their minarets or towers, and the celebrated Pillar of Pompey, my imagination recurred to past ages. I saw art triumph over nature, and the genius of Alexander employ the active medium of commerce to lay on a barren soil the foundation of a superb city, which he selected to be the depository of the trophies of the conquest of the universe. I saw the Ptolemies invite thither the arts and sciences, and form the library, to destroy which the hand of barbarism was several years employed. It is there, said I to myself, reflecting on Cleopatra, Caesar, and Antony, that the empire of glory yielded to the empire of voluptuousness. I next figured to myself stern ignorance fixing its seat on the masterpieces of the arts, completing their destruction, but unable, notwithstanding, to disfigure utterly the fine characteristics by which they are stamped, and which belong to the grand principles of their original plans.

But Denon was forced to reckon with a rather less rapturous reality when, having chased away the surprised and undermanned garrison of the fort that guarded the harbor, the French marched into Alexandria proper. The city was the merest shadow of a shadow of what it once had been. Its status as a major port — its most enduring claim to continued importance during and after antiquity — had disappeared by now, as had any obvious trace of the towering lighthouse that had once guided ships into its harbor. The canal which linked the city to the Nile Delta had been allowed to silt up to such an extent that barges couldn’t even get through anymore. Alexandria was reduced to little more than a fishing village, poor even by the standards of the rest of Egypt, scratching out a living amidst the ruins of its former glory. Egypt’s important ports, such as they were, were now to be found elsewhere, at Rosetta and Damietta.

Only a few structures from ancient times still stood erect and reasonably intact. The most noticeable among them were the granite column which the French erroneously referred to as Pompey’s Pillar and one of the three obelisks that would mistakenly become known as Cleopatra’s Needles; its two sisters were to be found lying toppled but whole nearby. Denon’s tone changed once he got a closer look at the city: he now described Alexandria’s architecture of ruin with all the withering contempt of an offended European aesthete.

The edifices bring unceasingly to the remembrance destruction and ravage. The jambs and lintels of the doors of the dwelling houses and fortresses consist entirely of columns of granite, which the workmen have not taken the pains to shape to the use to which they have applied them. They appear to have been left there merely with a view to attest [to] the grandeur and magnificence of the buildings, the ruins of which they are. In other places a great number of columns have been applied to the construction of the walls, to support and level them; and these columns, having resisted the ravages of time, now resemble batteries. In short, these Arabian and Turkish buildings, the productions of the necessities of war, display a confusion of epochs, and of various industries, more striking and more approximated examples of which are nowhere else to be found. The Turks, more especially, adding absurdity to profanation, have not only blended with the granite bricks and calcareous stones, but even logs and planks; and from these different elements, which have so little analogy to each other, and are so strangely united, have presented a monstrous assemblage of the splendor of human industry and its degradation.

Rummaging through this palimpsest of Alexandria’s fabled past and shabby present, Denon and the rest of the French invaders were left asking just how the city could have been brought so low over the course of the millennium and change since it had passed out of Western histories. They would soon be asking much the same question about all of Egypt. The Arabic printing press which they brought with them to publish Napoleon’s propaganda was the first one ever seen in the country, 350 years after the Gutenberg revolution. Suffice to say that their would-be civilizer-in-chief had his work cut out for him to undo the many centuries of Egyptian and Alexandrian decline.

But then, Napoleon himself was perhaps less unique than he liked to believe, being just the latest of a long line of foreigners to lay claim to Egypt over the course of millennia. As we’ve seen, even those Arab Muslims who seized control of Egypt during the mid-seventh century were far from the first group of outsiders to do so. By the time they arrived, an ethnic Egyptian hadn’t ruled the country since Nakhthorhes, the last native pharaoh, had been deposed almost exactly one millennium earlier. Since that event, Persians and Macedonians and Romans and Byzantines had come and gone and sometimes come again, whilst the indigenous culture of the people they ruled lived on independently of its foreign overlords. There was little initial reason to assume that it would be otherwise with these latest conquerors from Arabia, speaking yet another strange language and holding themselves apart from the populace, just like all of their predecessors.

