A century before the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon, the Assyrian Empire was at the height of its power. Upon assuming the throne in 705 BC, the Assyrian King Sennacherib had moved his capital from Ashur to Nineveh, another, newer city in northern Mesopotamia. From here, he and his successors commanded the most feared legions to be found anywhere in the world, as famed for their discipline in battle as they were for their military technology. The very first people to fight with weapons and armor made primarily out of iron rather than bronze, they augmented this advantage with such innovations as the composite bow and all-weather hobnailed boots. Their contemporaries considered them to be well-nigh invincible in battle, and this was probably a fair assessment on the whole.

Indeed, the Assyrians’ fearsome reputation precedes them even today. “Assyria must surely have among the worst press notices of any state in history,” noted Paul Kriwaczek in his recent history of Mesopotamia. “Babylon may be a byname for corruption, decadence, and sin, but the Assyrians rate in the popular imagination just below Adolf Hitler and Genghis Khan for cruelty, violence, and sheer murderous savagery.” And then he goes on to quote the opening lines of Lord Byron’s poem “The Destruction of Sennacherib,” as one inevitably must when writing about the Assyrians:

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.

Byron’s poem draws from the Bible, where the Assyrians feature almost as prominently as antagonists as do the Babylonians. In approximately 720 BC, the Assyrian King Sargon II conquered Israel, one of two kingdoms into which the Hebrew people had splintered by that time. In 701 BC, his son Sennacherib returned to finish the job, besieging Jerusalem, the capital of Judah. But for some reason the Assyrians abandoned the siege; according to the Bible’s Book of Kings because God decided to “defend this city, for mine own sake, and for my servant David’s sake.” And so, to quote Byron once again, “The Angel of Death spread his wings on the blast, and breathed in the face of the foe as he passed.” Meanwhile Sennacherib’s own account in his royal annals says that the Hebrews merely offered to pay him so much tribute that he agreed to leave them alone.

Whatever really happened at Jerusalem, it was surely a rare example of the Assyrians allowing a foreign people to remain unconquered. At its height, the Assyrian Empire enveloped a huge swath of the Near East, of which the entirety of Mesopotamia was only the beginning. It constituted the largest empire in the history of the world to that time; even the entirety of Egypt fell under its sway. “Let them hate, so long as they obey,” was the Assyrian kings’ stated attitude toward the peoples they conquered. The inscriptions they left behind are often extraordinary for their gloating cruelty. Consider this one from Esarhaddon, the son of Sennacherib, describing what he did to the land of Elam and its capital of Susa, which lay some distance east of Mesopotamia.

Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed. I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur [the patron deity of the Assyrians]. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt.

So, it does seem that the Assyrians’ contemporaneous and modern reputation for extreme brutality was in some cases at least well-earned. The Assyrian Empire was, one might say, the prototypical Evil Empire.

But why, you may be wondering, are we suddenly so interested in the Assyrians instead of the Babylonians? The answer to that question begins with an artifact acquired under unknown circumstances in around AD 1840 by one Colonel R. Taylor, who was serving at the time as a British diplomat in Baghdad. It takes the form of a hexagonal prism, 15 inches (38 centimeters) high, its sides completely covered with cuneiform writing.

In 1855, the now-deceased Colonel’s widow sold this “Taylor prism” to the British Museum for £250, where it languished for decades. It wasn’t until 1927 that the first complete translation of its cuneiform was published, by the American Assyriologist Daniel David Luckenbill. He determined that it stemmed from the Nineveh of about 690 BC, during the reign of Sennacherib. It was a lengthy, boastful record of all of that king’s achievements to date, written, as was always the style among Mesopotamian kings, in the first person. Sennacherib’s roll call of accomplishments includes plenty of foreign military victories — among them his campaigns against the Hebrews — but also makes room for his domestic construction programs in his capital of Nineveh. One section of Luckenbill’s translation stands out as particularly interesting, appearing to describe a magnificent park and garden which he built around his palace. Although the translation is often uncertain, confused and confusing, we can gather that Sennacherib is positively crowing about the technological innovations that allowed him to carry out the work.

In times past, when the kings, my fathers, fashioned a bronze image in the likeness of their members, to set up in their temples, the labor on them exhausted every workman; in their ignorance and lack of knowledge, they drank oil, and wore sheepskins to carry on the work they wanted to do in the midst of their mountains. But, I, Sennacherib, first among the princes, wise in all craftsmanship, great pillars of bronze, colossal lions, open at the knees, which no king before my time had fashioned — through the clever understanding which the noble [god] Nin-igi-Kug had given me, (and) in my own wisdom, I pondered the matter of carrying out that task, following the advice of my head (will) and the prompting of my heart I fashioned the work of bronze and cunningly wrought it.

Over great posts and crossbars of wood, 12 fierce lion-colossi together with 12 mighty bull-colossi, complete in form, 22 cow-colossi clothed with exuberant strength and with abundance and splendor heaped upon them, — at the command of the god I built a form of clay and poured bronze into it, as in making half-shekel pieces, and finished their construction. Bull-colossi, made of bronze, two of which were coated with enamel (?), bull-colossi of alabaster, together with cow-colossi of limestone, I placed at the thresholds of my palaces. High pillars of bronze, together with tall pillars of cedars, the product of Mount Amanus, I inclosed in a sheathing of bronze and lead, placed them upon lion-colossi and set them up as posts to support their doors. Upon the alabaster cow-colossi as well as the cow-colossi made of bronze, which were coated with enamel (?) and the cow-colossi made of GU-AN-NA, whose forms were brilliant, I placed pillars of maple, cypress, cedar, dupranu-wood, pine and sindu-wood, with inlay of pasalli and silver, and set them up as columns in the rooms of my royal abode. Slabs of breccia and alabaster, and great slabs of limestone, I placed around their walls; I made them wonderful to behold. That daily there might be an abundant flow of water of the buckets, I had copper cables (?) and pails made and in place of the (mud-brick) pedestals (pillars) I set up great posts and crossbeams over the wells. Those palaces, all around the (large) palace, I beautified; to the astonishment of all nations, I raised aloft its head. The “Palace Without a Rival” I called its name.

