A pair of fairly breathtaking political realignments was occurring in the eastern Mediterranean while the Colossus of Rhodes was being planned and erected. The empire of Rhodes’s recent antagonist Antigonus imploded like a popped balloon in 301 BC, after a decisive military defeat and the death of its monarch at the hands of a coalition of the enemies he had been assiduously collecting. Undaunted, Antigonus’s son, Rhodes’s personal nemesis Demetrius, secured a new empire for himself in 294 BC by murdering the current king of Macedonia and taking his place.

By the time the Colossus was completed, the world around Rhodes had settled into a relatively stable tripartite order: Ptolemaic Egypt dominating to the south of the island, the Seleucid Empire to its north and east, Macedonia to its west.

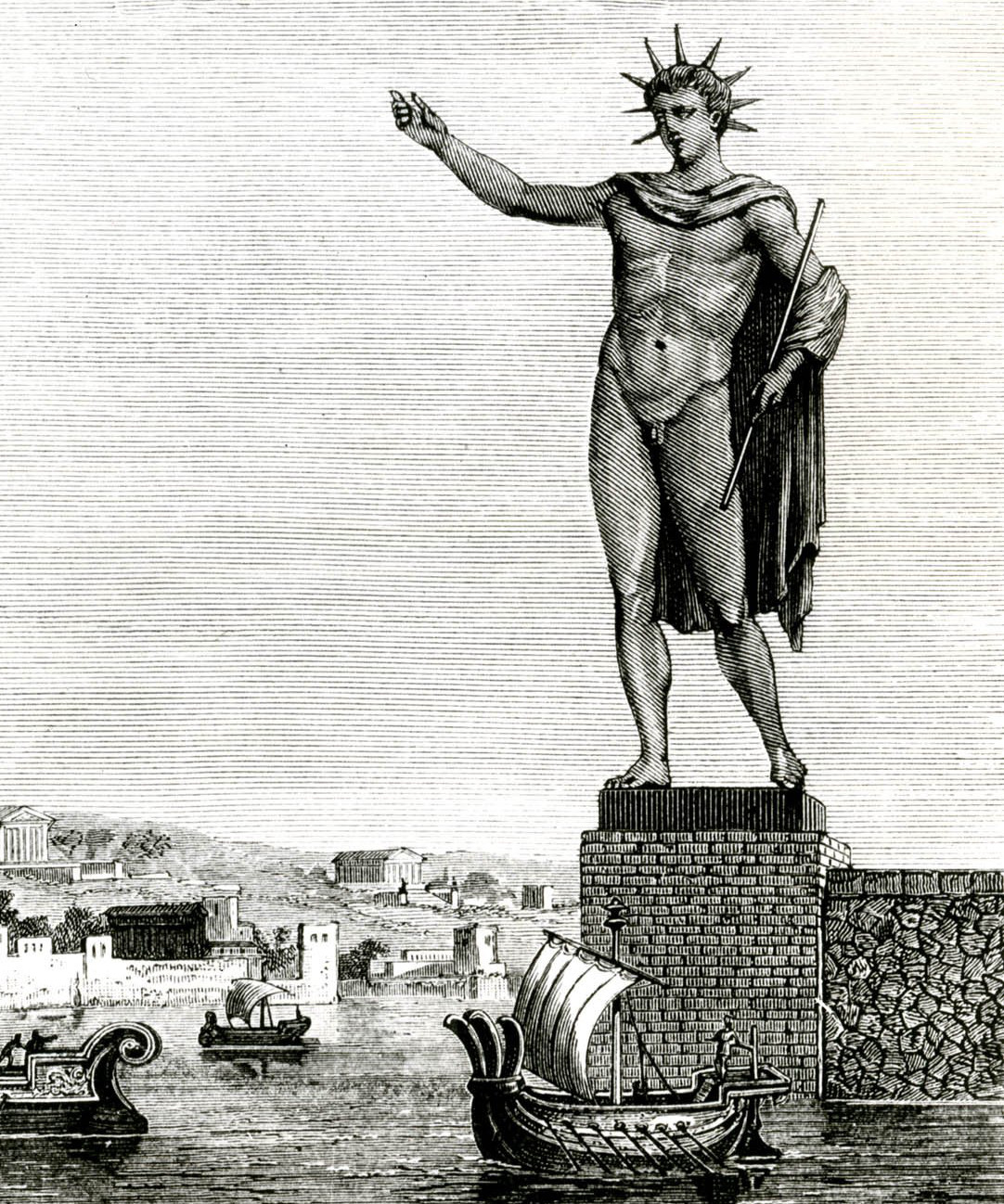

The 56 years during which the Colossus stood upright on Rhodes ironically correspond with something of a black hole in our knowledge of the geopolitics of the Mediterranean. We have to go back to the time before the Greco-Persian Wars to find a period about which fewer ancient chronicles have survived. This paucity of material does much to explain why we have just one first-hand account of the Colossus that was written while it was still standing, despite what a truly wondrous sight it must have been, one well worth writing about. From the little we do know about the period, it would appear that the only major disruption to the established order over the course of it was the rise of a Kingdom of Pergamon, which began as a rump state of the Seleucid Empire and gradually secured full independence. Thus the tripartite order became in time a quadripartite one.

Everything else we know about these decades would indicate that they were a time of particularly great wealth and influence for Rhodes; the best modern comparison to the Rhodes of the third century BC might be the Southeast Asian city-state of Singapore. With a stable government at long last, the island was better equipped than ever to be one of the principal crossroads of the Greek world. In addition to its ongoing importance for the international grain trade, Rhodes became a hugely important banking center as coinage replaced barter- and credit-based systems of trade all over the Mediterranean. Rhodes grew so wealthy that it was able to buy some modest territories of its own on the nearby Mediterranean coast of Asia, probably for the purpose of securing a steady food supply to feed its growing population. By no means was the island entirely exempt from the back and forth of alliances and wars, but the empires around it treated it with kid gloves on the whole. Its functions as a meeting place and trading and financial center in a perpetually feuding world made an independent Rhodes more valuable than the alternative to just about everyone. Meanwhile, a divided but settled world order being best for business, the Rhodians themselves had a vested interest in ensuring that no single empire got too big for its britches. It seems that they used their wealth freely to promote this agenda, funding a rebellion against a tyrant here, withholding credit from a disrupter of seaborne trading routes there.