This time, however, it did turn out differently. Over the six centuries after the Arab conquest, the common people of Egypt slowly transformed themselves into an only modestly distorted mirror image of their rulers. It’s difficult to say with complete certainty why Egyptian and Arab culture proved to be water and wine instead of water and oil. Ethnic prejudices, or rather the lack thereof, may have been a key differentiator: unlike those foreigners who had ruled Egypt before, the Arabs were prepared to accept their Egyptian subjects as equals if they but learned Arabic and converted to Islam. This created an enormous enticement for ambitious native Egyptians to do both things.

As this process of cultural blending was going on in Egypt, the universal Muslim brotherhood espoused by Muhammad was breaking down into rival factions, as all such movements have invariably done in the course of human history. Egypt was both a principal battleground and an important prize for the feuding caliphates, changing hands several times. Then, at the end of the eleventh century, Crusaders began to arrive in Egypt from Europe. Although the Crusaders themselves considered Egypt’s Muslims and its monophysite Christians to be almost equally heretical, this period became a tragic turning point for the latter; Egypt’s Muslim rulers now came to regard all Christians with hatred, including their own homegrown breed of same. To escape their censure, countless more Egyptian Christians converted, while those who stayed steadfast in their faith suffered concerted persecution for the first time. Beginning in 1353, a vicious series of official pogroms devastated Egypt’s Christians: mobs surrounded Christian churches all over the land, and forced their congregations to choose between pledging their troth to the God of Islam or being burned alive inside their infidel houses of worship.

By the fifteenth century, the vast majority of Egypt’s population had abandoned Christianity in favor of Islam. Meanwhile Coptic Egyptian had become a “dead” language much like Latin is today, used only in the liturgy of the beleaguered Coptic Church, even as rulers and subjects elsewhere in Egypt had interbred to such a degree that there no longer existed any real distinction between Egyptian and Arab in society at large. The active persecution of the Coptic Christians would continue for another two and a half centuries; they were forced to move further and further into the desert in order to escape the notice of the authorities. Nevertheless, they refused to allow their religion to die entirely.

Alexandria remained a strategically important city until the final stages of the Crusades; it was still the country’s busiest port. The city withstood one Crusader siege in 1167, but fell to an attack from the Franks of Cyprus in October of 1365 — an attack that marked the very last Crusader incursion into the Middle East. The Arab historian al-Maqrizi wrote about the horror that ensued after the Franks entered Alexandria:

The Franks took the people with the sword. They plundered everything they found, taking many prisoners and captives, and burning many places. The number of those who perished was beyond counting. They continued killing, taking prisoners and captives, plundering and burning from the forenoon of Friday to the early morning of Sunday.