There is much here to capture the attention of anyone on the hunt for Hanging Gardens, but scholars initially fixated on something else entirely. Luckenbill’s translation vexed them for years because of its use of “the making of half-shekel pieces” as a simile for the ease with which his technology allowed him to mold his statuary; it had long been believed that Mesopotamia never developed the concept of financial currency on its own, that coins wouldn’t come into use there until they were imported by Alexander the Great some 375 years after the accepted date of Taylor’s Prism. Yet there was no question of the text’s authenticity; two other, similar prisms from the same period containing exactly the same text had come to light by the time Luckenbill made his translation. Could this anachronistic allusion to coinage therefore be a failure of his translation?

Such was British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley’s strong suspicion when she stumbled across the text in the 1970s whilst researching a lecture on the invention of coinage. The word “shekel,” as she well knew, had represented a measure of weight, equal to about four-tenths of an ounce (11 grams), before it had been applied to currency. Returning to the original cuneiform text, she devised a new translation for the troublesome phrase in question by making use of some of the new linguistic knowledge that had been gained in her field in the last half-century: “I made the castings of them as perfectly as if they had only weighed half a shekel each.” Problem solved.

Dalley would later write that as a result of this experience she “became interested in problems of recognizing technical details in cuneiform texts, and in the use of similes and metaphors to describe innovations.” There was, she suspected, plenty more of that sort of thing going on in this very same text; she believed that Luckenbill’s complete translation was, while perhaps a good start, a woefully inadequate way to leave things. She looked hard at the places where Luckenbill himself had expressed his confusion in the form of parentheticals. For example, she concluded that his tentative “enamel” really should be “electrum.”

Other obviously confused passages, however, were less immediately amenable to clarification. She zeroed in on one sentence in particular: “That daily there might be an abundant flow of water of the buckets, I had copper cables (?) and pails made and in place of the (mud-brick) pedestals (pillars) I set up great posts and crossbeams over the wells.” What on earth to make of this? It made very little sense at all, in terms of hydrology or anything else. She felt that she just had to try to sort it out for herself.

She soon found that some of the work had already been done for her. In 1953, a Danish scholar named Jørgen Laessøe had proposed that Luckenbill’s “copper cables and pails” ought to read, “ropes, cables of bronze, and chains of bronze.” More importantly, he had made a persuasive argument that the word which Luckenbill had translated as “pedestals” or “pillars” really ought to be “shadoof.”

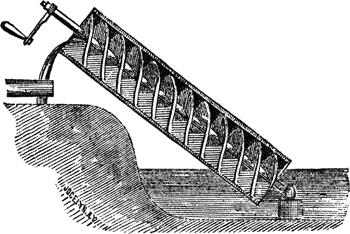

The shadoof is one of humanity’s oldest machines, being a mechanical method of raising water out of the ground. It was in use in Mesopotamia already by 3000 BC, and continues to be used in many parts of the world to this day. It looks much like a seesaw where the swiveling plank is affixed to the stationary base not at the plank’s center but rather as far as four-fifths of the way down its length. A bucket or other receptacle is mounted at the long end of the plank on a rope, a counterweight at the short end. The operator pulls down on the rope to lower the bucket into a well or other body of water; when he or she then releases the rope, the counterweight pulls the now-filled bucket back to the surface to be detached and carried away, or emptied into some other receptacle such as an irrigation canal.

Dalley found Laessøe’s alternative translation enticing indeed. It seemed that Sennacherib was bragging about having replaced the effective but labor-intensive technology of the shadoof with a more efficient method of raising water. Still, the translation remained manifestly flawed. Laessøe proposed that the full sentence in question must read, “Instead of shadoofs, I let beams and the date palm stand over the wells.” This still made no sense. How could one use “beams and the date palm” as a replacement for a shadoof?

By studying translations of cuneiform mathematical texts, Dalley discovered that the word which Luckenbill and Laessøe had variously translated as “posts” and “beams” could also mean a cylinder. This seemed highly promising, given the hydrological context. But she was still stuck with that odd reference to a date palm. The Akkadian word for same — “alamittu” when transcribed into Latin characters — had no other known meanings whatsoever.

So, she went to the Kew Botanical Gardens in London to take a careful look at the tree in question. And what she saw excited her. The surface of the trunk was formed into a distinct spiral pattern. Could this pattern be what the text was referring to, rather than a literal example of the tree itself? If so, it would be far from an unusual linguistic development in ancient times — or in our own. The names we apply to our technology have often been metaphors based on its resemblance to natural forms. For example, the Romans called the shields which their legions carried into battle “tortoises.” And today we speak of a railway line’s branch, of a rat-tail file, of a shoe tree, of a computer’s mouse, of a World Wide Web.