Perhaps the greatest testament to Rhodes’s status in its world was said world’s reaction to the terrible earthquake that struck the island in 226 BC. We have no firsthand accounts of the earthquake itself or the destruction it caused — including, of course, the toppling of the Colossus, which must have been a well-nigh apocalyptic thing to witness. But we do know that an unprecedented international effort was mounted to relieve the island’s suffering and restore it to its former glory. Almost all of the lands of the eastern Mediterranean, large and small, contributed to the cause, donating lead, pitch, timber, grain, silver, hair, resin, bronze, even catapults to restore the harbor defenses, while human resources in the form of builders and masons and other craftsmen also arrived in large numbers to help the Rhodians make use of it all. As is so often the case with such things, the donors’ motivations weren’t completely altruistic; they needed Rhodes to continue to play its unique role in the world as much as Rhodes needed them in this, its moment of crisis. “There are few more impressive signs of the extent of Rhodian economic influence,” writes Richard M. Berthold, “than the reaction to the earthquake and the ease with which the Rhodians elicited the simultaneous support of the [other] ever contentious powers.”

The foreign aid was so generous that there surely must have been enough of it to set the Colossus back on its feet, had the Rhodians been determined to do so. Strabo tells us, as we learned in our first chapter, that the statue was left lying where it fell thanks to an oracle who “prohibited its being raised again.” This brief statement has provoked much speculation over the years. Presumably the prohibition was accompanied by a prophecy of doom — another, even worse earthquake? — if it was ignored. Was the mouth from which it issued that of the oracle at Delphi, the most respected in the world? It’s hard to believe that the Rhodians would have listened to such an inconvenient commandment from anyone else.

Then again, perhaps we’re looking at it all wrong. Lawrence Durrell cheekily notes that the injunction might in fact be read as all too convenient for the pragmatic Rhodians, being an excuse for them to avoid spending a big portion of their relief money on rebuilding their useless Colossus, only to watch it fall over again when the next earthquake hit. Perchance they “came to some underground arrangement with the priests of the oracle in order to provoke such an announcement and be free from the irksome necessity of rebuilding the Colossus.” Such an arrangement wouldn’t be out of keeping with the tenor of the times. By the late third century BC, oracular pronouncements and the like were taken much less seriously than they once had been, and even the famed Oracle of Delphi had become more of a prop for political theater than any testament to an ongoing faith in the direct participation of the gods in the affairs of ordinary humans.