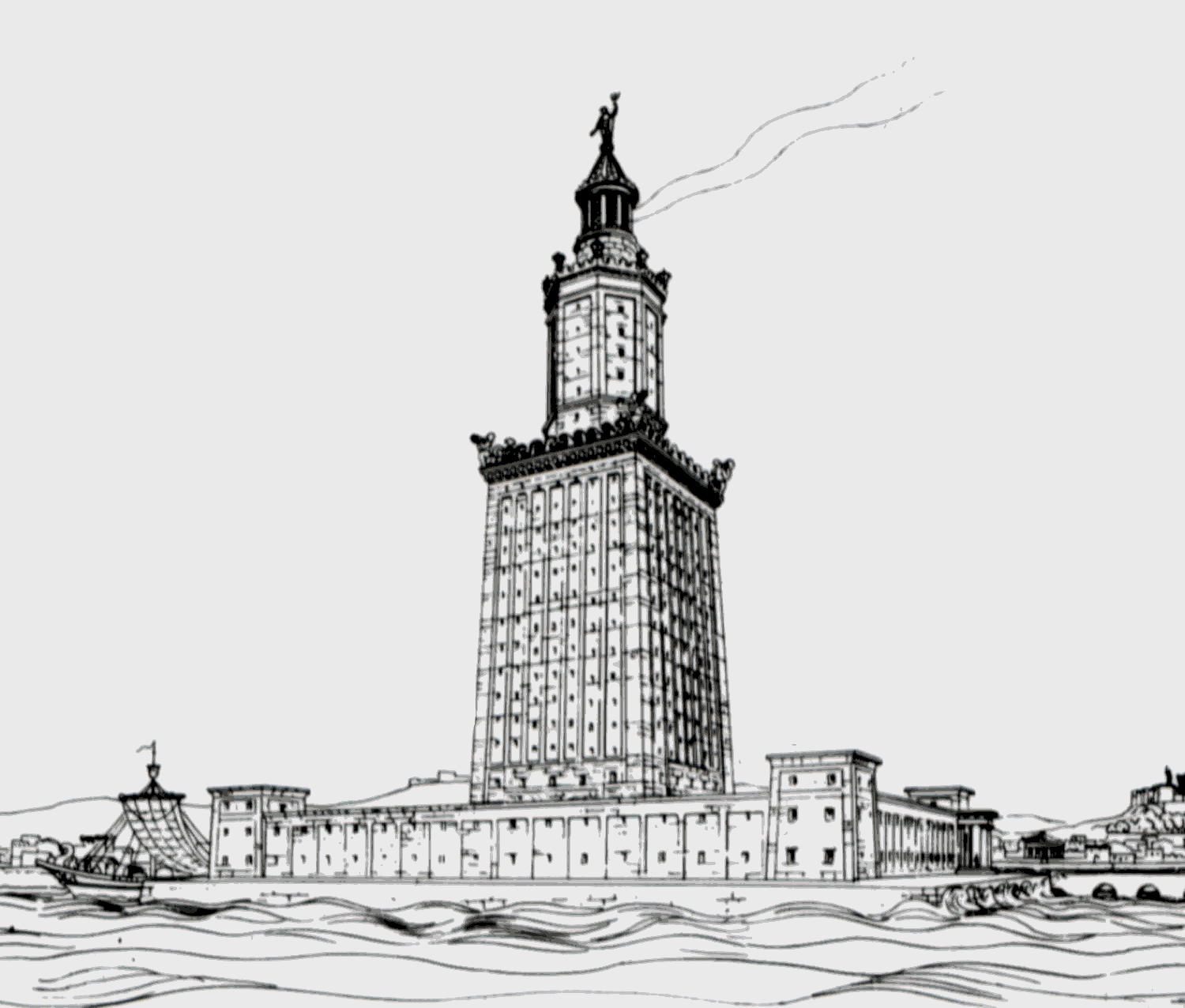

The Frankish Crusaders had no real plan for conquering more of Egypt. Facing an army marching up from the south which they couldn’t hope to defeat, they withdrew to sea again within a few days of landing in Alexandria. Yet their brief, bloody sojourn there marked the start of the final plunge for a city whose wounds from each successive blow since the great tsunami of AD 365 had been left largely untreated. In 1375, in an event fraught with symbolism, the Lighthouse of Alexandria — long since abandoned, rendered unsafe even to enter by centuries of battering by wind and sea — finally collapsed into the ocean.

Foreign commerce now shifted to other ports, and Alexandria was left to languish. Only fishermen, herdsmen, farmers, and soldiers stayed behind — the last because, even as the city proper died, it remained necessary to guard its superb harbor, a perfect location for an invasion fleet to anchor. Thus Qaitbay, the sultan of Egypt from 1468 to 1496, ordered a fort to be built on the very islet where the Lighthouse of Alexandria had stood for 1600 years. Scavenging many of their construction materials from the ruins of the lighthouse, the builders obliterated all above-water traces of Alexandria’s Wonder of the World. (The resulting Citadel of Qaitbay was what Vivant Denon would later refer to as the “Turkish fortress,” which Napoleon’s troops would easily overcome.)

The city of Alexandria’s downfall ironically coincided with the most magnificent period in the country of Egypt’s history since the heyday of the Ptolemaic Empire. Under the control of a Turkish warrior caste known as the Mamluks since 1250, Egypt had become a force to be reckoned with in the world once again, even as its Islamic culture was reaching towering peaks in literature, art, architecture, science, philosophy, and theology. Now, though, the focal point of all this activity was not Alexandria but Cairo. A wide-eyed visitor to the Egyptian capital named Ibn Khaldun wrote of his experiences circa 1400:

Cairo, metropolis of the world, garden of the universe, meeting place of nations, human anthill, heart of Islam, seat of power. Here are palaces without number, and everywhere flourishing madrases and khanqahs, while its scholars shine like dazzling stars. The city stretches over the banks of the Nile, river of paradise and receptacle of the rains of heaven, whose waters quench men’s thirsts and bring them abundance and wealth. I have walked its streets: they are thronged with crowds, and the markets are overflowing with every kind of merchandise.

