Paul III was the last pope to seriously imagine that the second great schism in the history of Christianity could be healed, that a peaceful way could be found to bring Protestants back home to the Catholic Church. In 1536, as Michelangelo was beginning the painting of the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall in Rome and Henry VIII was executing his second wife in London in order to make space for a third, Paul proposed that both Catholic and Protestant luminaries assemble in the northern Italian town of Mantua to hash out their differences and reunite Western Christendom.

There had been a time, not all that far in the past, when such a papal proposal would have been taken as a veritable order from God. Alas, though, the times had changed. At the behest of Martin Luther, all of the Protestants who were contacted returned their letters of invitation unopened; the many disparate types and creeds of Protestantism may have agreed on surprisingly little, but none of them had any interest in becoming Catholics again. But for that matter, even the remaining Catholics of Europe proved recalcitrant. King Francis I of France and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, locked in their embrace of mutual loathing, both refused to send representatives to a council which the other’s representatives were also attending, even as both objected equally to the council being held outside of their own territory. Instead of heralding a new age of healing under the one true Christian Church’s one true pope, Paul’s call to dialogue only served to demonstrate to the world the limits of his reach in these latter days.

The meeting that did finally take place was as diminished in comparison to Paul’s original plans for it as it was belated. No Protestants nor any Frenchmen were present when it began on November 1, 1542, not in Mantua but in Trent, a city which, although Italian in language and culture, lay within the borders of Charles’s empire. With such paltry participation, it was hard to know what could be done, and the desultory talks soon petered out. Another three years passed, while Paul’s negotiators tried to convince a more diverse body of Catholics that it was worth their while to attend an ecumenical council. Progress was halting but real, what with the undeniable urgency of the Protestant threat. At last, on December 13, 1545, the Council of Trent opened for real, not as the broad-based attempted reconciliation between the two halves of Western Christendom that Paul had first envisioned, but as a place for Catholics to discuss the situation among themselves and decide how to avoid losing any more ground to the zealous heirs of Martin Luther.

The attendees concluded in fairly short order that the Holy Mother Church could not and should not hope to bring her wayward flock back into the fold through appeasement or compromise. To attempt to do so would only be to admit weakness, thus priming the Church for further losses. No, Catholicism could be rejuvenated only by becoming more Catholic in its outlook than ever. In its first major declaration, issued in April of 1546, the Council of Trent reaffirmed the Catholic Church as the sole vehicle of salvation for Christians everywhere and the pope as God’s chosen spokesman on Earth, as proved by Jesus’s famous words to his apostle Peter in the Book of Matthew. Only the clergy of the Church had the God-given right to explain and interpret the Bible, whose only valid, God-endorsed translation was the millennium-old Vulgate Bible of Saint Jerome. Christian theology beyond that which was to be found in the Bible had been crystallized by Saint Augustine and perfected by Saint Thomas Aquinas; there was no need for any more innovation on that front. After all, the rock of the Church was faith, not reason. In short, the Church had no truck with encroaching Modernity in any of its aspects.

Having come this far, however, the council broke down into in-fighting. A significant and growing faction within the Church insisted that clinging tighter to traditional Catholic theology in terms of rhetoric alone would not suffice to stop the bleeding, much less begin to reconquer the hearts and minds of the wayward flocks of Europe. For the people had grown disillusioned with the wink-wink, nudge-nudge attitude of the men of the Church — grown tired of greedy bishops, fornicating priests, malevolent monks, and, although no one dared to say this part out loud, of easy-living popes as well. The Church had to reform itself from within, along Catholic rather than Protestant theological lines, yes, but no less strictly for that. The men of God had to start to live their words again, to give the people good examples of Godly behavior to follow as well as fine speeches.

Needless to say, this was an unpleasant message for many of the clergy to hear. There are reports of physical altercations among bishops on the floor of the debating chamber, of attendees pulling one another’s beards and threatening to pitch one another bodily into the Adige River. Ironically, one of the least receptive to the call for reform was Pope Paul III, the very man who had caused the Council of Trent to happen in the first place. For, as we’ve seen, he was the farthest thing from any paragon of ascetic self-denial, preferring to keep the party going back in Rome like it was 1499 and Martin Luther was still just an unknown German schoolboy.