At any rate, the Colossus was left where it fell, still a spectacular sight in its way, and the life of Rhodes went on around it. By all indications, the town and its harbors were rebuilt as quickly as anyone could have hoped, and were little worse for wear a decade or two after the earthquake, one toppled statue of the sun god aside. The historical record begins to pick up again at this point — not coincidentally, at just the instant when a dynamic young power known as Rome entered this aging Greek-speaking milieu.

By this time, the stability that had marked the last half-century and change in the eastern Mediterranean was beginning to break down at long last. Egypt, Rhodes’s most loyal friend and benefactor of all, had slipped into a marked decline, the product of a flabbergasting level of decadence and corruption inside the Ptolemaic court. Under King Philip V, the great-grandson of Demetrius the besieger of Rhodes, the Macedonians were rushing to fill the resulting vacuum; they had come to utterly dominate the trade routes of the Aegean Sea, and were now pressing into the mainland of Asia Minor. The Rhodians, whose economy and perhaps even political independence depended on none of the four empires around them getting so strong that it could run roughshod over the others, were not at all pleased by these developments.

Indeed, credible reports claim that the Rhodians actually traveled to Rome and begged its leaders to move east and cut Philip V back down to size. If these reports are correct, the Rhodians got all they had asked for and then some. In the years between 200 and 196 BC, Rome rolled up the entirety of the Macedonian Empire with the support of the Rhodian navy, forcing Philip to sign a peace treaty that made himself and his empire into Roman vassals. Rhodes emerged from the war seemingly stronger than ever; it had secured a new, much more mighty friend and benefactor in Rome than Egypt had ever been, and was rewarded with some juicy plots of former Macedonian land. Nevertheless, the entrance of Rome into this part of the world had altered the balance of power in ways that boded ominous for Rhodes’s longer-term future.

For Rome, having come this far, saw no reason to stop. It demanded a degree of subservience from the three remaining emperors in the region that would leave them little better off than Philip V. In 192 BC, King Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire attempted to assert his sovereignty militarily. The results were disastrous for him; in 188 BC, following a series of devastating defeats, he was forced to surrender to the Romans most of his territory west of Mesopotamia. The Rhodian navy once again aided the Romans in this conflict, although one has to suspect that this was a war the Rhodians would have preferred to leave unfought.

Ptolemaic Egypt and the Kingdom of Pergamon rushed to accede to all of the Romans’ demands in order to avoid the fates of Macedonia and the Seleucid Empire. Rather than a quadripartite order, ripe for the clever playing off of one side against the other in that way in which the savvy Rhodians had always excelled, Rhodes and all of its neighbors now lived at the sufferance of a single self-assured power, one destined to dominate the course of Western history for the next 700 years.

Rhodes too was eventually forced to accept the same subservient fate as the larger empires around it. Under extreme pressure from Rome, recognizing the reality that the Mediterranean as a whole had now become a Roman lake, Rhodes signed a treaty in 164 BC in which it surrendered its independence in matters of foreign policy along with all of its external territorial possessions to its new Latin overlords. It was a typically pragmatic, classically Rhodian decision, as noted by Richard Berthold:

With its long history of independence at an end, Rhodes hastened to give up the freedom that no longer existed and to secure the alliance it had forever avoided. Putting aside its pride, it accepted the humiliation; Rhodian independence might be dead, but the state could continue to live and prosper in the changed world. Many a Greek city had shown defiance in the face of even more hopeless odds, and there would have been satisfaction in seeing the cocksure attitudes of the [Roman] senators met with the same kind of resistance they would find fifteen years later before the walls of Carthage. But such a reaction, though noble, would have been one of emotion; ever rational, Rhodes chose submission.

In some ways, the story of the Colossus of Rhodes ends here, with the passing of the Grecian world order and the single proudly independent, proudly wealthy island nation within it that could produce so grandiose a monument to its glory as this one. But of course we have every reason to believe that the monument in question continued to lie there witnessing how Rhodes navigated the Roman world order that had replaced the Grecian.