Similarly, a traveler named Ibn Battuta called Cairo the “mother of cities”: “mistress of broad regions and fruitful lands, boundless in multitude of buildings, peerless in beauty and splendor, the meeting place of comer and goer, the halting place of feeble and mighty, whose throngs surge as the waves of the sea, and can scarce be contained in her for all her size and capacity.”

This halcyon period ended when the Ottoman Empire claimed Egypt for itself in 1517. Thanks to their Turkish roots, the Mamluks were allowed to continue to govern, but must now swear their allegiance to the Ottoman sultan, whose seat of power was none other than the old imperial city of Constantinople, a part of the Islamic world since the belated end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. In their latter days, the Mamluks of Egypt grew ever more debased and self-defeatingly tyrannical. Irrigation, that most essential prerequisite to life in this arid country, regressed until Egypt’s agricultural production was far less than it had been under the pharaohs, to say nothing of its time as the breadbasket of the Roman Empire. The results were waves of famine and disease and a hollowing out of a once-vibrant culture. By the time of the French invasion, Egypt as a whole was scarcely in better condition than Alexandria. The world had passed both by.

Napoleon’s army made short work of the Mamluk forces in Egypt, but his larger program of “civilizing” the country barely had time to get started. The French and all of their Enlightenment toys were driven out of Egypt by an alliance of the British and Ottomans within a few years. By that time Napoleon himself had abandoned his dreams of eastern empire in favor of conquering Europe; the last battle of his Egyptian campaign, like the first, was fought amid the ruins of poor, long-suffering Alexandria, but this time without his personal involvement. The mad scramble for control of Egypt that followed was won by Muhammad Ali, an Albanian tobacco merchant who had organized and led an army against the French. He ruled in Cairo from 1803 to 1848, officially in the name of the increasingly weak, decadent Ottomans in their far-off capital, but effectively as a sovereign monarch unto himself.

Muhammad Ali was no self-styled philosopher king in the mold of Alexander the Great or Napoleon. He was rather an unashamedly brutal despot who taxed his people to the ragged edge of starvation and used mass murder as an instrument of policy whenever he felt it necessary, who was functionally illiterate and never bothered to learn even spoken Arabic. But he was also a wily pragmatist who recognized that in order to survive — much less thrive — Egypt needed to modernize itself, needed to forge ties with the ascendant nations of Europe. And this redounded directly to the benefit of two entities of particular interest to us: what was left of the Coptic Christian community, and what was left of Alexandria.

Muhammad Ali’s despotism didn’t extend to the worship practices of Egypt’s citizenry — especially not when he had something to gain by refraining from persecution. And this he most definitely did in the case of his Christian subjects: with the old disputes over monophysitism and its opposite either forgotten entirely or relegated to the status of literal ancient history in the minds of most, the Western investors, entrepreneurs, adventurers, tourists, and missionaries who now began to arrive in Egypt in numbers saw the Coptic Christians not as an heretical sect to be crushed but as an enchanting time capsule of Christianity’s earliest centuries. Their donations helped the Coptic Christians to come in from the desert. Although the missionaries’ dream of a mass reversion to Christianity on the part of Egypt’s general population has never become a reality — the country is still 85 to 90 percent Muslim today — the spirit of religious tolerance introduced by Muhammad Ali has survived more or less consistently right to the present day, enough so to make Egypt the predominantly Muslim Middle Eastern country with the largest Christian minority. The Coptic Orthodox Church still exists as an independent institution today, with about 10 million members worldwide. And it still justifies its name by holding fast to its Coptic rather than Arabic or Latin liturgy. Ditto its monophysitism; the latter remains the primary doctrinal difference between the Coptic Christian Church and other branches of Christianity, even as it also remains a term that very few Christian believers can even define, much less take a firm stand about one way or the other.