The city of Rome was actually regaining some of its civic mojo at the time. Even as the Church was losing its political and spiritual hold on large swaths of Western Europe, its financial situation was improving, thanks to a steady flow of tribute from staunchly Catholic Spain and Portugal, the fruit of growing empires in the Americas and East Asia. Paul used that flood of cash to restart Pope Julius II’s most ambitious project of all, the new Saint Peter’s Basilica. In 1546, when the first architect he had appointed to the project died, he turned to the 71-year-old Michelangelo.

On the face of it, it was an odd choice; Michelangelo had only dabbled in architecture to this point, and this was an awfully late date in life to be taking up a new artistic calling. Still, he was accustomed to working on a monumental scale, even as his reputation — the mixed reception of the Sistine Chapel altar wall notwithstanding — was such that anyone would have to think thrice before taking the commission away from him; this was surely a serious consideration for Paul, whose own time on Earth was growing short and who wanted to be remembered in connection with the cathedral as dearly as Julius had before him. For Michelangelo’s part, it must have pleased him enormously to have this chance to complete what his old enemy Donato Bramante had been unable to see through. He set to the task with a will, demolishing some of the work that had already been done at the site as unceremoniously as he had recently erased some of the older frescoes left behind by Pietro Perugino and even himself from the Sistine Chapel. Here as there, it was necessary in order to make space for his latest artistic vision; the cathedral was to be the crowning achievement of his long career. On his deathbed in October of 1549, Paul did his best to ensure that his court artist would continue to direct the construction effort after he was gone: “We appoint and commission him [Michelangelo] the prefect, overseer, and architect of the building and fabric of the Basilica on behalf of ourselves and of the Apostolic See for as long as he shall live.”

As it transpired, Paul needn’t have worried overmuch. His successor was Julius III, a man quite unlike the pope who had last borne that name, who thought first of his own comfort, letting affairs outside of his palace drift along in whatever way would disturb it as little as possible. So, Michelangelo continued to work, as did the Council of Trent in fits and starts, albeit with less obvious results.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles, the only monarch of Europe whose rule straddled Catholic and Protestant areas, was understandably eager to broker peace between the two factions of Christianity, for all that he would always be a Catholic in his heart of hearts. (Thus all those rich Church donations from his Spanish empire…) At his insistence, the Council of Trent allowed a Protestant delegation to speak on January 24, 1552. The occasion would go down in history as a melancholy landmark, the last time that Catholics and Protestants would meet and talk with one another as equals for four centuries. But it led nowhere. The Protestants delivered a series of rabble-rousing speeches which adjured everyone present to renounce the pope then and there. This very nearly got them killed on the spot, despite Charles’s promise of protection. The proceedings grew so acrimonious thereafter that no one could see a point to them anymore. The Council of Trent was formally suspended on April 28, 1552, having failed to accomplish much of anything beyond empty affirmations.

Three more popes passed away before it reconvened. Marcellus II was Holy Father for only 22 days in April and May of 1555, but Paul IV managed more than four obstinate years. He was in many ways the warrior pope for whom conservatives in the Church had been wishing for decades; the Florentine ambassador to Rome described him as “a man of iron, and the very stones over which he walks emit sparks.” Whereas Paul III was the last pope to imagine that a peaceful reunification of Western Christendom could be effected, his later namesake was the last one to fondly imagine that he could pull off the same feat by force alone.

He hectored the Catholic monarchs of Europe to launch Crusades against the Protestants, and took it with decidedly poor grace when they tried to explain to him that they lacked the resources and political capital to comply. For example, he labeled the devoutly Catholic but politically practical Charles a secret atheist, a “cripple in body and soul.”

Even as he labored fruitlessly to open new foreign fronts in the war against Protestantism, Paul set about stamping out any trace of doubt or unorthodoxy at home. He published the Church’s first universal Index of Forbidden Books, a lengthy list that included, alongside the expected likes of Martin Luther, Jan Hus, and John Wycliffe, 48 translations of the Bible into vernacular tongues. But he was careful to note that those books that were actually on the list were only the worst offenders. Catholics, he said, were not to read any book, whether on the list or off of it, that didn’t display on its frontispiece the Church’s official imprimatur: literally, “let it be printed.” Mass burnings of unauthorized books took place all over Catholic Europe. Venetian Catholics burned 10,000 books in a single day of feasting and celebration; the ranks of the destroyed included not only heretical theological texts and Bible translations but countless great works of pre-Christian Antiquity.