The combination of a cylinder and a spiral in the context of hydrology can lead to only one place: the screw pump, where a rotating, spiral-shaped screw mounted inside a hollow cylinder is used to raise water much more quickly and efficiently than can be accomplished with the likes of a shadoof. By tradition, the screw pump’s inventor was Archimedes, a Greek mathematician, engineer, and natural philosopher of the third century BC who first proposed using it to remove bilge water from large ships. (Ironically, the Greeks and Romans of the centuries after Archimedes gave his machine a name that was another example of a metaphor derived from the natural world: they referred to it as a “snail,” after the same helical shape of its central component that may have caused the Assyrians to label it a date palm.) But there were many clues embedded in the classical texts that the screw pump may in fact have predated Archimedes, that it was just one more example of the Greeks being given credit that they hadn’t quite earned. Seen in this light, Archimedes may have been the first to apply the concept to sea travel — the screw pump remains a staple aboard ships to this day — but not the first to develop it in the abstract. Diodorus, for one, explicitly stated that Archimedes “found” the screw pump “when he was going round in Egypt.” And, indeed, some modern historians of technology now believe that its use there may date back to hundreds of years before Archimedes’s “invention” of it.

Given this, and given the considerable degree of cross-cultural dialog that took place between Mesopotamia and Egypt, it struck Stephanie Dalley as very possible that the screw pump had made its way from the latter to the former already by the time Sennacherib built his palace complex in approximately 700 BC. For that matter, it was by no means inconceivable that the screw pump had been invented in Mesopotamia and later made its way to Egypt. Certainly Sennacherib’s boast that he used it instead of a humble shadoof would seem to imply that the screw pump was a cutting-edge technology in his day and age.

Of course, Dalley’s process of deduction was not really so straightforward as the outline I’ve provided here. It took her decades after stumbling across the text on the Taylor Prism to cover the ground we’ve managed in a handful of paragraphs; it cannot be emphasized enough that cuneiform writing is damnably complex, its deciphering as much art as science (or vice versa). Some of Dalley’s blind alleys wound up consuming years of her time. But by 2013, when she published a book describing her research in its entirety, she was prepared to offer a much-improved if not definitive translation of the text which we’ve already seen in Luckenbill’s version. In addition to reading much more clearly in general, it’s notably longer and more detailed, thanks to Dalley’s stubborn determination to persevere with gnarly passages that had evidently caused Luckenbill to throw up his hands and skip over them.

Whereas in former times the kings my forefathers had created copper statues imitating real forms, to put on display inside temples, and in their method of work they had exhausted all the craftsmen for lack of skill and failure to understand principles (?); they needed so much oil, wax and tallow for the work that they caused a shortage in their own lands — I Sennacherib, leader of all princes, knowledgeable in all kinds of work, took much advice and deep thought over doing that work. Great pillars of copper, colossal striding lions, such as no previous king had ever constructed before me, with the technical skill that Ninshiku brought to perfection in me, and at the prompting of my intelligence and desire of my heart I invented a new technique for copper and made it skillfully. I created clay moulds as if by divine intelligence for cylinders and screws, tree of riches; twelve fierce lion-colossi together with twelve mighty bull-colossi which were perfect castings; 22 cow-colossi with joyous allure, plentifully endowed with sexual attraction; and I poured copper into them over and over again; I made the castings of them as perfectly as if they had only weighed half a shekel each. Two of the copper bull-colossi were then coated with electrum. I installed alabaster bull-colossi alongside white limestone bull- and cow-colossi at the door-bolts of my royal pavilions. I bound tall pillars of copper alongside pillars of mighty cedar, the gift of the Amanus mountains, with bands of copper and tin, and stood them on lion bases, and then positioned door-leaves to crown their gateways. I positioned alabaster cow-colossi cast in copper coated with electrum, and cow-colossi cast with tin, to make very shiny surfaces, also pillars of ebony, cypress, cedar, juniper, pine and Indian wood, inlaid with gold and silver, on top of them, and positioned them in the dwelling-place, my seat of government, as door-posts for them. Threshold stones of brecchia and alabaster, and threshold stones that were large blocks of limestone, I put around their footings, and I have made a wonder of them.

In order to draw water up all day long I had ropes, bronze wires and bronze chains made, and instead of a shaduf I set up the great cylinders and alamittu-screws over cisterns. I made these royal pavilions look just right. I raised the height of the surroundings of the palace to be a wonder for all peoples. I gave it the name “Incomparable Palace.” A part imitating the Amanus mountains I laid out next to it, with all kinds of aromatic plants, orchard fruit trees, trees that sustain the mountains and Chaldaea, as well as trees that bear wool, planted within it.

I trust that the implications of Stephanie Dalley’s dogged research are now becoming clear. The second paragraph above is exactly the sort of primary-source evidence for the Hanging Gardens which historians have looked for in vain among the many cuneiform tablets and inscriptions recovered from Babylon. Should we have been talking about a Hanging Gardens of Nineveh rather than a Hanging Gardens of Babylon all along? Dalley, for one, believes strongly that we should have.