Muhammad Ali lacked his predecessors’ antipathy toward Alexandria as well. He saw only its potential to become Egypt’s once and future gateway to the world, thanks to a harbor that was still as magnificent as ever and the aura that still clung to its name in the West. He thus became the founding father of the modern city of Alexandria, a true heir to the legacy of Alexander the Great in this respect at least. He cleared and repaved the city’s streets, re-dredged its canals, rebuilt its quays, and even erected a new lighthouse, not so spectacular as the old one but more than effective enough for guiding a new generation of commerce to Egyptian shores. He built a new shipyard right in the harbor, and designated Alexandria the home port for the modern naval and merchant fleets he intended to construct there.

In 1847, the British Egyptologist John Gardner Wilkinson published A Handbook for Travellers in Egypt, one of the world’s first tourist guidebooks. Therein he told of an Alexandria that was busily erasing its past in the midst of its headlong flight toward the future.

Little now remains of the splendid edifices of Alexandria; and the few columns, and traces of walls, which a few years ago rose above the mounds are no longer seen. A short time since, three granite columns stood on what was one of the large streets. The base of another remained in December, 1841, and was then broken to pieces; and the sites of these and others will in a few years be a matter of uncertainty. Much of course might be done to ascertain the direction of the streets, the position of the principal buildings, and the general plan of the ancient city, by tracing the form of the substructions, and the sites of the numerous arched reservoirs, that once formed a sort of subterraneous town, and doubtless took their position from that of the buildings above. But this would require extensive excavations, and the removal of the large mounds that have accumulated over them; and the number of modern edifices building there will soon make it impossible.

Wilkinson’s pessimism about Alexandria’s archaeological future was well-founded. Alexandria captured the attention of no Heinrich Schliemann, Flinders Petrie, or Howard Carter, and captured no international headlines during the heady era of archaeology that names such as theirs still evoke today. For the new city that was built over the ruins of the old did indeed make serious excavation there impossible; to this day we know far more about the layouts of many far less important ancient towns than we do of this one.

Muhammad Ali succeeded in realizing that ultimate goal of any despot: he passed his position on to his son, thereby becoming the founder of a dynasty. Although his successors proved somewhat less energetically committed to the thoroughgoing modernization of Egypt than their forefather had been, Alexandria’s rebirth had built up a momentum of its own. In 1856, Egypt’s first rail line was completed; it linked Alexandria and Cairo, thereby cementing the former’s status as the second city of Egypt, its window and its doorway to the world.

The years that followed brought hordes of well-heeled foreign tourists to Alexandria on posh new steamships, a gratifying echo of the ancient Romans who had once come in such numbers to sail up the Nile in much the same style and take in many of the same sights. A young Mark Twain was among this new breed of tourists. His travelogue relates an incident guaranteed to wound the psyche of any modern-day archaeologist to the quick.

[We] went in picturesque procession to the American Consul’s; to the great gardens; to Cleopatra’s Needles; to Pompey’s Pillar; to the palace of the Viceroy of Egypt; to the Nile; to the superb groves of date-palms. One of our most inveterate relic-hunters had his hammer with him, and tried to break a fragment off the upright Needle and could not do it; he tried the prostrate one [by this point, one of the three Needles had already been shipped to Paris] and failed; he borrowed a heavy sledge hammer from a mason and tried again. He tried Pompey’s Pillar, and this baffled him. Scattered all about the mighty monolith were sphinxes of noble countenance, carved out of Egyptian granite as hard as blue steel, and whose shapely features the wear of five thousand years [sic] had failed to mark or mar. The relic-hunter battered at these persistently, and sweated profusely over his work. He might as well have attempted to deface the moon. They regarded him serenely with the stately smile they had worn so long, and which seemed to say, “Peck away, poor insect; we were not made to fear such as you; in ten-score dragging ages we have seen more of your kind than there are sands at your feet: have they left a blemish upon us?”

The flow of tourists was briefly interrupted in 1882, when, following a period of internal unrest over the building of the colossally expensive Suez Canal, a native military junta wrested control of Egypt away from the dynasty of Muhammad Ali. Alarmed by this chaos, the British government sent a fleet to Alexandria to bombard and then occupy the city, marking the last time to date that it has been under direct attack. Determined to maintain order and keep the Suez Canal open at any cost, Britain restored the dynasty to power, but considered Egypt to be an only nominally independent “protectorate” thereafter. British involvement in almost every aspect of Egypt’s internal affairs would be a fact of life for the next 70 years.