Enforcement of the new strictures was given over to a reinvigorated Inquisition, whose instructions were as uncompromising as they were explicit.

1. When the faith is in question, there must be no delay, but on the slightest suspicion rigorous measures must be taken with all speed.

2. No consideration is to be shown to any prince or prelate, however high his station.

3. Extreme severity is rather to be exercised against those who attempt to shield themselves under the protection of any potentate. Only he who makes plenary confession should be treated with gentleness and fatherly compassion.

4. No man must debase himself by showing toleration toward heretics of any kind.

Rome especially was convulsed by a reign of terror, less concentrated but no less appalling in its way than the recent sacking at the hands of German Protestants. “The hasty and credulous pope lent a willing ear to every denunciation, even the most absurd,” writes the historian of the papacy Ludwig von Pastor. “The Inquisitors, constantly urged on by the pope, scented heresy in numerous cases where a calm and circumspect observer would not have discovered a trace of it.” Anyone of an intellectual bent was suspect, bound to be hauled up before a tribunal sooner or later. By no means did this apply only to the laity; priests and cardinals and monks as well were condemned by the dozens, and in some cases burnt at the stake. “Even if my own father were a heretic,” said Paul, “I would gather the wood to burn him.” To prove the point, he did indeed order the Inquisition to arrest many of his own family and formerly trusted associates.

The ascension of Paul IV might have appeared to bode ill for Michelangelo, who was still plugging away at the new Saint Peter’s Basilica, although less effectively than he perhaps would have as a younger man. Paul had in fact been a founding member of the Theatines, the group of Church conservatives who had so roundly condemned Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. Yet even this fanatical pope seemed somewhat in awe of the old artist, the last living link to Italy’s previous century of promise and possibility. He left him alone to continue his work as he would.

When Pope Paul IV died on August 18, 1559, all of Rome erupted in celebration. A mob stormed the Inquisition’s headquarters to free all of the prisoners held inside, and a freshly erected statue of him was toppled and smashed to pieces.

His successor Pius IV was completely different, being thoughtful where Paul had been obstinate, conciliatory where Paul had been confrontational. He didn’t formally erase the Index of Forbidden Books and Paul’s many other laws and strictures, but he made it clear that he wished for them to be applied only to the worst cases of open heresy and rebellion; he told the Inquisition that it “would better please him were they to proceed with gentlemanly courtesy than with monkish harshness.” Legend has it that a reactionary who objected to Pius’s leniency was poised to assassinate the new pope as he passed by in the street, but wound up falling down at his feet to beg forgiveness instead, so overawed was he by the aura of holy benevolence that radiated from the man.

By the time of Pius’s elevation, Scandinavia, England, and a goodly part of Germany had already been permanently lost to the Church, and the Netherlands was teetering on the verge of becoming the next region to break away. The axes and bonfires of Paul IV had done nothing to reverse the slide. What was needed more urgently than ever was internal reform; only it could restore people’s faith in the Church’s moral right to be the captain of their souls. To his eternal credit, Pius recognized this and gave it more than lip service, reconvening the Council of Trent to take up the issue once again, this time with the full support of the papacy.