And truth be told, some of the centuries it witnessed were pretty good ones. Rhodes remained a major trading and financial center for a long time, as described by the likes of Strabo and Pliny. The island also won renown among the Romans for its orators, a product of an intellectual tradition to which I’ve given less attention in these pages than it perhaps deserves. One story says that, when the great Roman general Pompey visited Rhodes, he made a special point of listening to its many street-corner philosophers, and bestowed a generous cash award upon those he most appreciated. Likewise, Brutus and Cassius, along with Pompey the other eventual losing antagonists to Julius Caesar in the civil war that transformed Rome from a republic to an empire in the middle of the first century BC, allegedly studied rhetoric on Rhodes as young men.

In AD 44, the Roman Emperor Claudius officially ended the last vestiges of Rhodian autonomy along with its 350-year-old democracy, placing the island under the direct control of the nearest Roman provincial governor on the Asian mainland. We need not dwell overmuch here on the centuries that followed, when Rhodes’s history mirrored that of the empire to which it now belonged: a time of peace and prosperity such as the world had never known shading into the long, slow decline so memorably chronicled by Edward Gibbon and others. After AD 400, the Roman Empire was split in two, and Rhodes became a part of the Byzantine Empire, which ruled the eastern half of the former monolith from Constantinople.

The Colossus of Rhodes is absent from the historical record for more than 850 years after Pliny writes of it circa AD 70, only to unexpectedly pop up again in one of the texts attributed to Constantine VII, a Byzantine “scholar emperor” of the tenth century. He states that the Colossus still remained on Rhodes as late as AD 653. At the latter date, a new power was on the march from the heretofore little-remarked Arabian Peninsula of Asia, fueled by a messianic new religion known as Islam. It had already seized Egypt and other territories from the Byzantines, and had its eye on yet more.

According to Constantine VII, Caliph Uthman of the Arabs, son-in-law to the deceased prophet Muhammad himself, sacked Rhodes in AD 654. The scholar emperor tells us that “his general was named Mavias, and it was he who overturned the Colossus of Rhodes. He stripped it of its bronze and, taking it to Syria, put it up for sale to anyone who wanted it. A Jewish merchant from Edessa bought it, and loaded the bronze onto 900 camels.”

Michael the Syrian, patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1166 to 1199, provides a more detailed account of the same events, albeit from an even farther remove in time:

[The Arabs] went to Rhodes and devastated it. The Colossus of bronze was a fine work, and was reckoned one of the Wonders of the World. They set about breaking it up in order to carry off the bronze. It has the pose of standing man. When they put fire to it they saw that it was fastened to stone in the earth by great bars of iron. With great ropes numerous men pulled on it, and suddenly it turned over and fell to earth.

Both accounts give us reason for skepticism in the way that they fail to jibe with what Strabo and Pliny have already told us. Most obviously, both describe the Colossus as still standing upright some 875 years after Pliny tells us it was toppled. The indefatigable Herbert Maryon tried to reconcile all of the texts in 1956 by imagining a Colossus that broke at the knees — the weakest point of almost any sculpture of an upright human being — during the earthquake of 226 BC:

I think that we can see what happened. The earthquake overturned the Colossus. The stone and iron columns buckled at the knees. The upper part of the statue fell right over, and the head and shoulders reached the ground. But the marble base and the legs up to the knees stood firmly, with the body and head half hanging down from them, half lying on the ground. The iron supports had bent but had not broken, though the stone columns and the bronze sheathing had. The broken figure, supported at the knees, would be 50 or 60 feet [15 to 18 meters] high, as tall as a six-storey house.

As much as I generally respect the arguments of the venerable bronze-working expert, I must confess that I find it far easier to believe that Constantine VII and Michael the Syrian were simply confused. And if they were confused about so important a detail as this one, it does rather throw their whole account into question.

Another, subtler discrepancy also turns up in the tale of Constantine VII. Note his statement that it took 900 camels to cart all of the bronze away. A credible estimate for the amount of weight one camel might carry is about 800 pounds (360 kilograms). If we do the math, then, we wind up with over 320 tons of bronze being hauled away. Contrast this with Philo’s claim that only 12.5 tons of the stuff went into the statue!