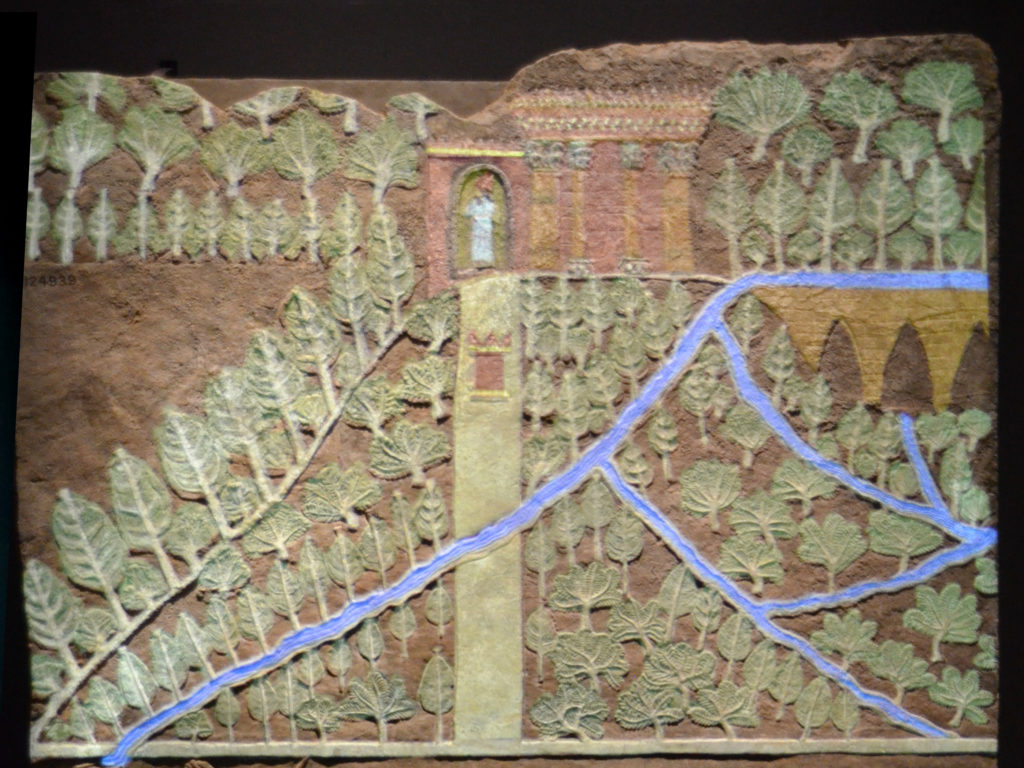

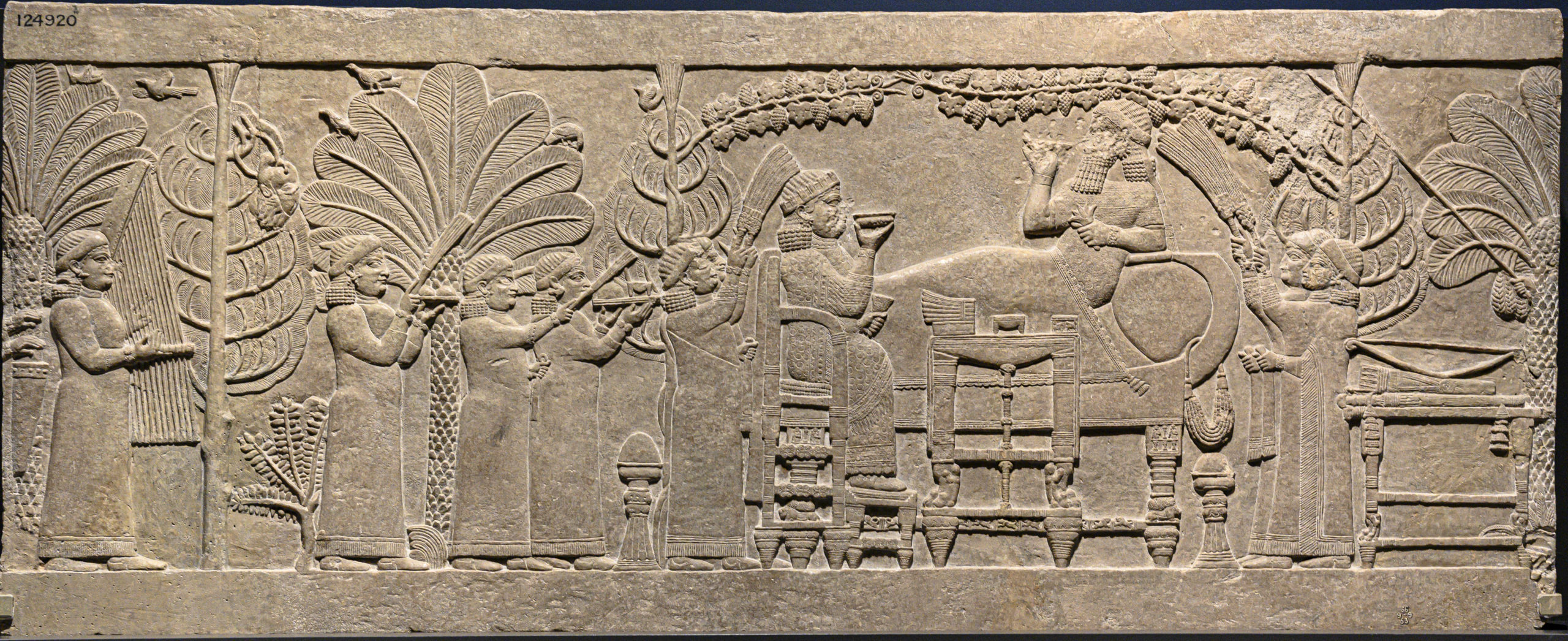

To bolster her case, she supplements the translation above with an impressive amount of other, circumstantial evidence. She notes that, for all their apparent delight in brutal war, the Assyrians were hardly barbarian primitives. Indeed, their prowess in battle was a direct result of their technological sophistication; in addition to being natural warriors, they were natural builders and engineers, not least in the field of hydrology. Nineveh stood on the bank of the Tigris River, but that river at this northern location is a somewhat erratic source of drinking water; melting snow in the mountains causes the river to run high in the spring and early summer, stirring up sediment from its bottom that is unpleasant at best to ingest. Therefore Sennacherib and other Assyrian kings built one of the most elaborate canal systems of the ancient world in order to bring copious quantities of clean, pure water down from the mountains to the north of Nineveh. Enormous bas-reliefs that were carved to celebrate their waterworks still exist in several remote locations. And truly they were something worth celebrating, coming complete with dams, reservoirs, and sluice gates to regulate the water’s flow, even raised aqueducts to let one stream pass over another. Clearly the Assyrians had become masters of hydraulic engineering by the time of King Sennacherib — much more so than the Babylonians. If any Mesopotamian people was capable of raising enough water up to the heavens to feed a spectacular elevated garden, it would seemingly be them.

Further, while both the Babylonians and the Assyrians had a great love of gardens in general, their approaches to their gardens’ layouts were quite different: the former tended to take a workmanlike attitude, all square grids laid out on flat land, while the latter were more audacious. “Assyrian gardens in the north,” writes Dalley, “were created in or near cities with far more energetic designs, expressly to imitate mountain landscapes, by heaping up artificial hills, by planting fragrant mountain trees on their slopes, and by engineering running water to cool the air, keep the herbage green, and provide the soothing sound of rippling streams.” A Hanging Gardens of Babylon, in other words, would be an exception to the rule of Babylonian gardening; a Hanging Gardens of Nineveh would be very much in harmony with what we already know of the Assyrian approach, albeit on an unusually awesome scale.

And there are some other pieces of tantalizing physical evidence for a Hanging Gardens of Nineveh to augment the text of the Taylor Prism. A collection of intricate bas-relief carvings depicting gardens — some of them appearing to be elevated, even seeming to correspond with some of the descriptions of the Hanging Gardens by the ancient writers — was found inside the palace of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh during the nineteenth century of our epoch. (In fact, I must now confess that one of these bas-reliefs serves as this series’s cover art rather than an image from Babylon proper.) Ashurbanipal was the very last of the great Assyrian kings, reigning from 669 to 631 BC. Thus these carvings presumably depict the city of Nineveh at its absolute peak of development, including all of the preserved works of Ashurbanipal’s predecessors. Were the Hanging Gardens of Nineveh among them? It’s wonderfully tempting to think so.

One final tantalizing data point involves the oft-repeated ancient claim that the Hanging Gardens were built for a king’s favorite queen. Nothing has been found in Babylon to substantiate this claim. But the following inscription has been found in Nineveh and attributed to Sennacherib:

And for Tashmetu-sharrat the palace woman, my beloved wife, whose features the Mistress of the Gods has made perfect above all other women, I had a palace of loveliness, delight and joy built, and I set female sphinxes of white limestone in its doorways. At the command of Ashur, Father of the Gods, and of Ishtar the Queen, may we be granted days of health and happiness together within these palaces, may we have our fill of well-being, may the favourable protecting deities turn to these palaces and never leave them.

The inscription makes no explicit mention of a garden, hanging or otherwise, but it isn’t hard to imagine one that is part of a grand palace complex dedicated to this most beautiful and lucky of all queens.

Herodotus and other sources tell us that Nineveh was conquered and utterly destroyed in 612 BC by a coalition of the peoples whom the Assyrians had previously dominated; unlike Babylon and the many other Mesopotamian cities about which such extravagant claims of complete annihilation were made, Nineveh would never rise again to become more than a provincial village. This, then, provides an explanation for Herodotus’s conspicuous failure to see any Hanging Gardens when he apparently traveled through Mesopotamia a century and a half after the destruction of Nineveh, on the hunt for just such wondrous things.

After analyzing carefully the same ancient descriptions of the Hanging Gardens which we examined in Chapter 3 and comparing them to maps of the ruins of Nineveh, Dalley has even found what she believes to be the most likely location of them there, at a plum spot overlooking the Tigris River and the landscape beyond. (Archaeologists are sadly unable to do much physical investigation there today because of the ongoing chaos in that part of the world; the ruins of Nineveh stand near the tortured modern city of Mosul, a full-fledged war zone until 2017 that is still plagued with unrest and terrorism.)

So, Dalley postulates that the ancient writers simply mistook Nineveh for Babylon. This assertion may appear far-fetched on the face of it, but becomes at least modestly less so when one drills down into the details. There is, first of all, the sheer remoteness of either city from the centers of Greek and Roman civilization.

And then there is the fact that the ancients in these other parts of the world really did make a well-documented habit of confusing the two cities. One of the most amusing examples, from a source that seemingly should have known better, is the Catholic Bible’s Book of Judith (it can also be found amongst the Apocrypha of the Hebrew and Protestant Bibles). A work of unknown date and provenance, it tells the story of a beautiful and brave Jewish widow who saves her people from destruction by beguiling an Assyrian general — or is he meant to be a Babylonian general? The opening line doesn’t do much to clarify matters: “In the twelfth year of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, who reigned in Nineveh, the great city…”

Herodotus appears at times to be equally confused. At one point, he launches into a lengthy digression about the waterworks supposedly constructed by a mythical queen of Babylon, telling how she dug channels to bring more water into the city and employed ingenious methods to slow and otherwise control its flow. His description matches with nothing else in the historical or archaeological record of the Babylon we know, nor with the natural geography of its surroundings — but it does match up with the waterworks whose remnants can still be seen in the northern Mesopotamia of today. Herodotus even mentions that the canals flowed through an Assyrian village.