It reopened for business on January 18, 1562, with five cardinals, three patriarchs, eleven archbishops, ninety bishops, four generals, four abbots, and hundreds of ordinary priests and monks on-hand for what would prove the most important Church conclave since Antiquity. All now agreed that internal reform must be the order of the day; the only questions were what kinds of reforms, and how far to take them. Some proposals were truly radical, echoing some of the ideology of the Protestant Reformation. A French delegation suggested that services should henceforward be conducted entirely in the vernacular languages of the people instead of Latin, that priests should be allowed to marry again, and that places of worship should be stripped of all of their paintings and statues, which constituted an invitation to idolatry. But, following the lead of the dignitaries who had met in Trent twenty years before, the majority decided that Catholicism would never win out over Protestantism by imitating it, thereby abandoning more than 1000 years of its own traditions. The way forward was to cling tighter than ever to those traditions, whilst also — and this was the key part — making them a lived reality for clergy and laity alike rather than a public pantomime. Harsh rules must be put in place to punish clergymen who violated their oaths of chastity or broke their promises to God and his people in any other way; seminaries must redouble their efforts to train priests in the habits as well as the words of asceticism and piety; the rampant nepotism at all levels of the Church must be done away with. The Church, in short, must learn to police itself, not so much for errors in thought as under Paul IV as for errors in deed. Only by doing this could it begin to rebuild its moral authority among the people and retain its sway over those parts of Europe that were left to it. This steely-eyed self-reckoning, undertaken in the nick of time after all other gambits had failed, would become known as the Counter-Reformation.

In only a few areas did the Council of Trent give way to Protestant dogma. While it held fast to the principle that the abodes of the Church should be beautiful in a very real, very visual sense, it agreed that the flamboyant nudity depicted by artists like Michelangelo had become excessive. And in a supreme irony, it finally acknowledged publicly that the Church had been in the wrong all along on the subject of indulgences, the practice which had prompted Martin Luther to compose his 95 Theses in the first place. Indulgences, declared the council, were “a source of grievous abuse among the Christian people,” nothing less than a source of “criminal gain” for those monks, priests, and popes who had lived off them for centuries. The mea culpa came much, much too late to avoid the schism, but better late than never.

Its hard work accomplished in less than two years after two decades of shirking what really needed to be done, the Council of Trent adjourned for the last time on December 4, 1563, having altered the face and the course of Catholic Christianity forever.

That said, we mustn’t exaggerate the immediate impact of the Council of Trent and its Counter-Reformation. Corruption didn’t disappear at the stroke of a pen; as the Church’s 21st-century sexual-abuse scandals demonstrate all too clearly, bad apples and institutional failures to weed them out would remain an ongoing fact of life. Nevertheless, the Counter-Reformation signaled a permanent change of attitude, inculcating an earnest expectation that the men of the Church would live up to the letter of their oaths in place of a “boys will be boys” mentality. The most important reforms are, like the most important revolutions, the ones that take place in the head. Will Durant:

The Counter-Reformation succeeded in its principal purposes. Men continued, in Catholic as much as in Protestant countries, to lie and steal, seduce maidens and sell offices, kill and make war. But the morals of the clergy improved, and the wild freedom of Renaissance Italy was tamed to a decent conformity with the pretensions of mankind. Prostitution, which had been a major industry in Renaissance Rome and Venice, now hid its head, and chastity became fashionable.

The ecclesiastical reforms were real and permanent. The popes ended their nepotism. The administration of the Church became a model of efficiency and integrity. The dark confessional box was made obligatory; the priest was no longer tempted by the occasional beauty of his penitents. Indulgence peddlers disappeared. Instead of retreating before the advance of Protestantism or free thought, the Catholic clergy set out to recapture the mind of youth and the allegiance of power.

Most importantly of all, the Counter-Reformation succeeded in halting the slow bleed of territory to Protestantism. The Netherlands was already lost by the time its full impact was felt, but it would prove the last major region to slip away. The existential crisis faded, leaving behind a diminished Church, true, but a proud and even strong one within its orbit, looking eagerly toward millions of souls in the Americas and East Asia as replacements for the European ones which Martin Luther had stolen out from under its nose.

Michelangelo died at the age of 88 just two months after the Council of Trent finished its work. He was given a splendid funeral in Rome, presided over by Pope Pius IV himself. Then his body was removed to Florence, where a second, almost equally lavish funeral was held before its entombment. An inscription on his tomb called him “the greatest painter, sculptor, and architect that ever lived.” More than five and a half centuries later, it is difficult to argue the point, at least if we insist on judging those talents in the aggregate in one man. As I have so often before in these pages, I will leave the last word on this subject to the unfailingly eloquent Will Durant.