Further, Rhodes would appear to have been only briefly sacked and occupied by the Arabs in AD 654; it was soon back under the control of the Byzantines, who still retained it when Constantine VII wrote his chronicle in the tenth century. Did the Arabs really have time to organize and carry out such a massive demolition-and-salvage project amidst all the other pressures of war?

In the end, there is nothing we can say with absolute certainty about the chronology of the fallen Colossus’s removal, beyond the fact that it must have been removed well before the tenth century. Stories of Muslim Arabs demeaning and despoiling the treasures of civilization are all too common in Christian accounts like those of Constantine VII and Michael the Syrian. (Not to mention the acquisitive, amoral Jew who profited from the endeavor…) It’s entirely possible, even probable, that every trace of the Colossus was long since vanished from Rhodes by AD 654. Surely as the world around the island slid into decline, the fine bronze, iron, and marble that had been used to build the Colossus would only grow that much more tempting, lying there ripe for the taking as they were on the ground.

The hard fact is that what we don’t know about the real Colossus of Rhodes dwarfs that which we do, and this situation is unlikely to change. Studying ancient history either builds a tolerance for ambiguities like these or sends one running to some other, more knowable era of the past. Regardless, the legend of this giant figure of Helios — this manifestation of “the lovely light of unfettered freedom” that was Rhodes for a time — remains an indelible part of our collective historical consciousness. Maybe this Colossus of the soul stands on the acropolis of Rhodes, maybe on a harbor-side mole, or maybe, if we must, he stands with legs proudly planted on two separate moles while ships sail underneath him. All of these visions have become part and parcel of him.

“Now the historical impact of [the Colossus’s] name is mixed with memories of this pure sunlight, these dancing summer days passed in idle friendship and humor by the maned Aegean,” wrote Lawrence Durrell in 1953, describing an experience to which many a more recent tourist to Rhodes, a blessed island of the sun with or without a statue of its god, can doubtless relate. “Who could ask for better?” Like any truly great figure of history, the Colossus of Rhodes seems destined to continue to inspire idle summer dreams forevermore — not a bad legacy for a life of just 56 years.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

morg

> In addition to its ongoing importance for the international grain trade, Rhodes became a hugely important banking center as coinage replaced the old barter systems of trade all over the Mediterranean.

David Graeber’s “Debt: The First 5,000 Years” makes the case pretty convincingly that the Smithian myth of barter is just that and ancient economies operated on systems of credit; pure barter just isn’t efficient enough to trade at any scale. Coinage appears in periods of centralization when governments have the political and military wherewithal to issue, guarantee, and accept (as tax) their own currencies, and disappears when they don’t as in the post-Roman era in western Europe.

Jimmy Maher

Fair enough. Edit made. Thanks!

Martin

OK I’ll bite, why did they do with the hair after the earthquake?

As to the Jew with the 900 camels, possibly it wasn’t the weight but the size of the bronze sheet that defined the need for 900 of them. If the statue was cut up into say 10×10 feet sections, it would be hard for a single camel to carry it one without it falling off. Maybe there was no Jew and 900 camels but that could be one way the camel numbers could make sense.

Jimmy Maher

I must confess that I don’t know what the hair would have been used for, just that it is described as being among the materials delivered to Rhodes after the earthquake.

Hair

The hair would have been for plaster, I’d imagine.

Jaina

given less attention in these pages that it perhaps deserves.” Than?

I can’t wait to see what wonder we get next 😁😁

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Will Moczarski

corresponds with something

-> correspond

[15 to 18 meters)

-> different kinds of brackets

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Michael Waddell

The period between Alexander the Great and the rise of Roman dominance is often given short shrift, both because of our lack of sources and because the Wars of the Diadochi are legitimately convoluted. This series has really shone a light on this period in particular. After all, it takes a strong and wealthy society to create a Wonder, so focusing on the great monuments naturally gives a clear impression of who the great powers of the period were (even if Alexandria and Rhodes aren’t as well known today by most people as Rome or Athens). I feel like I have a much rounder, more vivid understanding of the pre-Roman world because of this series, and I thank you for your efforts!

Peter Olausson

The Wonders of the World are like the top predators in an ecosystem – there’s much more to study, much of it more interesting than the wonders themselves, but they are great indicators that’s there’s indeed much more to study. Societies that don’t produce science, literature, poetry or whatnot don’t produce wonders. And the way this tremendous series describes the societies with their wonders as the focal points is truly wonderful.