In the long run, these developments were more to the advantage than the disadvantage of the burgeoning international city of Alexandria. Some portion of the foreign tourists who were soon arriving in larger numbers than ever wound up staying, and the result was a remarkable second flowering of Alexandria as a uniquely multicultural, cosmopolitan melting pot. By 1917, its population was 435,000, of whom 70,000 were foreigners: Greek, British, French, Armenian, Syrian, Italian, Lebanese; Jews had begun to return in considerable numbers as well. Once again, you could hear the babble of half a dozen languages in the course of one city block. An Armenian socialite who went by the name of Jacqueline Carol described “wide streets flanked by palm and flame trees, large gardens, stylish villas, neat new buildings, and above all, room to breathe. Life was easy. Labour was cheap. Nothing was impossible, especially when it involved one’s comfort.” The expatriate community watched the performances of a first-rate company at the Alexandria Opera House, saw the latest movies from all over the world at the Rialto Cinema, drank cocktails in the drawing rooms of Egyptian princesses.

When not hobnobbing, beach-combing, or navigating deliciously messy love lives, some of Alexandria’s privileged expatriates wrote. Constantine Cavafy, the greatest Greek poet of the last two centuries in the eyes of some students of literature, was born in Alexandria in 1863 and lived there until his death in 1933. His languidly melancholy verse blends the Alexandria of ancient times with the modern city he knew, often within the same stanza. Consider what is perhaps his most famous poem, “The God Abandons Antony” — Marc Antony, that is, holed up in Alexandria after the shame of the Battle of Actium, waiting for the final assault from Octavian.

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive — don’t mourn them uselessly.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving.Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

as is right for you who proved worthy of this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion, but not

with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen — your final delectation — to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

Cavafy became fast friends with the British novelist E.M. Forster, who arrived in Alexandria in November of 1915 as a Red Cross volunteer in anticipation of a Turkish invasion of Egypt that never came and stayed until January of 1919. Forster’s love for the city was such that he wrote two non-fiction books about it. Both he and Cavafy were gay, and found a safe haven in Alexandria; amazingly for a city in the Muslim Middle East, it was one of the safest places in the world to be “out” during the first half of the twentieth century. (It’s claimed that it was actually in Alexandria that Forster first consummated a romantic relationship, with a handsome young tram driver.)

But then, Alexandria wasn’t really a Middle Eastern city in spirit at all if Forster was to be believed:

Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Tolstoy — they must in the nature of things spring from a less cosmopolitan society. But what coastal Egypt can do and from time to time has done is to produce eclectic artists, who look to inspiration from Europe. In the days of the Ptolemies they looked to Sicily and Greece, in the days of St. Athanasius to Byzantium, in the 19th century it seemed they would look to France. But there was always this straining of the eyes beyond the sea, always this turning away from Africa, the vast, the formless, the helpless and unhelpful, the pachyderm.

In 1941, a journalist, travel writer, and novelist named Lawrence Durrell, another child of the British Empire displaced by a world war, washed up in Alexandria from Nazi-occupied Greece and stayed there until the war was over. Twelve years later, he published the first volume of The Alexandria Quartet, a series of four lugubrious, erotically charged novels in which, in the words of the author, “only the city is real.” Durrell’s Alexandria is a place of tired, sensual decadence haunted by the ghosts of its many prior incarnations. For its European inhabitants, it’s both an escape from a world at war and its own sort of prison. The tragic spirits of Antony and Cleopatra loom as large for Durrell as for Cavafy.

Notes for landscape-tones… Long sequences of tempera. Light filtered through the essence of lemons. An air full of brick-dust — sweet-smelling brick-dust and the odour of hot pavements slaked with water. Light damp clouds, earth-bound, yet seldom bringing rain. Upon this squirt dust-red, dust-green, chalk-mauve and watered crimson-lake. In the summer the sea-damp lightly varnished the air. Everything lay under a coat of gum.

And then in summer the dry, palpitant air, harsh with static electricity, inflaming the body through its light clothing. The flesh coming alive, trying the bars of its prison. A drunken whore walks in a dark street at night, shedding snatches of song like petals. Was it in this that Anthony heard the heart-numbing strains of the great music which persuaded him to surrender for ever to the city he loved?