The last word must be one of humility. We middling mortals, even while presuming to sit in judgment upon the gods, must not fail to recognize their divinity. We need not be ashamed to worship heroes, if our sense of discrimination is not left outside their shrines. We honor Michelangelo because through a long and tortured life he continued to create, and produced in each main field a masterpiece. We see these works torn, so to speak, out of his flesh and blood, out of his mind and heart, leaving him for a time weakened with birth. We see them taking form through a thousand strokes of hammer and chisel, pencil and brush; one after another, like an immortal population, they take their place among the lasting shapes of beauty or significance. We cannot know what God is, nor understand a universe so mingled of apparent evil and good, of suffering and loveliness, destruction and sublimity; but in the presence of a mother tending her child, or of a genius giving order to chaos, meaning to matter, nobility to form or thought, we feel as close as we shall ever be to the life and mind and law that constitute the unintelligible intelligence of the world.

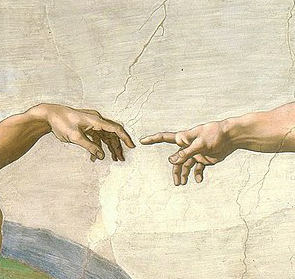

Michelangelo’s twin funerals marked not just the passing of a man but of an entire aesthetic in Catholic art. One month after his death, a team of workaday craftsmen whom he would doubtless have considered unworthy to clean his brushes entered the Sistine Chapel to paint clothing onto many of the nude figures on his altar wall, in accordance with the decree out of Trent that Catholic art must become less blatantly sensual, must appeal solely to the spirit in Heaven rather than the carnality of the Earth. Restorers have spent much time and effort in more recent years trying to undo the damage of these censors.

On the whole, though, Michelangelo’s posterity was lucky: even as the deceased artist was being venerated in public, many of the more zealous figures of the Counter-Reformation were lobbying hard to paint the altar wall over entirely, and possibly even the Sistine Chapel ceiling as well. For, as Miles J. Unger puts it, Michelangelo’s legacy had become “something of a problem” for the Church of the Counter-Reformation era: “the brightest star in a constellation of brilliant men whose talents had served to glorify the one true religion, but also a dangerous example of freethinking that was no longer acceptable in an age that valued discipline over originality.” Reform always comes at a price; praise be that the complete destruction of the Sistine Chapel’s adornments was not added to the bill in this case.

Michelangelo’s final and grandest project of all was still unfinished at the time of his death; the new Saint Peter’s Basilica was still in a woefully incomplete state. It remained an only intermittently ongoing project for many years after. Not until 1590 was the dome set in place, on a plan a very different from those of both its original architect Bramante and Michelangelo himself. For Italy was now entering the Baroque period of architecture, a heavily ornamental style that strove for sheer spectacle above all else, being designed in the spirit of the Counter-Reformation to appeal to the sensibilities of the masses rather than the intellectual elites. Michelangelo, being a proud member of said elite, would probably have loathed it.

Even after the dome was raised, even after the falling-down old Saint Peter’s Basilica was demolished once and for all in 1608, the construction effort crept along at a frustratingly slow pace. At last, on November 18, 1626, Pope Urban VIII consecrated the new first cathedral of Catholicism — the largest single building of worship in the world, then as it still is today, a monument and symbol which could and can be seen to magnificent effect from virtually any location in the city that housed it, as all of its various architects always intended it to be. It had space enough beneath its soaring vaults to swallow entire armies of pilgrims and still bid welcome to more.

All of which is to say that Rome began to look the part of an imperial capital again only after the Roman Catholic Church had lost its hold on a large swath of Western Europe. Rome’s population had swelled enormously by 1626, making it now the third largest city on the continent, a far cry from the slatternly shadow of the past that had greeted Michelangelo on his first visit. This is the Rome that is known to the tourists of today, the same ones who stream in to gawk at the Sistine Chapel amidst the other items on their bucket lists. Most of them imagine Saint Peter’s Basilica and the other physical trappings of the Eternal City that surround the cathedral to be much older than they really are.