Should we then rewrite our history books to speak of the Hanging Gardens of Nineveh, as some credulous online resources have already begun to do? I must say that I, for one, am not quite ready to make that leap yet. For all the depth and breadth of her decades of research, Stephanie Dalley’s work betrays some conspicuous weaknesses. It is, to state the obvious, an awfully long chain of supposition and inference she’s assembled, with precious little incontrovertible proof. Like Robert Koldewey did before her, like all of us tend to do when we desperately want the assurance of black-or-white clarity, she tends to cherry-pick the evidence that bolsters her claim while rejecting the evidence that doesn’t.

Nowhere is this more prevalent than in her application of the ancient Greek and Latin texts. As we’ve already seen, Dalley claims that all of the writers of same placed the Hanging Gardens in the wrong city entirely. An error as fundamental as this one ought to cause one to regard every other aspect of the text in question with, to say the least, considerable skepticism. Yet Dalley relies heavily upon the nitty-gritty details of these same texts for her argument, as when she compares the bas-reliefs in the palace of Ashurbanipal with the ancient writers’ descriptions. Likewise, she identifies what she believes to be the location of the Hanging Gardens in the ruins of Nineveh in part by taking the dimensions of her plot of land from those mentioned by Diodorus and Strabo. But does she really have any reason to trust such granular details in texts that don’t manage to get the name of the city itself that houses the Hanging Gardens correct?

In the end, we can say that Dalley offers a compelling argument that a hanging gardens very probably existed in Nineveh at one time. She fails, however, to prove that this hanging gardens is the misnamed Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Who is to say that, given the perpetual rivalry between northern and southern Mesopotamia, a later Babylonian king such as Nebuchadnezzar II didn’t make his own gardens with the purpose of showing up the Assyrians? Who is to say that he didn’t import expert talent from the north to make this happen? Dalley bases some of her argument on the way that the notion of a hanging gardens dovetails with an established tradition of Assyrian gardening. Given this, why should the ones in Nineveh be the only examples of their type, in northern Mesopotamia or possibly even elsewhere?

These blind spots do not make Stephanie Dalley a bad scholar, still less a bad person; they simply make her human. We often wish to equate the process of sifting through the detritus of the past with science; we like to believe that there are incontrovertible truths and objective realities in history that can be uncovered and proven via something akin to the scientific method. But history — especially ancient history, where far more has been lost to us than has been preserved — doesn’t actually work that way. One can always hope to turn up more evidence, and sometimes one succeeds. But even after doing so, one never seems to have quite enough of it. And so judgment calls and, yes, sometimes the personal beliefs and desires of the historian come into play. For history is not science; it offers no experiments which we can run over and over until we’re satisfied we have arrived at an established empirical Truth.

By way of an example of the difficulties that face those who seek to understand the distant past through its shabby leavings, I’d like to return now to the place where we began this investigation: to Philo of Byzantium and his explication of the Seven Wonders of the World, the oldest text of its type to have come down to us. Or is it?

Already in 1875, the German philologist Hermann von Rohden raised doubts about whether the text in question really came from the pen that scholars thought it did. He noted that the linguistic construction of the Greek text didn’t jibe with its traditional dating to the third century BC. Most notably, it meticulously avoids the hiatus — the ending of one word with a vowel followed by the beginning of the next one with a vowel, a construction that was common in earlier times but was regarded as extremely bad style by writers of the twilight of the classical age. Based on this and other clues, von Rohden believed the text could stem from as late as the sixth century AD. Some scholars have subsequently connected it to a different Philo than the one who lived in the third century BC: a much more obscure Philo, confusingly also from Byzantium, who is believed to have lived and written in the fourth or fifth century AD. Stephanie Dalley, for the record, is among these advocates for a text more than half a millennium younger than the conventional wisdom has had it.

And yet the matter remains far from settled — and, indeed, will most probably never be settled. The principal argument against the later dating sounds a bit mushy and subjective in contrast to the hard linguistic reasoning applied by von Rohden, but is perhaps no less telling for all that. Simply put, the text doesn’t read like such a late specimen in any sense other than its linguistic construction. There is none of the jaded world-weariness that had begun to mark the declining Roman Empire by that point, no lip service paid to the Christianity that had become more dominant than ever there following Emperor Constantine’s conversion; it reads very much like a pagan document. All of these Seven Wonders of the Worlds were either already destroyed or in severe decline by the time this later Philo lived, yet the text makes no mention of this, treating them all as if they are still at the height of their glory. Sheer distance may do much to explain away the case of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which, if they ever existed in that place at all, were almost certainly long gone by the fourth century AD. But what of the other Wonders that were so much closer to home? What, for that matter, of the potential Wonders that stemmed from the last half-millennium, such as the Colosseum in Rome? Why neglect them in favor of all these ghosts of the past?