The sulking bodies of the young begin to hunt for a fellow nakedness, and in those little cafés where Balthazar went so often with the old poet of the city, the boys stir uneasily at their backgammon under the petrol-lamps: disturbed by this dry desert wind — so unromantic, so unconfiding — stir, and turn to watch every stranger. They struggle for breath and in every summer kiss they can detect the taste of quicklime…

Alluring images like these must come complete with the same reservation that should be attached to virtually every version of Alexandria we’ve met in these pages: the reality that Durrell’s experience of Alexandria was a foreign rather than an Egyptian one. Cavafy, Forster, and Durrell never troubled themselves to learn the language of the people whose country they lived in, but rather laughed uproariously at the “Gippo English” of the porters and servants they hired, as if these Others were the ignorant ones. Durrell calls the less desirable areas of the city its “dark Arab-smudged streets,” and blames the native prostitutes for the venereal diseases that run rampant through the population of foreign layabouts like himself. The nostalgia that he and others express for the Alexandria of the first half of the twentieth century is, noted Laurence Deschamps-Laporte recently, “limited in reach, and loaded with ethnic and classist connotations”: “To reminisce about the cafés full of Europeans (from which non-elite local Egyptians were most likely banned), taxi drivers speaking Greek, and British sailors stopping in the port city for some comfort, is to actively ignore the history of the majority of Alexandrians.” This is, of course, a charge of which I too have been guilty again and again in writing this book.

But the twentieth century was not ancient times, and native Egyptians of that period proved less willing than their ancestors to suffer indefinitely the indignities heaped upon them by outsiders. A deep well of resentment finally burst to the surface in 1952, in the form of an ethno-nationalist revolution which toppled Egypt’s bloviated, irredeemably corrupt King Farouk and replaced him with the trim figure of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the first 100-percent ethnically and culturally Egyptian ruler of the country since Pharaoh Nakhthorhes. The new regime didn’t look favorably upon Alexandria’s insular expatriate community, especially after Britain, France, and Israel launched a brief, abortive war against Egypt in 1956 in a fruitless effort to restore the colonial status quo. Most of the foreign residents of Alexandria were expelled by the mid-1960s. Especially poignant was the deportation of the Jews, what with their millennia-bridging history in the city. When Alexandria’s last synagogue was rededicated in 2020, a congregation numbering all of three people was present for the occasion.

In 1977, a BBC film crew accompanied Lawrence Durrell back to the city that had spawned his most acclaimed novels. Acting every inch the aging imperialist, he kvetched about the posters outside the old Rialto Cinema, all printed now in incomprehensible Arabic: “In our time, film posters were billed in several languages.” (One does have to wonder if he complained at similar length about the monolingual English posters in his home country…)

So, Alexandria has been returned to the people of Egypt since the revolution. Its current inhabitants are only too happy to offer up an entirely different narrative of its history than the one I’ve presented in this book. Consider what one local said to the travel writer Tony Perrottet in 2002: “We were taught in our schools to call the time before Islam the Age of Ignorance.”

Whether more or less ignorant than it used to be, the new Alexandria has continued to grow in size and importance. With a population of some 5 million souls, it now dwarfs the ancient city at its peak, and stands today as the busiest port in the Mediterranean, a vital international conduit not only for food but for the oil that reaches it via pipelines from all over the Middle East.

And yet the memory of the less prosaic things that another incarnation of Alexandria was known for is not without resonance within an Egypt still struggling, fitfully and often misguidedly, to join the ranks of the so-called “developed” world. In recent decades Alexandrian archaeology, for so long an oxymoron, has been enjoying an unexpected revival as an aquatic pursuit, thanks to the realization that as much as 100 yards (90 meters) of what used to be desirable coastal land is now underwater. Divers have been discovering a veritable ancient wonderland under the waves, including sunken ships of all descriptions, a palace where Cleopatra may once have lived, and even chunks of limestone and granite that may have fallen off of the crumbling ancient lighthouse during its final decades. The Egyptian government has been talking for years about creating some sort of “underwater archaeological park” in the harbor, complete with submarine tours, but the finances and logistics have proved daunting; among other problems, the waters around Alexandria are miserably polluted.