But the fact is that the new Saint Peter’s Basilica and almost all of that which stands around it are products of a complicated Modern era, not of the Church’s period of unchallenged supremacy in Europe; they were built not with the tithes and indulgences of European peasants and nobility but with New World gold and silver, dug out of the ground using slave labor, that original sin of Europe’s colonies there. The Catholic Church more than succeeded in fending off the existential threat of Protestantism in the end, such that it is larger than ever today in purely numerical terms: almost 1.4 billion members, 20 percent and more of the world’s population, although only about 260 million of them are Europeans. Yet it is a humbler, soberer institution one finds when one penetrates beneath the outward show of grandeur, a Church which mostly stays out of the day-to-day vagaries of temporal politics, which certainly no longer mounts Crusades or wages wars in any but the most strictly metaphorical senses. Ever since the Counter-Reformation, it has expected rather more of itself and asked rather less of its parishioners. And this, it seems to me, has been all to the good.

The Sistine Chapel is still justifiably reckoned one of the Church’s most awe-inspiring treasures of all. But when we take a closer look — the kind of look that can lead to such a lengthily digressive book as this one — we find that it can do more than awe us with its beauty. Frozen permanently on the tide of a sea change in history, the ceiling looks backward to a time of absolutism and self-assurance, while the altar wall looks forward to a murky, ambiguous Modernity, a time with fewer easy answers but one that is perhaps ennobled by its simple willingness to permit the hard questions.

The Modern songwriter Frank Orrall once described standing before a painting in an American museum whose subject was the same as one of the frescoes on the chapel’s ceiling.

In it, Adam and Eve looked full of shame as they were banished from the beautiful garden into the dark unknown of the lower right hand corner of the canvas. This didn’t seem right to me. I felt that in that darkness is the beginning of life as I know it. The gift of sensuality, bliss, pain, exploration of self, strife and mortality — all give this life a poignancy, dimension, and depth that I don’t feel from any notion of Eden.

Something was lost when the Age of Faith passed into history, carrying with it the spiritual anchor of a single authoritative Church with a fixed conception of the universe and humanity’s place within it. Yet something even more precious was gained. For with the loss of certainty comes the beginning of a truer wisdom — not God-given, but scratched out of the soil of our messy, complicated, heartbreaking, joyous, ineffable, and oh-so human mortal existences. In this Age of Modernity, we can finally see ourselves — every last one of us — as the little gods we really are.

Did you enjoy this chapter? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

Leo Vellés

Congratulations Jimmy, an excellent epilogue to a superb series. Can’t wait for the next one. Can you give us a little synopsis of what is to come?

Jimmy Maher

The next article will come four weeks rather than two from this last one, and will start the series on Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage around the world. I’m looking forward to doing something a bit more embodied, even novelistic — a straight-up adventure story instead of another grand-sweep-of-history sort of thing.

Martin

Are there any pictures/diagrams of the state of St. Peter’s at the time of Michelangelo’s death?

Great series overall.

Jimmy Maher

Although I don’t believe it has anything like detailed plans, I can recommend Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces by Miles J. Unger as a very readable source of more information. The last of the six masterpieces is Saint Peter’s Basilica. 😉

Christian Studer

I agree, beautiful epilogue. And it was a fun series, didn’t see the whole reformation side quest coming. Thank you very much.

Tim K.

“…such that is larger than ever today in purely numerical terms” seems to be missing an “it”.

Now, with that out of the way…

Fantastic ending to a fascinating series! Although all of your Wonders of the World books have been a treat to read online, I would consider this one in particular to be worthy of a printed edition, in hardcover, professionally formatted and with full-color illustrations – if such a thing were logistically and economically feasible. After all, what could be a more appropriate treatment for a narrative in which the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press was one of the pivotal events?

I imagine some readers of a more traditionally religious stripe might judge your concluding paragraph to be an expression of humanistic hubris bordering on blasphemy. If so, they would do well to remember what the eighth Psalm — attributed, like so many biblical psalms, to King David — has to say about humanity: “For you [the Lord] have made him a little lower than the angels, and crowned him with glory and honor.” And just to drive the point further home, the World English Bible (the source of this translation) includes a footnote explaining that the Hebrew word Elohim, translated as “angels” here, “usually means ‘God,’ but can also mean ‘gods’, ‘princes’, or ‘angels’.” So there we are — “little gods” indeed!

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

I’m afraid it just isn’t practical to do a physical book to the standard I would expect at this time. But we can dream, right? 😉