It seems to me that an equally plausible explanation for the linguistic irregularities in the text is that it was rewritten in late antiquity by some earnest scribe in order to bring it up to date and free its readers from the pain of its stylistic decrepitude, much as modern editions of Shakespeare update the Bard’s spelling and punctuation in order to make him more accessible. But this is only a guess. Perhaps this later Philo was simply wallowing in nostalgia for a better past, or indulging in some other form of poetic exercise whose context has been lost to us. There are no certainties on offer — which means that some scholars will continue to make the blanket statement that the text has traditionally been mis-attributed, even as others base entire books around the vision of a Philo writing about the Seven Wonders of the World in the third century BC.

After all this, then, we are left to ask ourselves once again what we really, truly know about the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. And we find that the answer remains a postmodernist’s dream: we know virtually nothing at all. All we have are rumors, legends, insinuations, speculations, and wishful flights of fancy. The harder we look for them, the more we learn that the Hanging Gardens are a shade, a breath of smoke that slips through our fingers and floats away every time we feel that we are about to grasp it firmly at last.

“It seems that the Hanging Gardens were conjured entirely from words,” writes John Romer, a British historian of ancient history. Slippery words of often unknown origin, words which will never hold still and just tell us that which we wish to know. Such is indeed the stuff of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. It’s entirely reasonable to feel frustrated over this, entirely understandable that brilliant thinkers like Robert Koldewey and Stephanie Dalley may have been tempted into outrunning the available evidence in order just to have an answer already.

At the same time, though, would we really be better off knowing the answer? Do we really need the Hanging Gardens to become one more plebeian data point in our data-driven existences? Or might it be okay just to let them continue to hang in our collective imagination instead, with all of their delicious temptation and aromatic beauty intact? The Hanging Gardens of Babylon have always existed in a place beyond archaeology, beyond history, and all of our attempts to bring them down to earth to date have done nothing to change that. Long may they bloom in the rarefied atmosphere of myth.

(A full listing of print and online sources used will follow the final article in this series.)

The Pachyderminator

Thanks for this shorter but equally fascinating series!

Typo:

if they ever existed in that place at all, were almost certainly long gone by the fourth millennium AD

presumably should be fourth century, not millennium.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

David Boddie

Nicely written and intriguing to read! Maybe one day we’ll get a more complete picture of the gardens’ place in history. There’s no rush: the journey is sometimes more enjoyable than the destination.

A couple of things to fix:

“gardens in generals”

“von Rhoden”

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Mike Russo

Loving the Wonders series so far. Even though not a lot of comments I think a lot of people are reading them. Your mention of Ashurbanipal reminded me of a great song, I’ll just leave this here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAMRTGv82Zo

Peter Olausson

Great reading, as always!

I must have missed the Assyrian reputation for cruelty, violence, and savagery. Is their rep in popular imagination even worse than that of the Huns and the Vandals? (Whether they deserve such a rating is another question, of course.)

Michael Waddell

This is fantastic. I’m sorry that this series has to end, but what a great ending! I will deeply miss your insightful and moving narrative essays about ancient history and historiography.

As an amateur Biblical scholar, I can relate deeply to your last three paragraphs. How much can archeology or the historic record really tell us about David’s Kingdom, or the Exodus (if such a thing happened), or even Jesus the Galilean? So much less than we’d like, and in some cases, practically nothing. But in the end, it isn’t the historic record that has inspired so many for millennia; it’s the stories themselves. Reducing these stories to bare historical recountings can rob them of their symbolic meaning and their beauty. What we have is wondrous enough, and I can see how that’s true for a secular Wonder like the Hanging Garden as well.

Will Moczarski

we feel we feel that we are about to grasp it firmly

-> we feel that …

Jimmy Maher

Thanks!

Will Moczarski

I’m very happy that for now you’ll keep writing these brilliant series, Jimmy! Just out of curiosity: how much revenue would be necessary on Patreon for this to be sustainable? Maybe some of us regular readers would be willing to spread the word more, and possible future patrons should have the information (here or on your other website) that it’s possible for this to stop anytime barring more support. I’m sure that many aren’t aware about that at all. I know about (and can relate to) your discomfort concerning self-promotion but that fact at least should be out there.

Jimmy Maher

I’m very reluctant to put hard numbers on things, especially because I know that a fair number of Digital Antiquarian patrons consider their pledge to cover this site as well. (Although that perhaps makes my calculations more difficult, I totally understand why folks would prefer to sign up for one Patreon rather than two…) Nor do I like the idea of threatening to pack up my toys and go home if people don’t pledge their support.

But I would of course appreciate it if anyone who happens to read this comment and enjoys these series would tell anyone you know who might also happen to be interested in this material about this site and/or the ebook line. In my experience, word of mouth is still the way that the most lasting and worthwhile Internet projects get built.

William Rave

“Perhaps this later Philo was indulging in some form of poetic exercise whose context has been lost to us, wallowing in nostalgia for a better past.”

Perhaps I simply have a suspicious mind, but where my mind goes is “antique forgery”. I’m sure people were willing to pay good money for old stuff back then just like they do now.

Sam

Truly fantastic series! Thank you so much for putting this together in such a comprehensive and accessible way.

Since you seem to be crowdsourcing your edits, I should point out that “dedicated to this most beautiful and luckiest of all queens” should read “lucky” since there’s no such thing as “most luckiest” 😛 Another alternative would be “luckiest and most beautiful…”

As to the text, the first thing that caught my eye w/r/t the Taylor prism was all the mention of reducing the use of wax. In Ancient times in the Near East, there were only two sources of wax – bees and tallow (rendered animal fat). Clearly, these are expensive to produce, especially in mass quantities. So NB2 bragging about reducing wax usage is rather significant as it refers to making all those gigantic metal casts of animal-colossi.