One other grandiose monument to Alexandria’s past, however, has been brought to fruition. During the 1980s, Egypt’s president-for-life Hosni Mubarak launched a campaign to build a Bibliotheca Alexandrina — more commonly known in English as the New Library of Alexandria. Governments and private donors across North America, Europe, and the Middle East were inspired by the hallowed name to contribute $220 million to the cause. The finished complex, which opened in 2002, is a monument to internationalism; its striking granite façade is covered with the alphabets of the world. Inside is space for 8 million books, along with four museums, countless freestanding exhibits, and even a planetarium to celebrate the proud legacy of Alexandrian astronomy. It is, noted James Traub in an article for Foreign Policy magazine, “the one interior space in Alexandria that is elegant, clean, shiny, and welcoming.” So far, the New Library of Alexandria has weathered the volatile politics of Egypt relatively unscathed; amidst the tumult of the Arab Spring in 2011, student volunteers linked arms around the complex to protect it from the rioters who were trying to burn down anything that bore any taint of Mubarak’s autocratic regime.

How should we see this New Library of Alexandria? As the earnest monument to learning and cross-cultural dialog which it professes to be? Or as one more useless monument to one more useless Middle Eastern autocrat’s vainglory, a tragic white elephant in a country still plagued by poverty and countless other basic social ills?

For that matter, how should we see Alexandria’s larger history? As a story of progress begun and then derailed? Or as a story of colonialism before that word was invented, of exploitation and racism? This book has hewed to the former interpretation, a very traditional Western one. (“In the Western imagination Alexandria has always been associated with loss,” writes the very unnostalgic Middle Eastern historian Khaled Fahmy.) Another, perhaps better — or at least bolder — book might choose another tack.

Still, the traditional Western take on Alexandria’s history continues to resonate with us today for a reason. If we can set aside for a moment all of those dangerous “-isms” with which it is associated, we can see ancient Alexandria as the incubator of the modern liberal worldview. Both modern science and modern religion, those two uneasy bedfellows, were to a large extent invented in Alexandria. The contributions of the former are obvious and often championed by a certain strain of writer, too frequently as a way of bludgeoning the latter. Yet we should not dismiss Christian Alexandria out of hand. Our liberal ideals about the sovereignty of the individual have their roots not in any sort of empiricism but in the Christian concept of salvation as an individual choice; at bottom, they are an exercise in faith rather than reason. The liberal worldview, in other words, is a combination of both halves of ancient Alexandria’s character; this remains true regardless of one’s view of the literal truth of Christian teachings, or one’s position on the ongoing need for them in the modern world that we live in. Yes, we need our great minds in order to build a brighter future, but we also need our great souls. Indeed, it sometimes seems to me that the latter are in far shorter supply than the former.

For I write these words at a moment in history when illiberalism — what we might call the anti-Alexandrian point of view — is on the march again in many parts of the world. It’s therefore more important than ever that we not forget the other great lesson of the traditional Alexandrian narrative: that earnest argument can all too quickly yield to imposed dogma, that a Clement can succumb to a Cyril. So, let us take that lesson to heart and defy the Cyrils of our world. Let us never “say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving” — “the Alexandria you are losing.”

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Jaina

Nor did Muhammad Ali didn’t share his predecessors’ antipathy toward the city”

Heck of a ride. Love the book, thank you.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Andrew Pam

“Muhammad Ali’s despotism didn’t extent to the worship practices of his citizenry — especially not”

Should be “extend”, and an accidental extra line break.

Andrew Pam

“the time before before Islam” – doubled word.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Phil B.

Fantastic series. Thanks so much for writing it.

David Boddie

An excellent conclusion to the series! It rounds off the book very well.

Will Moczarski

in the mold Alexander the Great or Napoleon

-> mold of

Nor did Muhammad Ali did share

-> Nor did Muhammad Ali share

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Patrick Lam

Found one! predominately -> predominantly. Looking forward to reading more about Rhodes (which I’ve spent a couple of days on and found sort of over-touristed…)

Jimmy Maher

Thanks! Modern Rhodes is a notorious tourist trap, but it has a fascinating history all the same…