Long before Ninevah, folks in the Middle East had mastered the art of “lost-wax” casting, which is still in use today. In a nutshell, it refers to making molds from wax and then pouring the molten metal inside in order to make “cast” items. Certainly, a gigantic copper/bronze cast of a cow would’ve used quite a lot of wax, indeed. So how was NB2 reducing the use of wax? My guess is that his colossi were hollow instead of being solid. This would’ve saved on materials AS WELL AS making the cast objects far, far lighter in weight, which could explain the whole “as light as a half-shekel” commentary (as well as how he hoisted them on top of such tall pillars). Although how he or his engineers discovered how to make hollow colossi is not mentioned in either translation of the Prism.

The Assyrians were definitely the masters of metalworking in the Near East. I have no idea if they discovered or invented an Archimedes’ screw, but I do know that (in modern times) it is possible to make a Screw out of copper. So that part is entirely plausible.

The “Amanus” Mountains referred to by NB2 are now known as the Nur Mountains in southwest Turkey. It’s clear from this reference that NB2 is bragging about his wealth and trading reach, as importing cedar from that distance was quite an achievement. Likewise, all the references to tin (almost exclusively sourced from Cornwall) is another way of saying he’s rich and can import stuff from really far away.

Iron is one of the most abundant elements on the planet, so getting your hands on iron (ore) is easy. The reason why the Assyrians were the first to master making items from iron, though, has to do with melting temperatures. Simply put, no matter how big you build a bonfire, it will never be hot enough to melt most metals. Therefore, the advent of the Bronze Age literally started because folks figured out how to build a hot enough fire to (s)melt copper and tin together. Iron, however, needs a “next level” kiln or forge to get to the requisite 1,500 degrees Celsius(!), so the Assyrians were clearly superb engineers, especially as it is very hard (and dangerous as heck) to turn that molten iron into something useful without killing yourself or burning down the city.

Contrast that with tin, (melting point 291 C) which I’ve seen smelted with my own eyes by regular folks on a hillside in England using nothing but a carefully constructed “kiln” made with stones and wood, used just once for the occasion and then discarded, hence Cornwall’s ability to ship pure ingots of tin with ease.

What with the Assyrians’ canal works, their advances in casting large metal statues, controlled production of iron weapons and other items, and access to materials like tin and bitumen (for waterproofing) as well as their possible invention of the Archimedes’ screw, it certainly seems reasonable to me that they had the engineering know-how to water and maintain a rooftop garden big enough to sustain trees (as opposed to small plants) that did not crush or destroy the building underneath, as well as allow for drainage. Whether or not they did so, and if it is the same as/similar to the famous “Hanging Gardens” of Babylon is unknown, of course, but it is a fascinating alternative explanation.

Going back to the Bible, it is interesting that in the OT account of Daniel and NB, there is a reference to iron statues, although it’s actually “mixed iron and clay” used as a metaphor for spiritual/religious purity. But it might also be a reference to someone struggling to smelt iron ore and remove its impurities, as that is quite difficult to do even if you can build a forge hot enough.

In addition, the famous story of the three kids (Shadrach, et al) in the same Book of Daniel involves people who entered a room with extremely high temperatures (and fire) and survived. Could this be an allegory to the Assyrians and their ability to smelt and cast iron? In other words, were Shadrach and Abednego et al inside an Assyrian ironworks foundry? Might be.

That being said, there are clearly anachronistic mentions of iron in the OT, including in Deuteronomy where they talk about an “iron-smelting furnace” in Egypt when the Egyptians most definitely did not have anything of the sort.

Lastly, it is believed that the fantastical “King David” (retconned by the authors of the OT, who were themselves the survivors of the two tribes that the Assyrians did NOT destroy through warfare or assimilation) took Jerusalem from the Jebusites during a siege. The new occupants then dug a rather impressive tunnel (which was recently discovered) to a water source precisely so THEY would not be vulnerable to a future siege by someone else. We’ll never know what happened during the later Assyrian attack, of course, but it makes sense that the folks in Jerusalem simply outwaited the siege thanks to their secret water source. In the entirety of the European Middle Ages, I don’t believe there was ever a successful siege of a castle/fortress that didn’t rely on either a) someone on the inside opening the gates or b) poisoning or cutting off the castle’s water supply.

I do believe that Ninevah has a lot more secrets to reveal, perhaps one day when Iraq is a more peaceful place. God knows that if someone finds some old copper parts to an Archimedes screw, that will be really exciting!

Thank you again for this wonderful series and to Stephanie Dalley for all of her hard work.

Jimmy Maher

Thanks for the edit, and thanks so much for all of your comments. I have little substantive to add to them — I shot my bolt, one might say, in the chapters proper — but I found all of them very interesting and informative. I really appreciate you taking the time to write them up in order to deepen every reader’s understanding, not least my own.

Krsto

Dear Mr. Maher, I cannot express well enough how much I’m enjoying in reading both of your blogs. In Analog I’m a bit of a latecomer and going through chronologically so this comment is probably not very actual, but I did found one typo to report (one instance of “Dally” instead of “Dalley”). Anyway, keep up this excellent work on both fronts, and I’m wondering is it possible to make single donations for your cause, and which is the best way to do it?

Jimmy Maher

Thanks for the correction! They are always relevant. 😉

The easiest way to make a one-time donation is through PayPal. You’ll find a link on this site on the right-hand side, just above the ebook links and the table of contents. Thanks for that as well!